Coming down the pipe: RVA water and sewage infrastructure

At RVANews Live, we will be capitalizing on this aromatic piece we did a little bit ago, as well as many other pieces about city infrastructure!

You asked, we delivered. MORE on sewers and water mains, you said. MORE on the way the city works, you said. We said “OK, weirdos,” and scheduled one of our RVANews Live panels to discuss just these things! Buy your ticket now, because it is this Thursday! Now, for a fascinating refresher…

— ∮∮∮ —

Be warned. This article will take you down an unfortunately gross hole, in which you will conjure mental images that you can never unconjure. But such is the predicament of being human. If you want even more info, check out Martin Melosi’s The Sanitary City: Environmental Services in Urban America from Colonial Times to the Present

We use city water pipes every day to bring water into our homes and businesses. And we use sewers every day to take waste out.1 Lately, we’ve had a fair amount of problems with our water mains, which resulted in some back-and-forth with the city about whether we should or should not boil our water.

And our outdated combined sewer overflow system keeps us constantly trying to keep up with the amount of gross stuff we’re dumping in the river. Bob Steidel, director of Richmond’s Department of Public Utilities, explains what we don’t have in some of the older parts of the city.

There are three kinds of pipes that take waste. Sanitary sewers take waste out of houses and restaurants and businesses, from what you flush down a toilet or wash out of a sink to what you’d use to make a product. Sanitary sewers go into a treatment plant. The second type of sewer is called a storm sewer, and that’s just made to take storm runoff and snow melt. The only thing it touches is the land, and it usually goes directly into the river. The third sewer is a combined sewer.

Combined Sewer Overflow systems (or CSOs) channel stormwater and raw sewage together in certain situations. Many older cities, including ours, are working on updating this problem. And here’s why!

The history of RVA’s sanitary practices

Ellen Chapman of RVA Archaeology looked into the question for me–an unpleasant question that I hope someone more considerate followed up with “Has anybody found a historic beautiful flower garden layout buried beneath a contemporary beautiful flower garden?”

Her findings were fascinating, so much so that I found myself looking up “gong farmer” and sending pics of cesspools to my (former) friends. It’s crazy that one of the most important parts of being a grownup civilization is shit storage. In order to forget about the waste products of our own bodies, we have to hire people whose job it is to think about it. It’s delegating our very thoughts to others. And it’s genius.

Municipalities only stepped in 150-200 years ago, explains Chapman. The world of well-digging, cisterns, and creeks had been bringing water to individual families, and privies, cesspits, or simply streams and rivers were doing the dirty work for those same families. “Between roughly 1830 and 1890, American cities began to treat water and sewage disposal more as a public health program than a private matter,” says Chapman, “Probably helped by research in London by a man called John Snow, who used an early spatial analysis to determine that cholera was spreading through infected water sources.”

