Reclaiming Pocahontas Island: Part II

Maat Free figured out how to get Pocahontas on the Preservation Virginia’s list of the state’s most endangered historic places. Here’s what she said that made the powers that be take notice.

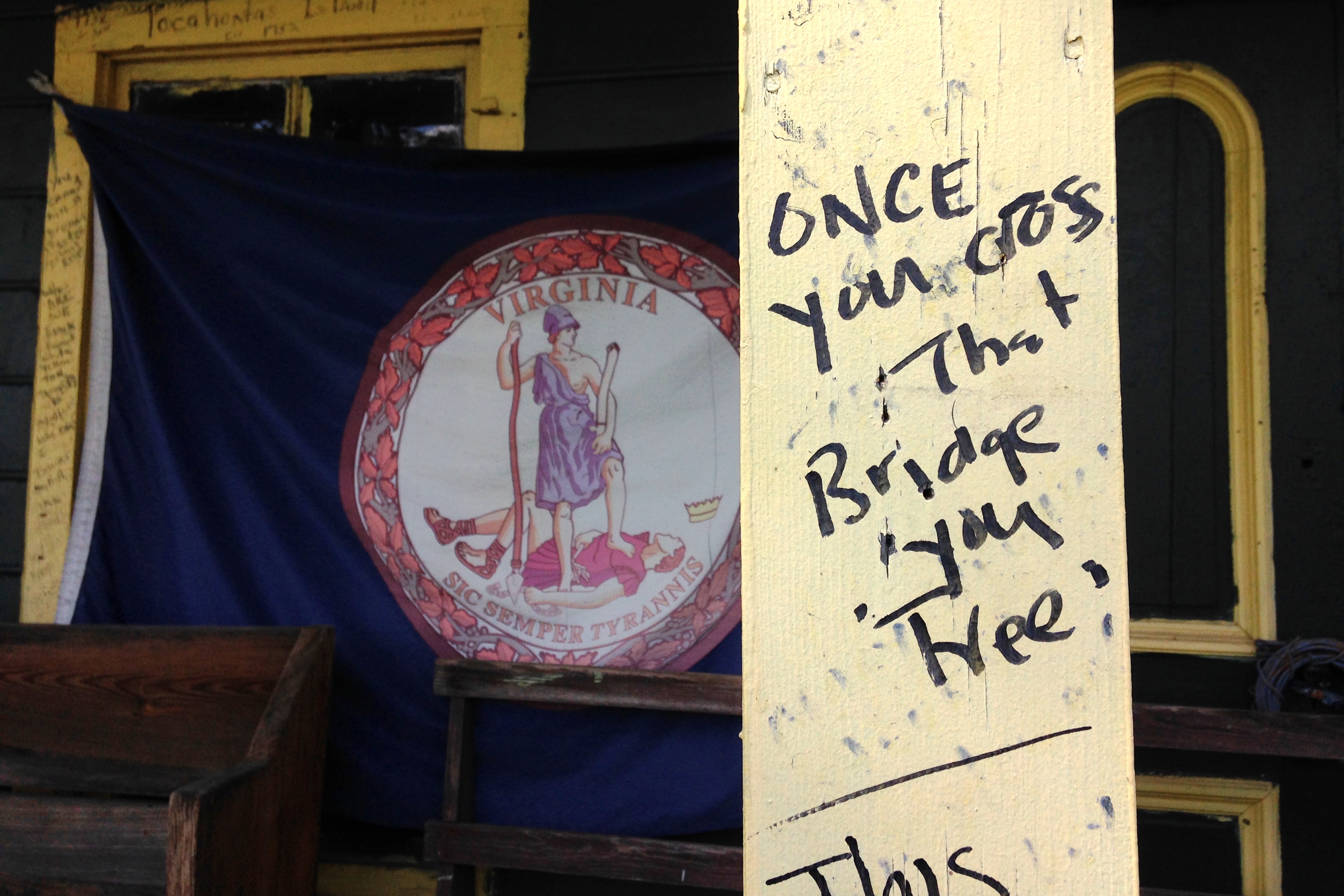

In June, I wrote a feature about a little island in the middle of the Appomaattox, only five minute’s walk from Old Towne Petersburg–an island that goes largely unnoticed by the hundreds of thousands of people who drive their cars right over it on I-95. This island, which doesn’t actually feel like an island, is in fact the site of the oldest community of free Black people in the United States.

