Civil War: One Last Chance for Peace

A Union rock meets a Confederate hard place (or was it vice versa?) as everyone agrees that peace would be great, but no one can figure out how to do it.

In the early weeks of 1865, Confederate leaders in Richmond surely must have been taking inventory of their increasingly bleak situation. A growing Federal force led by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had Richmond and Petersburg in a vice grip – a siege that threatened to break the back of the Confederacy. Meanwhile, to the south, Gen. William T. Sherman had just completed his “March to the Sea”, a campaign of devastation across Georgia that led to the capture of Atlanta and Savannah.

If there was ever a time to test the waters for a peaceful end to the war, this was it. A successful military solution seemed farther and farther out of reach for the flailing Confederacy.

Surprisingly, the first overtures to discussing peace came from within the Union. A discussion between New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley and Union Maj. General Francis P. Blair led to a request to President Abraham Lincoln to attempt a peace conference. The two offered to send Blair, a well-known conservative Republican, to Richmond for an informal (and secret) meeting with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Blair would act as an intermediary between the two presidents, testing the waters for a possible meeting to discuss an end to the war. Lincoln, anxious to end the war, granted Blair permission to cross enemy lines and meet with Davis in Richmond. The first meeting took place in Richmond on January 12th.

After the meeting, Blair returned to Washington with a note from Davis offering to send Confederate delegates to discuss a way to “secure peace to the two countries.” After meeting with Lincoln on the 18th to convey Davis’ offer, he was sent back to Richmond with a letter from Lincoln that read “I have constantly been, am now, and shall continue ready to receive any agent whom he, or any other influential person now resisting the national authority, may informally send to me, with the view of securing peace to the people of our one common country.” It’s important to note Lincoln’s wording in his response. Even in pursuing peace with Davis, he was not willing to let his acknowledgement of the Confederacy go uncorrected.

Davis selected three delegates to represent the Confederacy: Vice President Alexander Stephens, Assistant-Secretary of War John A. Campbell, and Confederate senator R.M.T. Hunter. In late January, the three men left Richmond and headed to General Grant’s headquarters at City Point, Virginia. Upon their arrival, Gen. Grant, who had largely been left out of the negotiation process, provided them with lodging on one of the more comfortable passenger steamships in the harbor. For several days, the delegates awaited for the federal representatives to arrive. During that time, Grant played the role of gracious host, but intentionally kept his distance, later writing in his memoirs:

I saw them quite frequently, though I have no recollection of having had any conversation whatever with them on the subject of their mission. It was something I had nothing to do with, and I therefore did not wish to express any views on the subject. For my own part I never had admitted, and never was ready to admit, that they were the representatives of a government. There had been too great a waste of blood and treasure to concede anything of the kind. As long as they remained there, however, our relations were pleasant and I found them all very agreeable gentlemen.

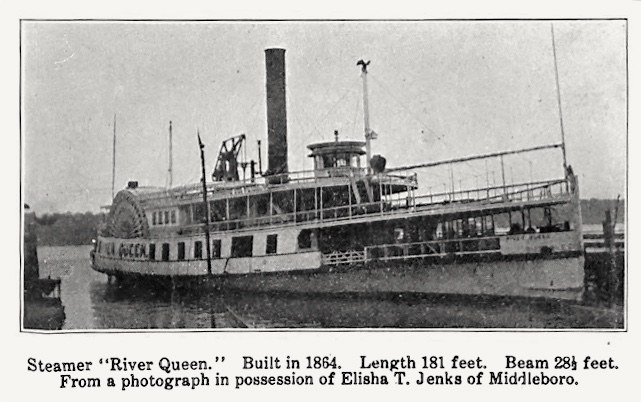

After a few days, Stephens, Campbell, and Hunter left City Point and headed to Hampton Roads, where they boarded the steamship River Queen. Instead of meeting with delegates from the Union, they were greeted by none other than Abraham Lincoln himself, who was joined by Secretary of State William H. Seward. The men exchanged pleasantries (Lincoln and Stephens were actually acquaintances in their pre-war political careers) and got down to the business of negotiation.

The meeting lasted about four hours, and the topics ranged from armistice to the question of slavery and reconstruction. The Confederate delegates were under instruction from Davis not to consider any offers for peace that didn’t include recognition of the Confederacy as a separate country. Lincoln, on the other hand, was unwilling to consider any scenarios that didn’t involve the southern states returning into the fold of the Union. Rock, meet hard place.

Just days before, Lincoln had signed the 13th amendment of the Constitution, abolishing slavery. Lincoln expressed his desire for the South to follow suit, but discussed the idea of possibly compensating southern slaveowners who freed their slaves. Seward went so far as to suggest that, if southern states returned to the Union, perhaps they could successfully overturn the 13th Amendment altogether.

Admittedly, this was a bit of a record-needle-scratch “Wait, what?!” thing for me. Lincoln and Seward had both just worked so hard behind the scenes to get the 13th amendment passed through Congress, I have to believe this was mostly just posturing from Seward. But then again, I wasn’t in the room, and no one was taking notes at the time.

Ultimately, the Confederacy was playing poker with a pretty weak hand. It was clear to both parties that a military victory for the Union was within reach, so the only motive Lincoln had for compromise was the desire to end the war sooner. In the end, he wasn’t willing to compromise on his core beliefs – peace could not be achieved until the Southern states agreed to return to the Union and abolish slavery. Without these things, there would be no deal. The Confederate delegates were unwilling (and unauthorized) to agree, so they returned to Richmond empty-handed.

While a few more minor diplomatic efforts (mostly the exchange of letters) took place in the final months of the war, Lincoln and Davis remained committed to their beliefs and a negotiated peaceful end to the war remained out of reach. The Civil War would soon come to a close, but only with the destruction of the Confederacy and months of more bloodshed on both sides.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.