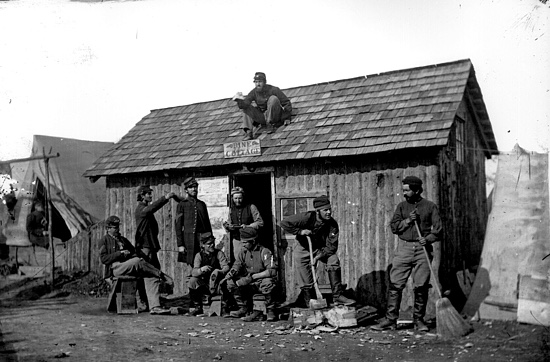

Civil War: Winter quarters

Cold and under siege, soldiers of the Civil War build some pretty…interesting winter quarters.

By December of 1864, soldiers outside Richmond and Petersburg started to settle into the routines of winter camp life. Despite a few efforts in early December by Union General Ulysses S. Grant to attack Confederate railroad supply lines into Petersburg, the cold weather, sleet, and snow forced both sides to lay low. It was a chance to rest up, regroup, and make plans for spring. For many soldiers, it was a chance to show off their structural engineering skills.

As the cold weather set in and it was clear they weren’t moving anywhere for a while, soldiers set about building their winter quarters. Working with the limited resources around them and without a lot of organization or oversight on behalf of leadership, it was a bit of a hodgepodge effort. Similar to your neighborhood during the holidays, you have some folks who toss up a few decorations and then a few who really go all out. Perhaps the winters quarters of 1864 could have inspired their own “tacky cabin tour”:

“I wish you could ride around & see how this great army of N. Va. is housing itself in its various departments for winter,” surgeon John Claiborne wrote to his wife in mid-October. “Here you may see a hut – such as nobody but a soldier ever conceived of – and there a tent of smallest dimensions with a chimney & door – and there a fellow – absolutely burrowing under the ground – and such contrivances for cooking and keeping dry & warm!” Trudeau, Noah Andre • _The Last Citadel_

The ingenuity of the soldiers in trying to add a little comfort to life in the trenches knew no bounds. Many soldiers wrote home bragging of the winter shelters they built, like Private William L. Phillips of the 5th Wisconsin, who wrote:

We have just finished a house 7 by 10 we packed the timber 1/2 mile on our shoulders it was heavy green pich pine a small piece of it is a load for any man… it is made of haves of pine logs about 8 inches through it is layed 5 feet high then covered with tent cloth the gable ends are closed up with boards the fire place and the door occupyse one end and the bunk acrost the other the bunk is made by driving 4 croches into the ground about 2 feet high then a cross peaces and little poles layed on these we covered with pine bows about 6 inches thick then covered with dry leaves this makes a captol bed right before the bed there is a low bench we can sit by the fire and lean our backs against the bed when we eat we spread a rubber cloth on the bed and turn right around on our seat and stick our feet under the bed and eat our hard tack and sow belly or beaf and drink our coffee contented as kittens. Greene, Wilson • _The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign_

Winter quarters were largely the same on both sides, although often the Confederates had less material to work with. Initially, many soldiers dug underground shelters to simultaneously protect them from both winter weather and potential Union artillery fire, but as the winter went on, more cabins similar to the Union style sprung up.

After several years of fighting, both armies had learned a thing or two about properly building a winter camp, so strict rules on hygiene were followed and large trenches were dug for the purposes of waste disposal. Sickness in camp continued to be an issue, but one that was better managed as the war dragged on.

With a lot of time on their hands and boredom setting in, soldiers entertained themselves in the usual ways. On one hand, gambling, drinking, and seeking the company of women (often of ill repute) were as popular as ever. On the other, the winter of 1864 saw a resurgence of religious activity among the soldiers with several informal chapels springing up among the winter quarters on both sides. Of course, drilling and marching still occurred on a regular basis to keep men fresh for fighting. Pickets were also constantly maintained to keep a watchful eye on enemy movements. Time spent on picket duty during those cold months could be pretty miserable–long nights with no fires to keep warm, always under the threat of a sniper’s bullet or mortar shell–something you definitely wanted to avoid if you could.

Picket duty did sometimes result in unusual activity involving the enemy. Occasionally, pickets on both sides formed an informal, temporary truce during which trades were made, banter was exchanged, and men bonded over their shared circumstances. Often as simple as agreeing to a cease fire during daylight hours, other times the encounters bordered on the ridiculous, given the circumstances:

Private Henry Houghton of the 3rd Vermont crossed between the lines to harvest firewood and encountered a Confederate on a similar mission. The enemies agreed to cut down the same tree together, the Rebel and Houghton hacking on opposite portions of the trunk. “After it fell I chopped down one side of the log and he the other, then we split it and he had one half and I the other, then we swapped hats and went back to camp and I am quite sure I wore that hat until just before the last review in Washington,” remembered Houghton. Greene, Wilson • _The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign_

Stories about encounters like this during the long siege at Petersburg (of which there are many) really highlight the shared humanity of the soldiers who fought in the war.

We’ll continue to tell the story of life in the winter camps over the next several weeks–everything from food shortages, desertions, to hearing about how the citizens of Petersburg fared during the siege. And as the winter weather subsides in 1865, we’ll learn about Grant’s attempts to jump start the spring offensive and Lee’s last ditch efforts to break through the siege.

The last five months of the war are upon us and there are plenty of stories left to tell!

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.