I have traced my triple great-grandparents to the island, on the exact spot they moved to at the end of the CIvil War. Most important to this story, in my opinion, is that countless people were escaping from here to the North during the dark days of enslavement. That’s right, Pocahontas Island is home to at least two verified spots on the Underground Railroad.

In 2014, I wrote a nomination to historically preserve those portals to freedom. Below, you will find the actual Q&A on the nomination form I submitted. As a result of my independent research and advocacy, Pocahontas Island made it to the top of Preservation Virginia’s 2014 Endangered Site List.

You’re about to read what their selection committee read last year. The history of the island was compelling enough to kick off a major movement to properly honor the brave accomplishments of the people who lived at this place and rekindle the efforts of the current residents and keepers of Pocahontas Island history. Check it out…

— ∮∮∮ —

Please describe your site, including its current use and condition and existing zoning or other protective regulations, if any.

808-810 Logan Street is better known as the Jarrett House, after the free Black family who commissioned it to be built prior to the Civil War in either 1818 or 1820. It’s the oldest structure on the island. It is a double house with two front doors, two chimneys and constructed of handmade bricks. There are places where additions to the house can be seen, although they don’t exist anymore. The City of Petersburg has installed protective joists to support the bricks so that the structure does not collapse.

213-215 Witten Street, also known as the Underground Railroad House, is also in a state of disrepair. It is the only other pre-Civil War dwelling on the island. An exact date for its construction is not known, but the earliest mention is in 1838. It is one story and a half with two symmetrical sides, known in early architecture as a double house. There is a space for where a brick smokestack would have been right in the middle of the roof line. There used to be two front doors on either side, but right now, one is covered in the same Brick-Tex siding that wraps the rest of the house. It also used to have a porch for each unit but currently there’s one wide porch going across there from end to end. There’s also a shed in the back and a roof that extends from it to the house. Those Brick-Tex panels were added some time ago. The private owner began some efforts to renovate, but living in Maryland and being of advanced age kept her from being able to properly oversee the project, and it eventually became impossible to manage.

What is the historic significance of your site? (Has it been honored with a national, State, or local historic designation?)

Because the focus of my nomination is on the houses that were used as stations on the Underground Railroad, the historic significance of that freedom network takes center stage. The tri-cities area does not have a very well documented history concerning the path enslaved Africans took to acquire their freedom. In Richmond, we have the legendary narrative of Henry “Box” Brown, but almost no one knows about all the self-liberated Black people who made it out of bondage through the waterways surrounding Pocahontas Island.

In its current state, Pocahontas Island is little known to be the oldest Black community in the United States. There is a sign erected on the island that proudly declares this fact, and it makes for a fascinating narrative for this region. It was initially given to the grandson of the legendary princess Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Powhatan. Over time, free blacks settled here, especially during the early to mid 1800s. It was a thriving economic center because of its position in the middle of the Appomattox and provided jobs for the residents to work on the docks among all the cargo vessels travelling up and down the river. Pocahontas Island was a prosperous community for generations until the railways made river commerce obsolete. By the Depression era, the vast majority of its residents began to move North in search of employment. In 2006, the National Parks Service designated the whole parcel known as Pocahontas Island Historic District to be recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. I find it to be unfortunate that the assessors limited Pocahontas Island to be known as a site of local importance instead of the other two options which could have promoted it as a state or national asset. In their report, NPS concluded that the island is significant because of its Black ethnic heritage, aboriginal/non-aboriginal archaeology and architecture.

What is your site’s history? (Has its role in your community changed over time?)

