Civil War: Prison break

Of all Richmond’s Civil War stories, this story is the one that most truly shows the determination, ingenuity, and courage of the Union prisoners who spent time incarcerated in the Confederate capital.

At the outset of this RVANews Civil War project back in (whoa!) 2011, I wrote down all my favorite stories of the war despite the fact that in some cases, they were three or four years away. This is one of those stories. I wasn’t sure if I’d still be writing this column by the time these stories would be written, and I’m quite happy to still be sharing them with you.

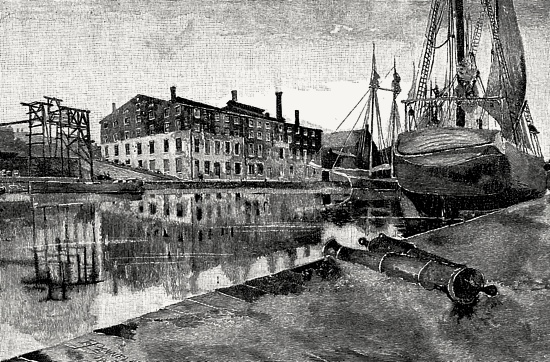

Of all Richmond’s Civil War stories, especially those told of the city’s prisoner population, this story strikes me as the one that most truly shows the determination, ingenuity, and courage of the Union prisoners who spent time incarcerated in the Confederate capital. Libby Prison, a three-story brick warehouse located in Shockoe Bottom, was the prison where Union officers were held. On the morning of February 10th, 1864, guards at the infamous and “inescapable” Libby Prison found 109 prisoners absent during the morning roll call. At first, prison officials assumed that the Union soldiers were playing a trick, but after several recounts, it was clear that some prisoners had gone missing.

The calling of the roll consumed nearly four hours, and out of the one thousand and fifty odd officers confined in the prison the day previous, one hundred and nine were found to be missing. At first it was suspicioned that the night sentinels had been bribed, and connived at the escape; and this suspicion received some credence from the statements of the Yankee officers, who said the guards had passed them out by their posts. The officer of the guard, and the sentinels on duty the night previous, were accordingly placed under arrest by Major Turner, and after being searched for money or other evidences of their criminality, confined in Castle Thunder, in order that further developments might either establish their innocence or fix their guilt upon them. Charleston Mercury, 2/16/1864

The idea that the Union prisoners could escape without the assistance of guards seemed impossible, and yet, that’s exactly what happened.

It all began months earlier because of the collaboration of two men: Col. Thomas E. Rose and Major A.G. Hamilton. The two men shared a room and were both intent on finding a way to escape Libby Prison. Major Hamilton described their thought process and initial steps:

“We had both arrived at the conclusion that there was only one way for us to get out of the prison, and that was to dig out. This conclusion was reached after the basement kitchen had been closed. After considerable deliberation it became a settled fact that the tunnel would have to be dug from the east basement, but how to get into the basement was the next serious question that stared us in the face. All access to it had been closed and the stair and hatchways securely nailed. In the front of the kitchen we were then occupying there was a fire-place with two cook stoves in front of it, with a large pile of kindling wood. A hole through the brick wall at this place would give us the access that we desired. I borrowed a knife from Lieut.-Colonel Miles and one night when nearly all the prisoners were sleeping I carefully moved one of the stoves aside, and with the aid of the knife dug the mortar from the bricks. Thus the bricks were loosened, carefully taken out, and our access to the cellar was made. Then a board was ripped from the top of a bench and with its aid we went down into the black basement, amid the hurrying, scurrying, squealing rats.”

The basement kitchen had been closed due to frequent flooding and a severe rat infestation. The room itself became known to prisoners and guards alike as “Rat Hell”. It would be the base of operations for the tunnel escape.

The small group of men who dug the tunnel worked in nearly continuous five-man shifts for weeks, laboring in almost complete darkness and surrounded by scurrying rats. The floor of the basement room was covered in straw which they used to cover up the tunnel entrance and excess dirt. Confederate guards would occasionally look in the basement room on their rounds, but the men could hide in the straw, and the guards had no interest in lingering in “Rat Hell” any longer than they had to. Two initial attempts at tunnels failed, but they finally nailed it on the third attempt–opening up a hole in the dirt floor of a tobacco shed about 60 feet away from the prison. On the night of February 9th, 109 prisoners would crawl through the hole in the fireplace, down into the basement, and out through the tunnel to freedom.

Freedom from Libby Prison was one thing–getting out of the heart of the Confederate capital without detection was another thing entirely. The men slowly left the shed in groups of one or two at a time, and managed to blend in and not raise any alarms. The men’s dirty Union uniforms and greatcoats went unnoticed in the dark of night. Men scattered in all directions, but most headed toward the east of the city–familiar ground to many who fought during the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. None were captured in the city that night.

Meanwhile, the following day, the Confederates were still at a loss for how the escape occurred in the first place. Union officers who remained behind in the prison had the foresight to replace all the bricks in the fireplace and made it very difficult for prison guards to determine the escape route. Finally, it was discovered.

Lieutenant La Touche and Major Turner made a thorough inspection of the basement of the prison, which slopes downward from Cary street towards the river dock. This basement is very spacious and dark, and rarely opened except to receive commissary stores. A stairway leading down from the first floor, has long ago been boarded over and there was no communication from above. The wall masonry of the basement, near the front of the building, commences at least ten feet below the level of Cary street. At the base of the east wall, and about twenty feet from the Cary street front, was discovered a tunnel, the entrance to which was hidden by a large rock, which fitted the aperture exactly. This stone, rolled away from the mouth of the sepulchre, revealed an avenue, which it was at once conjectured led to the outer world beyond. A small negro boy was sent into the tunnel on a tour of exploration, and by the time Major Turner and Lieutenant La Touche gained the outside of the building, a shout from the negro announced his arrival at the terminus of the subterranean route. Richmond Examiner, 2/11/1864

The route now discovered, the city guard and citizenry mobilized to capture the escaped prisoners. However, nearly 17 hours had passed since the initial escape began. This head start allowed 59 of the 109 prisoners to successfully cross Union lines to freedom. Unfortunately, most of the remaining number were recaptured, including Col. Rose, who was captured by a Confederate picket just a few short miles from Union lines. Two men died in the escape, drowning in the James River.

Fortunately for Col. Rose, the Confederates couldn’t stomach the idea of the escape’s mastermind being held at Libby and potentially hatching new schemes or instigating others to take flight, so they promptly held a prisoner exchange and sent him back north in April. Rose rejoined his unit, the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry, and fought through the remainder of the war. After the war, Rose was reticent to talk about his involvement in the prison escape and went so far as to say “I do not want to be distinguished, especially if distinction must come through so much pain and sorrow as did the little I gained from the event in Libby.”

The event would go down in history as the largest prison escape of the Civil War. Even though many of the 109 prisoners were recaptured, the event shook the citizenry of Richmond and helped to improve morale within Libby Prison for the remainder of the war. Just a short month later, another attempt at freeing Libby’s prisoners would have an even more dramatic effect on the city, but that’s another story that you’ll hear about soon.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.