Civil War: Cold Harbor

June of 1864 brought the Civil War once again right to Richmond’s doorstep, where it would stay for the remainder of the war.

Yesterday morning, our city was awakened by the roar of battle, which began with the dawn, between Lee and Grant’s armies. The cannonade was very heavy, and the rattle of the musketry was also distinctly heard from the hills around the city. Richmond Sentinel, 6/4/1864

June of 1864 brought the Civil War once again right to Richmond’s doorstep, where it would stay for the remainder of the war. Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s “Overland Campaign” had steadily brought the fight closer to the capital city. The central strategy behind Grant’s campaign was “war by attrition,” a concerted effort to wear down Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia through continuous fighting. Where previous Union generals had fallen back or retreated to Washington after major battles, Grant pressed onward. The map of troop movements over the summer of 1864 shows a clear pattern of attempted flanking movements. After each battle, the Union army headed southeast, in an attempt to cut off Lee’s army from the supply lines of Richmond. Each time, the rebels quickly moved to check Grant’s advances–but at the start of June, Lee found himself a dozen miles north of Richmond with less and less room to maneuver. Keeping Grant in check had come at a price as well. While some reinforcements had arrived at the end of May, Lee’s army was still much smaller than Grant’s continually-reinforced Union army.

After fighting at Totopotomoy Creek in late May, Grant ordered the Union cavalry under Gen. Philip Sheridan south to capture a strategic crossroads at a place called Old Cold Harbor on May 31st. There, they encountered Confederate cavalry led by Gen. Fitzhugh Lee. After a brief skirmish at the crossroads, the Confederates fell back about half a mile south. Anticipating more fighting to come, the rebels started digging entrenchments there. The next morning, Confederate forces made an attempt to retake the crossroads, but were pushed back. Grant was encouraged by this development and planned to center his next major assault there, breaking through Confederate lines and finally come between Lee and Richmond. After a day of fighting back and forth, the crossroads remained under Union control, but they were still unable to dislodge the Confederate force to the south. Additional Union forces under Gen. Winfield Hancock were set to arrive overnight for a planned assault in the morning, but the night march had left his soldiers exhausted and unable to go into battle. Grant planned to delay his assault until 5:00 PM which stretched into an even further delay of 5:00 AM the morning of June 3rd. These delays would spell disaster for the Federal troops.

While Hancock’s men were resting up, Lee’s army was busy digging in. Lee, known early in the war as the “King of Spades” for all the defensive earthworks he oversaw built in and around Richmond, coordinated the building of more significant entrenchments south of the crossroads. In the day it took Grant to coordinate the assault, Lee had built a series of fortified trenches set at angles to allow for deadly enfilading fire on the impending Union assault. To add to Lee’s good fortune, very little Federal reconnaissance had taken place that day, so the Union command was largely unaware of how extensive the new Confederate defenses were.

They would find out the next morning.

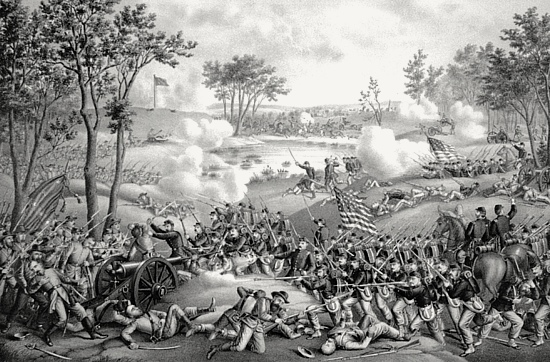

The June 3rd assault was scheduled to begin at 4:30 AM. Grant felt that a massive, well-coordinated frontal attack with his superior numbers could overwhelm and break the Confederate army. Union troops formed in a solid line of men across the entire front and began the attack. The uneven swampy ground quickly turned the coordinated line into an uneven, broken one as a sea of blue charged across the field. Once they reached the range of the Confederate rifles, it barely mattered. In the first thirty minutes of the assault, an estimated 7,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded. Entire columns of Union soldiers were mowed down by rifle and artillery fire. It was a bloodbath from the first minutes, and it would continue for several more hours until Grant finally called off the assault at 12:00 PM.

Later that night, Grant remarked “I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered. I regarded it as a stern necessity and believed it would bring compensating results; but, as it has proved, no advantages have been gained sufficient to justify the heavy losses suffered.” Northern newspapers would be unforgiving–referring to Grant, whom they praised earlier for his relentlessness against Lee, as a butcher.

Unable to move forward or retreat, many Union soldiers pinned down on the battlefield began digging in themselves. They made improvised shovels out of bayonets and cups, shielding their efforts from Confederate sharpshooters with the bodies of their fallen comrades. These improvised trenches, often only yards away from the Confederate trenches, would serve as the Union trench lines for the next several days of fighting. No one under Grant’s command had the stomach to make another attempted assault, so they settled into several days of trench warfare. Without knowing it, the soldiers on both sides were getting a sneak preview of the type of warfare that awaited them further south outside Petersburg. Sporadic sharpshooter and artillery fire made life in the trenches deadly in addition to miserable.

The fate of the Union wounded was much worse. After the failed assault, thousands of wounded Union soldiers lay on the battlefield waiting for help that never arrived. Perhaps not wanting to show weakness after such a devastating defeat, Grant refused to request a flag of truce to retrieve the wounded from the battlefield. It wasn’t until several days later that a two-hour break in the fighting was formally requested. By that time, there were no wounded left to recover, only blackened corpses decomposing in the hot summer sun.

The Battle of Cold Harbor would be Lee’s final victory during the Civil War and Grant’s biggest misstep. On June 12th, Grant withdrew across the James River and headed south to Petersburg, which would be where the two armies would face off for the rest of the war. Stay tuned for the story of the siege of Petersburg later this month.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.