My nomination is specifically for Pocahontas Island to be recognized as having two verifiable stops on the Underground Railroad, a fact that is extremely rare for Central Virginia. In the antebellum period, Black people would flock to Pocahontas on a mission to abscond from enslavement. They would hide in safe houses while waiting to embark on their perilous journey as stowaways in the engine compartment of a river boat to heading North towards freedom. The banks of the Appomattox became the last point of bondage that many people would ever see before they liberated themselves and began new lives above the Mason-Dixon.

In 1858, a commercial grade schooner called the Keziah was embroiled in a huge scandal involving a White ship owner named Captain William Bayliss (also known as Captain B.). He had just been caught with five Black enslaved individuals hiding on board his vessel, which was headed to Philadelphia. The stowaways had been hiding out in the Underground Railroad house at 213-215 Witten Street on Pocahontas Island before they had been discovered missing. The whole situation received an enormous amount of press coverage locally, throughout the state and all over the nation. The papers called the Keziah Affair “a breakdown on the Underground Railroad.” It was being reported that Captain B. had been liberating enslaved Africans for several years, charging them a fee to ride in the hull or engine of his ship. For him, this was a thriving enterprise but for enslaved Africans that had been able to make it to Pocahontas Island, this was their chance to get free.

Why do you want to save it? (What is special about it, and why does it continue to be important to you and your community?)

If these sites are preserved and opened to the public, a new narrative can emerge with the power to inspire and encourage people in ways that have never been approached before. The clandestine but heroic efforts of the Jarrett House and Witten Street homeowners should never be forgotten. To me, these are bona fide 19th century freedom fighters who worked to maintain these residences on Pocahontas Island. They had to push past the fear of being caught harboring fugitives, to boldly defy the law, to place their community members at risk for the sake of resistance–these narratives are not only empowering but transformative.

From my purview, the Underground Railroad houses on Pocahontas Island are hidden treasures that illustrate the power of KUJICHAGULIA, an African dialect word meaning “self-determination.” On a tiny island floating in the middle of the Appomattox, here you find an insular community of free Black people that were self-supported, self-governed, self-motivated, and self-guided to assist a steady stream of the less fortunate to grasp their own freedom by stepping into the water and onto a boat docked in the backyards of total strangers, headed for the unknown. The fact that two of the houses are indisputably verified to have been deeply involved in Underground Railroad activities just further punctuates our responsibility to tell this story in a way that highlights resilience, resistance, the reclamation of hidden history, the power of doing for self and working together towards a common goal.

Describe the impending threat to your site. (How imminent is it?)

These two verified Underground Railroad station houses are in a state of disrepair. If they are not preserved, they will be lost forever. One is owned by the city, one by a private owner who I am hoping will be willing to donate the property so that I can begin to raise renovation funds and repurpose it into a place to inspire and educate visitors to the island about Ancestral Remembrance and the path to freedom. These houses are exposed to the elements, are uninhabited and not being preserved nor renovated in any way beyond basic joists and boarded windows.

Describe the setting and context. (Does the site retain its original character? What does the surrounding area look like?)

Pocahontas Island has all the features needed to become a destination for learning about the path to freedom, the Civil War, the 19th century resistance movement, a historical ethnic enclave, and more. There is space to erect signage to tell this story on a walking tour of the island, plus an opportunity to convert these buildings into learning spaces. There’s plenty of space to park, to explore, to enjoy the river at a park or fishing dock, to have reunions, to hold festivals or any number of options that I am looking forward to seeing develop as a result of this nomination being accepted.

Who is involved in the effort to save your site? (i.e., an organization, local government, a historical society, Main Street program, etc.) Have these organizations made a financial commitment to the effort? Are there any groups that oppose the preservation of your site?

I am submitting this nomination after having traced my own family to Pocahontas Island all the way back to 1870. I am an independent historian with a primary focus on reclaiming hidden local history. I founded a collaborative community project called #untoldrva, which presents little known narratives in creative, engaging ways to inspire everyday people with fascinating headlines taken directly from the bygone era. In this effort, I have built up a network of over 200 partners from all walks of life who all love Richmond’s surrounding areas and are committed to working towards this shared goal of SANKOFA: going back to reclaim what was once lost.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 3 reader comments. Read them.