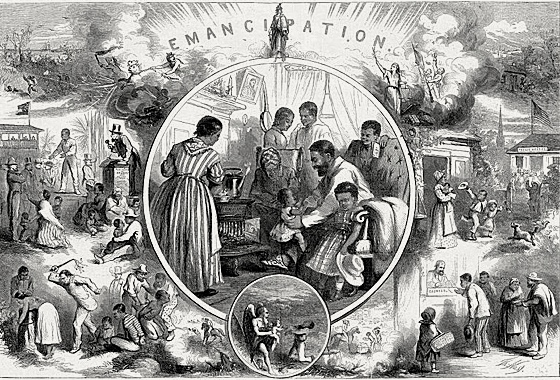

Civil War: Emancipation

While the impact may not have been felt immediately in Richmond, January 1, 1863 brought a significant event that would change the course of the Civil War.

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom. Emancipation Proclamation, 1/1/1863

While the impact may not have been felt immediately in Richmond, January 1, 1863 brought a significant event that would change the course of the Civil War. On that day in Washington D.C., Abraham Lincoln signed and issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all slaves held in the rebel states were now freed. In addition, it allowed for the forming of African American regiments to fight for the Union.

While the document had far-reaching political impact, the Emancipation Proclamation had very little impact on the lives of those enslaved in the South at the time it was issued. However, as the war continued, and the Union pushed further into Confederate territory, many thousands of slaves would find themselves freed as a result. In Richmond, it likely had an impact on the number of runaway slaves attempting to reach freedom across the Union lines. Numerous runaway slave notices appeared in Richmond’s newspapers, such as this one from the following week:

From the C. S. shops, Bacon’s Quarter Branch, Richmond, Va., on Tuesday, the 6th inst., a negro man, named William, (a blacksmith by trade) Said negro was purchased in Warren county, N. C., from the estate of Peter Powell, dec’d, by Brittingham & Gwin, or Mr. Dupree, and brought to Richmond and resold to Hatcher & Webster. Said negro is about five fifteen inches high, copper colored complexion, with a pleasing countenance. He had on when he left a gray mixed suit of clothes and gray cap. He has a scar on one of his legs, (the one not remembered,) caused by a kick from a mule. It is supposed he left with General Ransom’s division, as it passed through on that day, perhaps having met with some acquaintance and told a plausible tale. I will pay a reward of $25 for said negro if arrested in the city of Richmond: $50 if taken in the State of Virginia; or $100 if taken out of the State, and confined in any jail, so that he can be procured, or delivered to Hill, Dickinson & Co. Auct’s, or to the undersigned. Richmond Daily Dispatch, 1/9/1863

Going through these runaway notices, it was difficult to read about slaves discussed so casually as property. Difficult too, was reading the response from Confederate president Jefferson Davis. He remarked that the Union intended “to incite servile insurrection and light the fires of incendiarism” and “debauch the inferior race by promising indulgence of the vilest passions.” The South had always feared the possibility of a slave uprising and they felt that the Emancipation Proclamation was intended to bring about that result.

Allowing African American soldiers to fight for the Union was especially outrageous in the South, sparking many in the Confederate congress to seek retaliatory measures:

Mr. Lyons, of Virginia, [introduced] a resolution exhorting the people of the Confederacy to kill every officer, soldier, and sailor of the enemy found within their borders unless a regular prisoner of war; declaring that after the 1st of January, 1863, no officer of the enemy ought to be captured alive, or if recaptured should be immediately hung; and offering a bounty of twenty dollars, and an annuity of of twenty dollars for life to every slave and free negro who shall, after the 1st of January, 1863, kill one of the enemy. The Virginia Legislature resolved to grant immunity to any person who may kill any parties found on the sacred soil, armed or unarmed, aiding to carry out the ‘fiendish purposes’ of the proclamation. Harper’s Weekly, 10/18/1862

Regardless of the response in Richmond, reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation elsewhere would have the impact Lincoln desired. It helped to turn international perception of the Union’s cause to be a fight for freedom from slavery, ensuring the support of countries like Great Britain and France. As the war neared its end, Lincoln would push to ensure that his proclamation, largely considered a war measure, would not be in vain. He worked tirelessly for the passage of a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery throughout the United States.

The story of his fight for the 13th Amendment is the main focus of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, which people who live under rocks might be surprised to learn was shot right here in Richmond.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 5 reader comments. Read them.