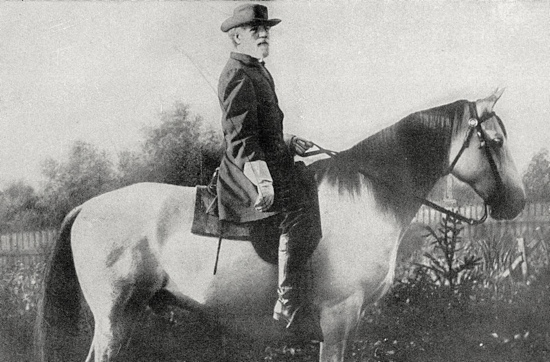

Civil War: Lee’s second resignation

150 years ago after his defeat at Gettysburg, Gen. Robert E. Lee would tender the second resignation of his career.

For the second time since the Civil War began, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee found himself writing a letter of resignation.

The first was written in 1861 at the outbreak of war, when he made the difficult decision to resign his commission in the United States Army in order to fight for the Confederacy. The second was written in the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg. Lee had been on the run since July 4th, retreating south through Maryland to the safety of the southern side of the Potomac River. Union Gen. George Meade was slow to act and didn’t gain the momentum in time to stop Lee from reaching Virginia, but Union forces harassed Lee’s retreating army at various points along the way, making the retreat a difficult one for the Army of Northern Virginia.

Once they arrived safely in Virginia, Lee had a chance to reflect on the condition of his battered army which saw 23,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or captured in Gettysburg. In addition, reports from Southern newspapers reached Lee that spoke critically of his performance in the battle. On August 8th, from his camp in Orange, VA, Lee wrote a letter to President Jefferson Davis, asking to be relieved of his duty:

I know how prone we are to censure and how ready to blame others for the non-fulfillment of our expectations. This is unbecoming in a generous people, and I grieve to see its expression. The general remedy for the want of success in a military commander is his removal. This is natural, and in many instances, proper. For, no matter what may be the ability of the officer, if he loses the confidence of his troops disaster must sooner or later ensue.

I have been prompted by these reflections more than once since my return from Pennsylvania to propose to Your Excellency the propriety of selecting another commander for this army. I have seen and heard of expression of discontent in the public journals at the result of the expedition. I do not know how far this feeling extends in the army. My brother officers have been too kind to report it, and so far the troops have been too generous to exhibit it. It is fair, however, to suppose that it it does exist, and success is so necessary to us that nothing should be risked to secure it. I therefore, in all sincerity, request Your Excellency to take measures to supply my place. I do this with the more earnestness because no one is more aware than myself of my inability for the duties of my position. I cannot even accomplish what I myself desire. How can I fulfill the expectations of others?

Lee also went on to describe his physical fatigue and limitations that he felt made him unfit for command. After making his case, he continued:

Everything, therefore, points to the advantages to be derived from a new commander, and I the more anxiously urge the matter upon Your Excellency from my belief that a younger and abler man than myself can readily be attained. I know that he will have as gallant and brave an army as ever existed to second his efforts, and it would be the happiest day of my life to see at its head a worthy leader–one that would accomplish more than I could perform and all that I have wished. I hope Your Excellency will attribute my request to the true reason, the desire to serve my country, and to do all in my power to insure the success of her righteous cause.

The letter arrived to Jefferson Davis and he wrote back to Lee on August 11th, 1863. Davis’s response? “Hell no, you can’t resign!” OK, so it was definitely much better written than that, but as shown in this excerpt, it was clear that Lee wasn’t going anywhere:

To ask me to substitute you by someone in my judgment more fit to command, or who would possess more of the confidence of the army, or of the reflecting men of country, is to demand an impossibility.

It only remains for me to hope that you will take all possible care of yourself, that your health and strength may be entirely restored, and that the Lord will preserve you for the important duties devolved upon you in the struggle of our suffering country for the independence which we have engaged in war to maintain.

Whether Lee offered up his resignation because he was physically exhausted or if it was a question of honor (or most likely, a combination of the two), he would continue to heed Davis’s request and lead the Army of Northern Virginia until the war’s end in 1865. It’s hard to imagine the consequences had Lee had been permitted to resign, but it’s likely that any replacement would have paled in comparison and likely would have resulted in a Union victory much sooner than 1865.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 4 reader comments. Read them.