Civil War: The Dahlgren-Kirkpatrick Raid

Of all the attempts to attack the city of Richmond during the Civil War, none were as audacious as the Dahlgren-Kirkpatrick raid in March of 1864.

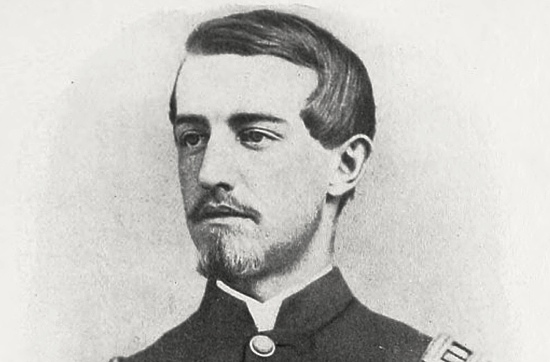

It all began at a party in late February, where two Union officers met for the first time. Union General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick was known for both his daring and recklessness in battle, earning him the nickname “Kill Cavalry,” due to his willingness to put his men in harm’s way. Colonel Ulric Dahlgren was young, only 22-years-old, but battle-tested. In the Battle of Gettysburg, Dahlgren had been wounded and lost his right leg, and now walked with a wooden leg. At the party, Kilpatrick told Dahlgren of his plans to attack the Confederate capital.

Unlike previous Union attempts on Richmond, Kilpatrick’s plan called for a quick surgical strike instead of a grand assault on the city. Using the element of surprise, Kilpatrick would send nearly 4,000 cavalry troops to free Union prisoners of war on Belle Isle and damage critical Confederate infrastructure. Dahlgren, the son of a well-known rear admiral in the Union navy, was eager to prove himself and signed on to participate in the raid. Kilpatrick would split his cavalry force, sending 3,500 to attack Richmond from the north, while Dahlgren would lead a small cavalry force of about 500 in a wide sweeping motion around to attack from the less-defended southern side of the city.

Both men were very confident in their plan, although admittedly neither had planned for a way to arm, feed, or transport the Union prisoners once they’d been freed. Nonetheless, Kilpatrick made sizable bets with superior officers regarding the success of the mission. Dahlgren boasted to his father in a letter, “…there is a grand raid to be made, and I am to have a very important command. If successful, it will be the grandest thing on record; and if it fails, many of us will ‘go up.'”

The plan was set in motion after nightfall on February 28th. The following afternoon, Kilpatrick’s forces arrived in Beaver Dam, VA and began tearing up rail lines and burning buildings as they continued south down the Brook Turnpike (today’s Brook Road). They arrived at the outer defenses of Richmond on the morning of March 1st, and a pitched battle began against Richmond’s home guard. Kilpatrick’s troops set up a line of battle on Taylor’s Farm, located near today’s Westbrook Road in Bellevue. After several hours of fighting, Kilpatrick was nervous–where was Dahlgren? He hadn’t heard any word from him and he began to get the sense that he was in this fight alone. Dahlgren had not yet entered the city from the south.

So where was Dahlgren? That story gets a bit more complicated.

Dahlgren’s first few days were similar to Kilpatrick’s: burning buildings, destroying railroad lines, and heading towards Richmond. As he neared Richmond, he stopped at the plantation homes of two important government officials, Confederate Secretary of War Alexander Seddon and former Virginia governor Henry Wise. Seddon was away in Richmond at the time, but Wise was home at the time of Dahlgren’s arrival and escaped on horseback undetected. Wise was able to make it to Richmond and warn the government about Dahlgren’s approach from the west.

Dahlgren still had yet to cross the James River, a critical part of his surprise attack. He used a local guide, a freed slave named Martin Robinson, to help him find a point where his cavalry could ford the river. Robinson led them to a point in the river near today’s River Road just a few miles before you reach Goochland County. However, the river levels were higher than usual and it was not possible to cross. Frustrated and angry, Dahlgren suspected Robinson misled them intentionally and dispatched him in an unexpectedly brutal way, hanging him from a tree with the reins of his own horse. Now without a guide to cross the river, Dahlgren decided to proceed along the north bank of the river toward Richmond instead. This, along with Wise’s advance warning, would be his undoing.

Back on the north side of the city, Kilpatrick was still engaged with Confederate forces along the city’s outer defenses on Brook Road. He feared the arrival of more reinforcements and with no word from Dahlgren, he decided to call off the attack and fall back to safer ground on the peninsula. Now Dahlgren, with a force of less than 500 cavalrymen, was truly alone.

The next day, Confederate forces headed out from Richmond to intercept Dahlgren’s raiders. Meeting strong resistance, Dahlgren quickly realized the futility of the attack and tried to find his way north and out of harm’s way. Harm, unfortunately found him, in the form of an ambush where he was killed by cavalry from the 9th Virginia. Many of the soldiers under his command were captured, imprisoned in the very place they were sent to liberate.

Kilpatrick’s early withdrawal ensured he would live to fight another day. He would head south to join Sherman on his infamous “march to the sea” campaign. When questioned about the reckless nature of “Kill Cavalry” Kilpatrick, Sherman replied “I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool, but I want just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition.”

The story doesn’t end there, however. In the aftermath of Dahlgren’s death, a document was found on his person that shocked the Confederacy and revealed a conspiracy that is still debated about today. We’ll talk more about this document in the next column.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.