History reconstructed: Assembly honors black lawmakers

Legislators have passed a pair of resolutions describing the contributions of the pioneering lawmakers and praising them for their “commitment to public service in the face of deep resentment, racial animus, violence, corruption, and intimidation.”

From Capital News Service, Sherese A. Gore

“Remember, girls, you’re not anyone; you’re Virginia Teamohs!”

At home in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, that’s what Rafia Zafar’s Southern-born grandmother would say to keep her granddaughters in line. Years later, Zafar, a Harvard-educated English professor at Washington University in St. Louis, would come to realize the significance of those words.

Zafar’s great-great-grandfather was George Teamoh, who was born a slave in Portsmouth in 1818 and became a state legislator after the Civil War. An accomplished orator and advocate of African-American self-help, Teamoh served in the Virginia Senate from 1869 to 1871.

Teamoh was one of about 100 blacks elected to the General Assembly during Reconstruction–until racial discrimination and Jim Crow laws relegated African-Americans to second-class citizenship. Those history-making legislators are finally getting recognition: They’re being honored by the 2012 General Assembly.

Legislators have passed a pair of resolutions describing the contributions of the pioneering lawmakers and praising them for their “commitment to public service in the face of deep resentment, racial animus, violence, corruption, and intimidation.”

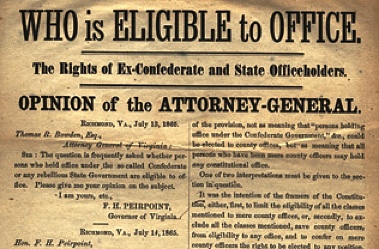

The resolutions, which were recommended by the Dr. Martin Luther King Memorial Commission, aim to dispel misconceptions about the role of blacks in the years immediately following the Civil War.

“For a long time, there was this mythology about Reconstruction in the textbooks which said that all these people were ignorant–they didn’t know what they were doing, they were corrupt and Reconstruction was a total disaster,” said Eric Foner, a history professor at Columbia University.

“And that’s just not true.”

Ten years after the Supreme Court denied U.S. citizenship to men, women, and children of African ancestry in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, black men would hold political office in most of the former slave-holding states and be elected to the U.S Congress.

Notable Legislators during Reconstruction

James Bland–Considered the voice of compromise and impartiality, he represented Appomattox and Prince Edward counties in the Virginia Senate. He died in the 1870 floor collapse at the Capitol that claimed 60 lives.

William Brisby–He represented New Kent County in the House of Delegates. Brisby reportedly helped Union soldiers escape from Richmond during the Civil War.

Nathaniel Griggs–Before representing Prince Edward County in the House of Delegates, Griggs, a former slave, was fired from his job as a tobacco factory worker for making political speeches.

Charles and John Hodges–These brothers represented Norfolk and Princess Anne counties respectively in the House of Delegates. Their family was active in the abolition movement during slavery and forced to flee to the North before the war.

Henry Smith–He represented Greensville County in the House of Delegates in 1879-80. Born a slave, Smith would own more than 900 acres, including the residence of his former owner.

Virginia’s black legislators hailed from a myriad of educational and economic backgrounds: free-born and former slave, impoverished and well-to-do, highly educated and functionally illiterate.

All were Republican, the party of Abraham Lincoln and emancipation.

The lawmakers served on legislative committees and introduced such forward-thinking proposals as prohibiting the sale of liquor to minors, abolishing the whipping post as a form of punishment, and treating blacks and whites equally in public places.

Joseph Evans, who represented Petersburg in both the House and Senate, proposed requiring landlords “to give ten days’ notice before evicting a tenant.”

A measure defining the “boundaries of election precincts” was introduced by Peter Jacob Carter, a runaway slave who enlisted in the 10th Regiment of the U.S. Colored Infantry.

Matt Clark, who represented Halifax County in the House of Delegates, proposed the “refinancing of the state war debt at a lower interest rate” to subsidize Virginia’s new public school system.

— ∮∮∮ —

Hostility from White Virginians

Black legislators and other African-Americans were the targets of intimidation after the Civil War. Throughout the South, campaigns of terror were aimed at the freedmen, members of the Republican Party and whites sympathetic to the plight of black citizens.

In addition, the Democratic Party would enact restrictive voting requirements and other laws to marginalize African-Americans and their chosen representatives at the General Assembly.

For example, Democrats removed Phillip Bolling from the House of Delegates on grounds that his employment at a brick kiln in Prince Edward County disqualified him from representing Buckingham and Cumberland counties in General Assembly. Other black legislators also felt pressure.

“They faced an enormous amount of hostility from a large number of white Virginians,” said Foner, who won the Pulitzer Prize in history for his 2010 book, “The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery.”

“And that made it even more difficult for them to carry out their responsibilities.”

By the late 1880s, most black legislators had been forced from public life. Many would become merchants (such as James F. Lipscomb, who opened a country general store in Cumberland County), lawyers (such as Richard G. L. Paige, who had a law practice in Norfolk) or preachers (such as Guy Powell, who became pastor of a Baptist church in Brunswick County).

Some moved north, such as Tazewell Branch, who settled in New Jersey after representing Prince Edward County in the Virginia House from 1874 to 1877.

The legacy of these groundbreaking officials faded into obscurity, save for the occasional highway marker (one in Cumberland County honors Lipscomb) or family lore about ancestors like George Teamoh.

It would be nearly a century later, after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, that blacks would resume holding public office in earnest. The Virginia General Assembly would not see its first African-American lawmaker until the election of Dr. William Ferguson Reid to the House of Delegates in 1968.

The forgotten history is why Delegate Jennifer McClellan of Richmond introduced House Joint Resolution 65, “recognizing the African-American representatives to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868 and members elected to the Virginia General Assembly during Reconstruction.”

“They did a lot of significant things while they were in office that we don’t learn in our history class,” McClellan said.

Her resolution was approved unanimously by the House on Feb. 13. The Senate is expected to vote on it this week.

Another Richmond Democrat, Sen. Henry Marsh, is sponsoring Senate Joint Resolution 13. It won unanimous approval from the Senate on Feb. 6 and from the House on Friday.

Both resolutions provide a roll call of the African-Americans who were elected to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868 and to the General Assembly between 1869 and 1890.

“The people of the Commonwealth are indebted to these African-American public servants and are the beneficiaries of their tremendous contributions and service to help promote the promise of racial equality, justice, and full citizenship for all citizens,” the resolutions state.

Marsh, who chairs the Dr. Martin Luther King Memorial Commission, said the recognition of the Reconstruction-era black legislators is long overdue.

“It’s a remarkable story,” he said. “In my mind, they are real heroes.”

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.