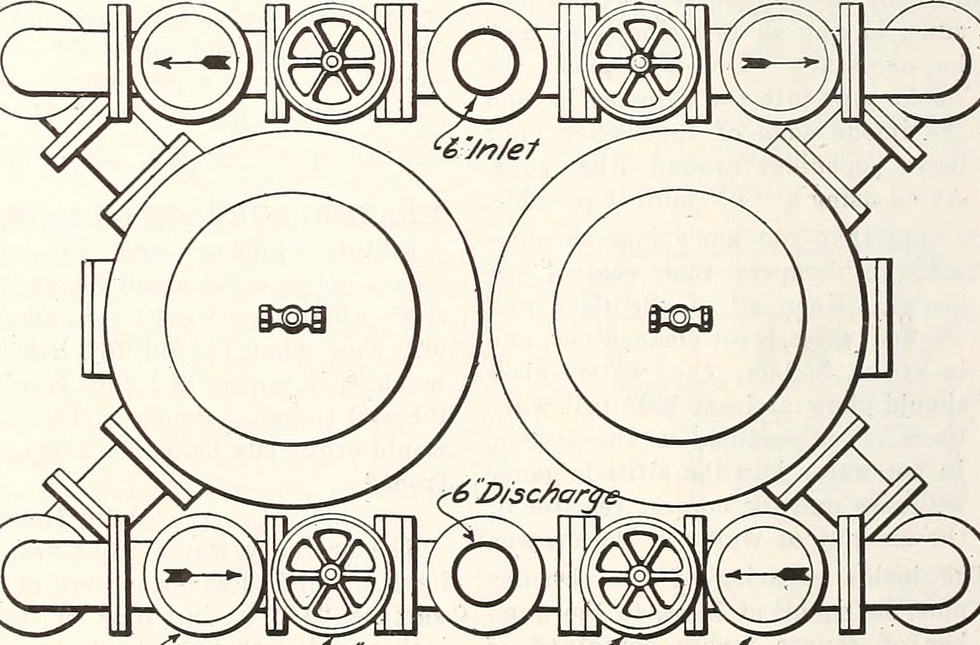

First, we had wooden water pipes (the bringing-in pipes), which we discovered several times in the 1950s at 12th and Cary (some of which the Valentine still have in their collection). “Starting in 1831, cast iron pipes carried water from pumphouses in the city, which used the power of the James to raise water to hilltop water towers that serviced the rest of the city,” says Chapman. “A similar private company did the same for Manchester. One amazing relic of early city water system is the Byrd Pumphouse, which housed three massive waterwheels and their attached turbines.”2

In the late 19th century, the taking-away pipes got larger and larger in diameter as they extended towards the river (according to maps from the Office of the City Engineer). “These systems did not keep storm water, waste water, and sewage separate, as the prevailing wisdom then was that pollution could be effectively diluted, and storm water helped to periodically clean the sewage pipes. Once cities realized that this system was fouling the rivers, and contributing to infectious disease, this combined system was well-established,” Chapman says.

Courtesy of Richard Hayes.

Up a certain creek

Whoops! And that’s where we are now. The Clean Water Act has spurred the city spend millions each year on gradually replacing this system with a modern one, requiring municipalities to reduce the amount of harmful waste they put into rivers.

Bob Steidel assured me that, “All cities that have combined sewers are in the process of doing one of two things: either we’re eliminating them altogether or we’re treating the water in a modern water plant. We’re going to capture it and treat it. We started this project back in the 80s, and we’re about halfway done at this point. We’ve spent a little over 500 million dollars and have 750 million dollars to go.”

In the meantime, “there are still regular flood/rain events that overwhelm the city’s system, which end up releasing large quantities of untreated sewage into the James River–notably, around 14th St in Shockoe Bottom,” says Chapman.

Though Steidel says that the city is working as hard as it can (spending between 10 and 20 million dollars each year), the key to reducing this output is simply using less water.3 “Everyone is going to zero discharge. We need to be able to reuse everything and use as little possible, and not put everything back simply into the river, but reuse and recycle everything in a big loop. The water that you drink would become the water of waste, which would become the water that you drink again. The ultimate in efficiency would be to close that loop and simply use that resource over and over again.”

And so much of allowing for a sewer system to scale to a city is thinking ahead. “What we’re trying to do first of all is use the right amount of water and use it wisely. And then when we’re repairing, we want to use the right-size pipe and right-size material for how we expect our customers to behave over the next 50 years or so.” It boggles the mind (and wrinkles the nose) if you are not an urban engineer, so let us be thankful that those exist.

But there’s some beauty in it

Because Ellen Chapman is exceptionally skilled at digging into sometimes very unsanitary places to find historically significant meaning, she points out the value of uncovering all of these old ways to deal with sewage.

“In terms of archaeology, water, and sewage, archaeological excavation certainly does find disused pieces of infrastructure quite often–capped wells, filled privies, cistern tanks made of brick, ceramic, and metal pipes. Some of them can be quite dangerous, because these types of structures often aren’t on surviving maps and can conceal voids which collapse upon exposure,” she explains.

“However, if they are located safely, they can be goldmines. Because of the soft landing and waterlogged environment, items found in wells and privies are often much more complete than usual. We find materials like textiles, leather, and paper much more commonly in these contexts. Additionally, a privy is a nice place to conceal something you don’t want exposed, so historical archaeologists are often finding signs of illicit alcohol use and other tantalizing glimpses in these contexts. And sometimes, people accidentally drop something into wells and privies, so there are occasionally entertaining finds, like chamber pots that someone likely lost hold of. One remarkable example of a privy discovery is in Cincinnati, where a policeman appears to have dropped his badge, bullets, uniform, whistle, and gun down the toilet. That discovery led to some archival research and the discovery of quite a sad story behind it.

Here’s hoping Richmond water and sewage pipes do not become a sad story. In the meantime, reduce your water consumption as much as possible and consider interesting your kid in the journey of water to the toilet and then poop to the river. They may just figure out the perfect solution one day.

- Assuming you don’t use an alternative method that we most likely do not want to know about. ↩

- “At the turn of the century, large social dances were held in an open-air ballroom on the building’s top floor,” Chapman informed me. Learn more about restoration of the Byrd Pumphouse. ↩

- I’m not sure how to tell you to reduce your own personal output, if you know what I mean. ↩

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 2 reader comments. Read them.