Day #098: A plea for regionalism

Why regionalism matters, Richmond vs. The United States of America, and how three votes in Denver can teach Richmond everything it needs to know.

Inspired by Michael Bierut’s 100 Day Project, 100 Days to a Better RVA strives to introduce and investigate unique ideas to improving the city of Richmond. View the entire project here and the intro here.

- Idea: A 0.1% sales tax for regional infrastructure, a percentage breakdown of where those funds will be spent each decade, and a Greater Richmond Mayors Caucus.

- Difficulty: 5 — There’s no indication that either the counties or the city have any interest in working together.

The Richmond Metropolitan area is full of world-class culture, industry, and talent. Despite its strategic location, six Fortune 500 companies, Federal Reserve Bank, State Capitol, history, river, and too many other things to list, it’s still regarded as a small Southern city. Richmond is immediately capable of so much more, so what’s holding it back?

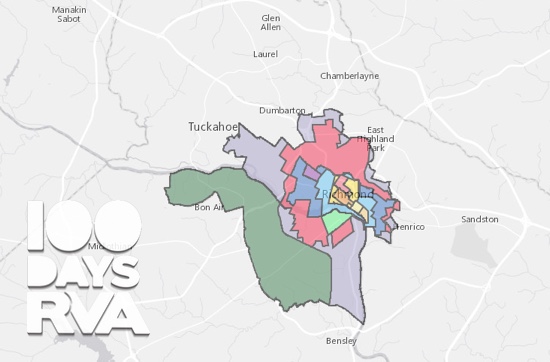

The City of Richmond ranks 99th in population with 214,000 people, right behind Boise, Idaho. Metropolitan Richmond’s 1.26 million people on the other hand ranks 44th and is ahead of many cities with bigger reputations. Because 83% of Richmond’s population lives in the suburbs, Richmond will continue to fail to reach its potential until it takes regionalism seriously.

Why regionalism matters

Regionalism is important because there are economies of scale in infrastructure and branding and because borders enable businesses and people to engage in extractive behavior.1

Economies of scale save money in regions and are present in cities in everything from public housing and water infrastructure to zoos and baseball stadiums. Economies of scale are also present in advertising and branding. Regionalism has cost savings that are captured by decreasing overlap and reducing administrative costs.

…these urban provinces, new to the American scene, possess greater economic, social, and cultural unity than most of the states. Yet, subdivided into separate municipalities…they face grave difficulties in meeting the essential needs of the aggregate population. Arthur B. Schlesinger (1940)

Metropolitan Richmond is one community divided by arbitrary lines. Borders force neighboring municipalities to compete instead of collaborating on issues like property taxes and sales taxes. This is most wasteful when it comes to economic development spending . Businesses who would choose areas based on their relative merits can instead pit municipalities against each other and extract taxpayers’ money in the form of incentives.

There’s an asymmetry to the patterns of life of Richmond residents and suburban residents. Suburban residents use city-funded infrastructure for employment and leisure in ways that simply aren’t comparable to the way city residents use suburban infrastructure.

To many in the suburbs, “‘regionalism’ is just another way of saying ‘send money to Richmond.’” So what motivations do the suburbs have to think regionally other than economies of scale and avoiding extractive behavior? The future.

The suburban paradigm of the last fifty years is coming to an end. The days of suburbs=good and cities=bad are rapidly disappearing because of changes in preference (millennials and retirees), rising transportation costs, debt overhang and willingness to take on debt, crime trends, and demographics. “Peak suburbs” is real.

The stalling of unbelievable growth in the counties combined with decreasing property values because of decreased demand will punish budgets. The unbelievable property taxes earned by booming suburbs between 1995 and 2007 were the result of an incomparable housing bubble with inflated prices. In the future, counties will find themselves with less revenue to cover budgets based on inflated incomes from the housing bubble. Also, all the new infrastructure the counties have built in the last two decades will start demanding more maintenance as they age.

Richmond is only 62.5 square miles and at a certain point it will run out of neighborhoods to gentrify. This will force an inversion of poverty. Instead of a poor city center surrounded by wealthy suburbs, a wealthy city center will be surrounded by a ring of poverty surrounded by a ring of wealthy exurbs. Now with Chesterfield and Henrico addresses, the poor will live in crumbling 1970’s homes in areas where transportation is nearly impossible without a car.

