Civil War: Lincoln arrives in Richmond

Honest Abe stops in to measure the drapes!

On April 4th, 1865, two days after Richmond was abandoned by the Confederate government, parts of the city were still burning and smoldering. The fires, set by departing soldiers, left charred smoking rubble through much of what is now downtown. Union forces had arrived early on the morning of April 3rd and had spent most of the first 24 hours taking stock of the situation, putting out fires, and setting up headquarters in now-empty government buildings. Citizens of Richmond were still in a state of shock–responses to Richmond’s capture ranged from Confederate loyalists hiding indoors with curtains drawn to expressions of jubilation from the formerly-enslaved black population, now free under Union authority. In this time of transition and uncertainty, just two days after the city fell, Richmond had a very unlikely visitor–President Abraham Lincoln.

Before we continue, I think it’s important to pause and acknowledge how absolutely crazy this all sounds 150 years later. These days, if a president desires to go anywhere, he or she must first undergo an elaborate vetting and security process, crowd control, and secret service everywhere. Lincoln strolling into Richmond is the modern-day equivalent of President Barack Obama airdropping into Baghdad in 2011 on the day after the end of operations in the Iraq War and walking through the streets to check things out. NOT A GREAT IDEA, right? To be fair, even 150 years ago, there were some definite concerns about security. As Richmond and Petersburg fell to Union forces, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton sent a telegram to Lincoln basically saying “Hey, don’t do anything stupid, okay?” It read:

“I congratulate you and the nation on the glorious news in your telegram just read. Allow me respectfully to ask you to consider whether you ought to expose the nation to the consequences of any disaster to yourself in the pursuit of a treacherous and dangerous enemy like the rebel army. If it was a question concerning yourself only I should not presume to say a word. Commanding Generals are in the line of their duty in running such risks. But is the political head of nation in the same condition.

(More at Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Lincoln basically responded “Yeah, okay, I hear you but..” and telegrammed back: “It is certain now that Richmond is in our hands, and I think I will go there to-morrow. I will take care of myself.”

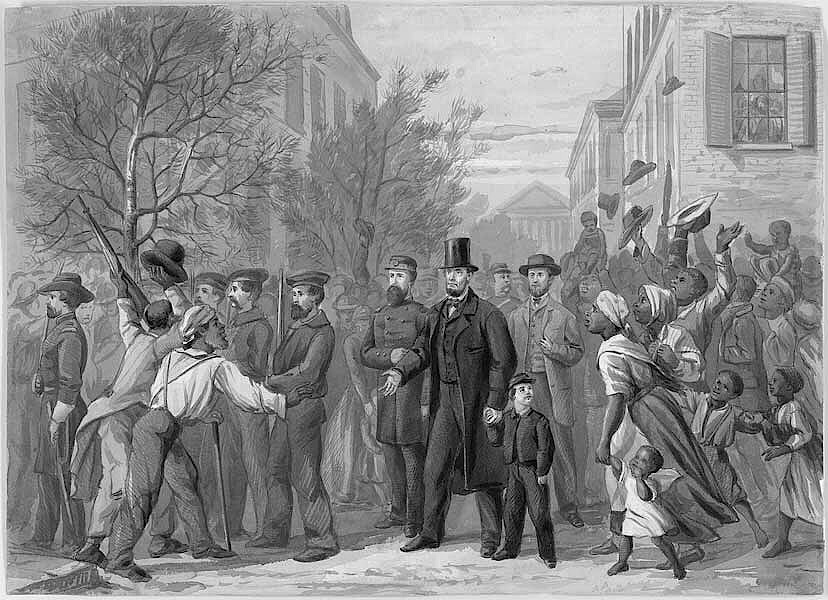

Lincoln left the Union headquarters at City Point, Virginia and traveled up the James River by boat, arriving at the wharf at Rockett’s Landing in the early afternoon. As Lincoln and his small entourage walked up toward the city, several newly-freed slaves recognized Lincoln and shouted out to him, expressing their gratitude and calling him “Father Abraham.” Word spread like wildfire among the black population and soon a large crowd gathered to walk with Lincoln as he entered the city, singing hymns and shouting praises alongside him. Soon, the size of the crowd became oppressive and it was actually difficult for Lincoln and his contingent to push through and navigate their way to their destination–the White House of the Confederacy.

When the crowd appeared to reach its peak, Lincoln felt moved to speak. One of Lincoln’s escorts, Admiral David D. Porter, recalled his words (likely with a dose of rose-colored embellishment) to the newly-emancipated:

My poor friends, you are free–free as air. You can cast off the name of slave and trample upon it; it will come to you no more. Liberty is your birthright. God gave it to you as he gave it to others, and it is a sin that you have been deprived of it for so many years. But you must try to deserve this priceless boon. Let the world see that you merit it, and are able to maintain it by your good works. Don’t let your joy carry you into excesses. Learn the laws and obey them; obey God’s commandments and thank him for giving you liberty, for to him you owe all things. There, now, let me pass on; I have but little time to spare. I want to see the capital, and must return at once to Washington to secure to you that liberty which you seem to prize so highly.”

(More at Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Upon completion of his impromptu speech, Lincoln made his way up the hill to the former residence of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Upon arriving, he settled in Davis’s office, where he sat in his chair and seemed to quietly reflect on the changing fortunes of the war–it finally felt like it would all soon be over. Several of the soldiers accompanying him discovered a store of liquor, and congratulatory drinks were shared by all–except Lincoln, who contented himself with a glass of water. Lincoln had lunch and held a handful of meetings in the office, then set out to explore the house. An aide, Thomas Graves, shared a personal anecdote about Lincoln’s explorations:

At length he asked me if the housekeeper was in the house. Upon learning that she had left he jumped up and said, with a boyish manner, ‘Come, let’s look at the house!’ We went pretty much over it; I retailed all that the housekeeper had told me, and he seemed interested in everything. As we came down the staircase General Weitzel came, in breathless haste, and at once President Lincoln’s face lost its boyish expression as he realized that duty must be resumed.

(More at Eyewitness to History)

After arranging for a carriage to transport them back to their boat, Lincoln left the Confederate White House and headed back to Rockett’s Landing. The streets were thronged with additional well-wishers and cheering crowds, both black and white citizens alike. By 6:00 PM, Lincoln was back aboard his boat on the James River and on the way back to City Point. The walk through Richmond, while brief, had the desired impact. Lincoln arrived in the city not as a conquering hero or dictator, but as someone with open arms, seeking reconciliation and reunion.

In retrospect, the president’s trip was more fraught with danger than anyone realized, but in ways that weren’t really discovered until after the fact. The section of the James River that had to be navigated in order to arrive at Rockett’s Landing was discovered later to be chock-full of explosive mines. Reports of possible snipers posted at windows in the city would later emerge. Not to mention the risk from the huge and unanticipated crowd that enveloped Lincoln during his walk through the city. Fortunately though, no harm befell the president that day–but death was still on his doorstep.

In ten days, Lincoln would be dead from an assassin’s bullet.

— ∮∮∮ —

Did you miss Richmond’s fall? Did you miss the rest of the Civil War series? Well, guess what! You’re gonna miss it for real, because there are only two more left! Stay tuned!

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.