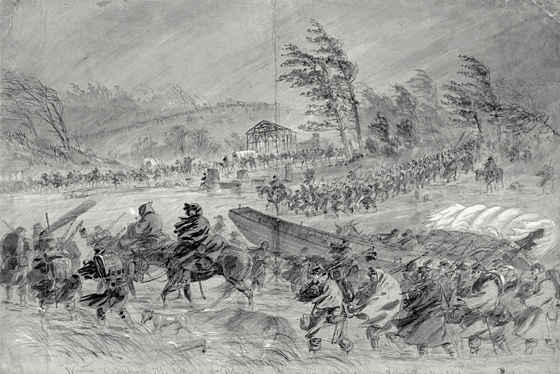

Civil War: The Mud March

Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s second attempt to strike at Richmond was easily thwarted–not by Confederate soldiers but by mud. Lots and lots of mud.

I have a feeling Union General Ambrose Burnside was anxious for a fresh start in January 1863. Ever since he replaced Gen. George B. McClellan as the commander of the Army of the Potomac in November of 1862, things hadn’t been going exactly as planned. The quick strike he arranged in December at Fredericksburg was thwarted by delays and ended in disaster: the Union suffered nearly 13,000 casualties fighting against a well-entrenched Confederate force in the heights south of the city. Despite the loss, Burnside was still eager to strike at Richmond and repair his damaged reputation.

Shortly after Christmas, Burnside devised a new plan to attack Richmond. He still needed to cross the Rappahannock, so this time he’d plan to cross the river upstream from Fredericksburg. He’d quickly assemble pontoons to cross the river and approach Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s left flank, drawing them away from their current positions and out into the open. The plan wouldn’t get underway until January 20th, with an easy four-hour march to the Rappahannock, at a crossing known as Bank’s Ford. Burnside’s order stated that the “great and auspicious moment has arrived to strike a great and mortal blow to the rebellion, and to gain that decisive victory which is due to the country.”

In true Ambrose Burnside fashion, things didn’t go exactly as planned. It started raining.

This wasn’t your average “you might need an umbrella” rainstorm. It was a nor’easter that caused a torrential downpour for two days. The rain quickly turned the dirt roads into a muddy nightmare. Burnside’s pontoons, artillery, and troops were all stuck in knee-deep mud. Determined to not let the storm stop him, Burnside continued to push his troops to the point of exhaustion.

The delays eliminated any element of surprise, allowing Lee to strengthen his left flank as he waited for Burnside to get “unstuck.” He positioned sharpshooters to harass Union soldiers at the river crossing. But that wasn’t the only harassment; Confederate soldiers took it upon themselves to write signs on the other side of the river poking fun at Burnside’s failure like “This way to Richmond!” and “Burnside’s Army Stuck in the Mud”.

On the third day, exasperated, demoralized, and still quite stuck, Burnside decided to issue a whiskey ration to the troops to help raise their spirits and encourage them to press forward. It had the opposite effect as drunken troops began brawling with one another. In some instances, entire regiments were engaged in fisticuffs.

Finally, on the fourth day, Burnside realized there would be no crossing the Rappahannock, and he cancelled the order. A Massachusetts soldier, Charles E. Davis Jr. wrote, “It is not an exaggeration to say, that before or after, there was seen no such state of demoralization as possessed a large part of the Army of the Potomac at the end of this foolish undertaking.”

In the end, Washington would agree with the men of the Army of the Potomac. On January 25th, Burnside was relieved of command and replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. If there was to be another attempt on Richmond, it would now have to wait until after winter.

— ∮∮∮ —

A note on weather & the Civil War

By Dan Goff

The first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Joseph Henry, was a fan of the weather. Beginning in 1847, he established a weather observation network that included more than 600 observers, who submitted observations by telegraph and mail, by the time war broke out in 1861. Unfortunately the war brought that network to an abrupt halt, as communication was lost with the observers in the South and communications for the Union armies and other traffic received higher priority than weather observations. Richmond’s own Civil War expert, Douglas Southall Freeman, lamented this lack of detailed weather info in a talk he gave to some Civil War enthusiasts not long before his death: “I beseech you, give us what we do not now have but long have needed, namely, a meteorological register of the War Between the States.”

Historian Robert Krick collected a number of first-hand weather reports over the course of the War in his book “Civil War Weather in Virginia.” About the Mud March, one colonel from New York wrote that the 21st was “about as stormy a day it is possible to get up.” Another of the Union soldiers stuck in the mud observed: “The Rebs across the river stuck up a board with the words ‘Burnside stuck in the Mud’ in large letters.” One Virgina soldier located south of Fredericksburg wrote on the 23rd “Rain – rain – rain – nothing but rain from morning until night, and from night until morning.”

While no direct observations from the field are available in the record, observations taken by Rev. C. B. Mackee in Georgetown place temperatures over the course of the Mud March in the 30s and low 40s, with nearly two inches of rain recorded — all in all, not that different from what we saw in Richmond just a couple of weeks ago.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.