It probably won’t be this drastic, but the margin between booming suburbs and budget deficits is slim. The bottom line: the success of cities and suburbs is intimately connected. Regionalism is a way to hedge against trends while recognizing all the benefits of collectivism.

Annexation

It was never meant to be this way. In Virginia, cities were originally supposed to annex surrounding farmland as their populations and footprints increased. Richmond regularly did this between 1742 and 1970 (check out this amazing graphic).

The rapid expansion and independence of the counties combined with racially motivated annexation that resulted in the Supreme Court decision Richmond v. The United States (1975) forced the General Assembly’s hand in 1971 on its surprisingly urban-favoring policy on annexation. Since then, a combination of moratoriums and exemptions has ended any hope of Richmond annexing surrounding counties. Continued annexation would have allowed Richmond to realize economies of scale while eliminating the borders that arbitrarily divide the city and its population.

Denver

With annexation not a legal or practical solution, the best path to regionalism is through economic cooperation. In The Metropolitan Revolution, Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley examine regionalism in Denver over the last five decades. The Mile-High City offers a perfect model for Richmond to follow.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, Denver faced many of the same issues as Richmond. White flight was rapid and resulted in the forced busing of students in order to desegregate schools–an incredibly unpopular decision. Conditions worsened. Busing protestors bombed 1/3rd of the school bus fleet and the school board president regularly led protests.

Like Richmond, Denver tried to solve financial problems and maintain a white voting base by maintaining population through annexation. In 1974, a constitutional amendment called the Poundstone Amendment fundamentally rendered annexation impossible. The condition of the city of Denver worsened.

By the mid-1980’s it was abundantly clear to the region’s business leaders that their communities had a shared economic fate, and it was not looking like a pleasant one.Katz and Bradley

Through a series of three votes, the Metro Denver area reconciled differences, built impressive infrastructure, and maintained the independence of surrounding counties.

The first vote levied a sales tax of 0.1% on a seven county district called the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District. When it passed in 1983, the coffers were empty. Now Denver has the 4th most visited zoo in the country, the highest paid membership to any nature/science museum in the country, and the second largest performing arts center in the country.

The important thing about the district, a third of all money raised went to projects outside of the city of Denver. A 0.1% sales tax on the Richmond region could help rid the city of the Meals Tax while guaranteeing worthwhile infrastructure and public goods. Animosity could be avoided by agreeing that a certain percentage of funding each decade would end up in the counties.

The second vote enabled Denver to annex a small part of Adams county in 1988 to build an airport. The big lesson for Richmond: taxes collected at the airport went to the city coffers but a certain percentage of jobs and “impact fees” were given to Adams county. With a project like a baseball stadium paid for by Metro Richmond, taxes directly from the stadium could be divided between the region while taxes from hotels, restaurants, and stores around the stadium could be reserved for the city.

The third vote occurred in 2004 when the region voted on a large transportation project called FasTracks. The construction is still in progress and the Great Recession didn’t help, but it offers another valuable lesson for Richmond. The construction happened almost exclusively north of Denver, but enjoyed broad support from the counties south of Denver. Leaders and residents were willing to look beyond their backyards and beyond the next few years.

The Metro Denver area benefitted from a series of vocal leaders who were willing to look at the big picture, but more importantly, they spoke to one another. What started in 1970s and 1980s with regular backyard barbecues and the occasional beer evolved into the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus in the 1990s. Today, Denver strikes a healthy balance between an independent city and counties with a regional look–and everyone is better off for it.

— ∮∮∮ —

Richmond unilaterally building shiny things is not the answer (Day #031). Regional cooperation on infrastructure spreads out the financial risk, but more importantly the votes, meetings, and construction strengthen community.

We are all Richmonders just as we are all Virginians and Americans. Animosity because of arbitrary borders, asymmetrical use, and antiquated trends caused by racism will not make this a better place to build lives. Regionalism is the only way for Richmond to escape its small Southern city label while reaching its full potential.

Love this idea? Think it’s terrible? Have one that’s ten times better? Head over to the 100 Days to a Better RVA Facebook page and join in the conversation.

- The use of resources without provision for their growth or sustainability. ↩

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 4 reader comments. Read them.