Civil War: The Siege of Petersburg begins

150 years ago this week, a ten-month siege begins just south of Richmond.

After the botched assault at Cold Harbor in early June 1864, Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, situated just north of the city of Richmond, decided to change tactics. His enemy, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, was planted firmly between him and Richmond. Grant still believed in a war of attrition, but needed to force Lee’s hand to either get him out of the protection of Richmond or into an open field of battle.

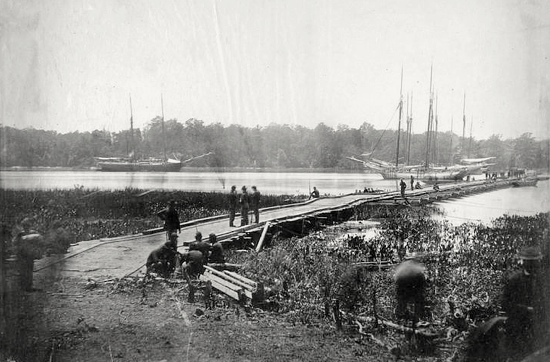

In a secret move undetected by Lee, Grant moved his army eastward along the James River. Once out of range of Confederate reconnaissance, Union army engineers built the largest pontoon bridge of the Civil War on June 14th. At 700 yards in length, it spanned the entire river, requiring the aid of several ships to keep it in place against the fast-moving current. It took about half a day to build and three days to move Grant’s forces, supply wagons, and artillery across the James River. Grant was now on the south side of the river and Lee was still unaware.

Grant’s target on the south side of the river was the city of Petersburg. Petersburg, a much smaller city than Richmond, held the key to supplying the Confederate capital. Five railroad lines converged in Petersburg and access to the Appomattox River made it the ultimate supply hub for Richmond. Without Petersburg, Richmond would be totally cut off and there’d be no way for Lee to defend the city and not put his army at risk. Fortunately for the Confederates, they knew the strategic importance of Petersburg early on in the war and had built significant fortifications around the city in 1862. Built under the command of Captain Charles Dimmock, the “Dimmock Line” was ten miles of fortified earthworks connecting 55 artillery batteries–most of which were built by slave labor. In order to take Petersburg, Grant would have to break through those lines.

The Dimmock Line was defended by Confederate Gen. Henry Wise, who was governor of Virginia before the start of the war. Because so many men had been sent to reinforce Lee’s army north of Richmond, only 2,200 rebels were left to hold the line. Spread thin against a much-larger Union force, there was little they could do to hold them off; even the strongest fortifications need soldiers to defend them. On June 15th, the Union vanguard led by Gen. William F. Smith (among the first to cross the James River pontoon bridge) attacked the Dimmock Line. The attack, delayed on account of waiting for reinforcements to arrive, didn’t get started until 7:00 PM that evening. Union forces quickly overtook several batteries and attacked down the existing trench lines, easily dislodging the Confederate defenders. By nightfall, several batteries were in Union hands. Smith was unsure if the attack had been a fluke or if the rest of the Dimmock Line was this poorly defended. Without the benefit of daylight, he was hesitant to proceed any further and decided that the attack would resume in the morning.

Had they pressed further, Union forces could have easily overwhelmed the remaining Confederate defenses and taken Petersburg that night, likely bringing the war to a quick close that summer of 1864. Grant, whose boldness had characterized the entire Overland Campaign thus far, was not yet on the scene, so the typical Union “caution first” mentality was firmly in place. On June 16th, the Union army resumed attacks on the Petersburg defenses, but found that reinforcements had arrived. Lee was moving his army south to defend the city. In addition, the rebels had already begun to dig new earthworks several yards away from the fortifications that the Union had overtaken. For four days, Union forces continued to attack the defensive positions with no meaningful results.

The Confederate and Union soldiers at Petersburg didn’t know it yet, but they were about to embark on a ten-month staring contest from their respective trenches. The siege of Petersburg had begun: a muddy mess of miserable trench warfare with the highest stakes imaginable. Richmond’s (and the Confederacy’s) future would be determined by what happened here.

Settle in, readers. We’ll be reporting live from the trenches for a while. Fortunately for us, there are plenty more stories to tell.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 6 reader comments. Read them.