The beginning and end of the Siege of Yorktown

Gen. John Magruder and his troops waited as they watched Union Gen. George McClellan bring up more soldiers and artillery to lay siege to Yorktown. Outmanned nearly 10-to-1 before the siege even began, Magruder knew their days at Yorktown were numbered.

This is the second part of a two-part series on the Battle of Yorktown–if you haven’t read the first part, check it out here.

The siege of Yorktown had begun.

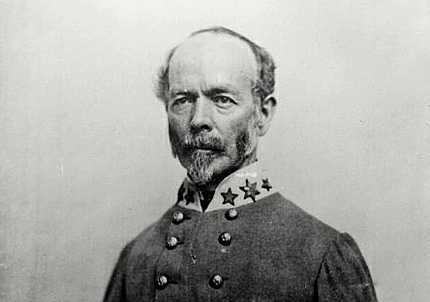

Fortified on a line along the Warwick Creek, Gen. John Magruder and his troops waited as they watched Union Gen. George McClellan bring up more soldiers and artillery to lay siege to Yorktown. Outmanned nearly 10-to-1 before the siege even began, Magruder knew their days at Yorktown were numbered. His task was to keep up the illusion of superior numbers until Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army could arrive and reinforce him. Even after several days of reconnaissance and probing Magruder’s fortifications for weak spots, McClellan still believed he was facing a larger enemy. A handful of captured Confederate prisoners helped to strengthen this illusion, providing McClellan’s interrogators with significantly exaggerated troop levels.

After a few more days passed, it became clear that McClellan would wait for his heavy artillery to arrive and be put into place before starting a major assault on Yorktown. This delay allowed enough time for Johnston to arrive at Yorktown with the reinforcements Magruder had been waiting for, strengthening the Confederate position. However, it still wasn’t going to be enough. Once McClellan’s artillery was fully in place, the huge guns would practically pound the Yorktown line out of existence.

A serious debate between Johnston and the Confederate leadership began: should they hold out at Yorktown or fall back to Richmond? One of the ideas floated was to keep McClellan at bay in Yorktown while another army headed up to Washington to harass the Union capital to draw McClellan back to a defensive position. Johnston wanted to fall back to Richmond, but Jefferson Davis ultimately ordered him to stay at Yorktown as long as it was feasible.

Since the Confederate army was staying put, the two armies dug in. It was a dull waiting game punctuated by artillery fire and deadly sharpshooters keeping both sides on edge. Several weeks went by as Union engineers worked tirelessly to transport, mount, and fortify several batteries of heavy artillery at the front. Soon they would be ready to unleash a deadly fire on the rebel army. On April 27th, Johnston sent word to Richmond that McClellan’s guns were almost ready and that his army would soon need to fall back. He began to make secret preparations to evacuate his army.

At McClellan’s headquarters, evacuation was the furthest thing from their mind. Convinced they faced an army of massive size, they assumed that the Confederates had every intention of fighting. McClellan set the date for his massive artillery bombardment. It would begin at dawn on Monday, May 5th.

On the night of May 3rd, the Confederates’ artillery began a heavy bombardment of their own–almost every gun on the line firing simultaneously. After a long while, they fell still and no more shots were heard that night. The Union didn’t know it, but the artillery fire was masking the sound of Johnston’s army evacuating behind it.

The next morning, the Union soldiers awoke to find the rebel army gone. They climbed over the rebel fortifications to find an abandoned camp. According to author Stephen Sears, scrawled in charcoal on one of the tent walls was the phrase “He that fights and runs away, will live to fight another day, May 3.” (To The Gates of Richmond, pg. 62)

The Confederates were gone and marching back to Richmond. Despite wasting weeks preparing for siege warfare and building elaborate heavy artillery batteries aimed at a now-empty Yorktown, McClellan remained completely undeterred. In his mind, the retreat of his enemy in the face of his siege guns was a sign of great success. He believed he was the victor and that he had them on the run when in reality, he let them get away.

While the rebels would “live to fight another day,” there would be nowhere to fall back to after Richmond. They knew the capital must not fall. It was only a matter of time before McClellan’s army would be on Richmond’s doorstep.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.