Civil War: Endings and beginnings

Here it is, the end of a very long and very bloody road. Thus concludes our four-year series commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War and its impact on Richmond.

It’s here. The end of our four-year sesquicentennial project, which explored the Civil War’s impact on Richmond in historical real-time. Recapture the magic from day one. And if you have a sec, drop @heyitsphil a line on Twitter (or leave a comment here) telling him how great you think he is! I mean, a four-year project, guys!

As dawn was breaking on the morning of April 26th, 1865, a dying John Wilkes Booth lay paralyzed on the front steps of the Garrett farm, located outside Port Royal, VA–a scant 50 miles northeast of Richmond. Just ten days after assassinating President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in an attempt to ignite a Confederate resurgence, Booth had become the focus of one of the largest manhunts in U.S. history, one that ended inside of a burning tobacco barn with a bullet through the neck that severed Booth’s spine. As he lay dying, realizing that history wouldn’t remember him as the hero he’d imagined himself to be, he muttered his last words, “Useless, useless.”

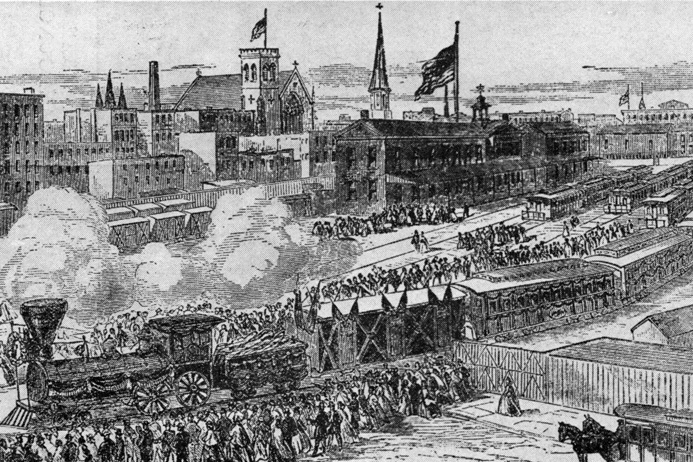

Meanwhile, further north, a funeral train carrying the coffin of Abraham Lincoln traveled from Washington, D.C. to Lincoln’s home state of Illinois for burial. Along the train route, huge crowds gathered to pay their last respects to the fallen president. In cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, the coffin was removed from the train and placed on a carriage for a funeral procession through the city, often ending with a public viewing of Lincoln’s body lying in state. The Philadelphia Inquirer described a scene that was repeated at every stop along the train route:

Half a million of sorrow-stricken people were upon the streets to do honor to all that was left of the man whom they respected, revered and loved with an affection never before bestowed upon any other, save the Father of his Country. Universal grief was depicted on the faces of all. Hearts beat quick and fast with the throb of a sorrow which they had never experienced. Young and old alike bowed in solemn reverence before the draped chariot which bore the body of our deceased, assassinated president. The feeling was too deep for expression. The wet cheeks of the strong man, the tearful eyes of the maiden and the matron, the hush which pervaded the atmosphere and made it oppressive, the steady measured tread of the military and the civic procession, the mournful dirges of the bands, the dismal tolling of the bells and the boom of the minute guns, to more than it is possible for language to express.

On that same day in April, Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston met with Union Gen. William T. Sherman at a farm called Bennett Place in Durham County, North Carolina and agreed upon surrender terms. The terms, which were the same offered Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee a few weeks earlier, led to the surrender of nearly 90,000 soldiers, the largest surrender of Confederate forces in the war. Now that both Lee and Johnston’s armies were out of the fight, it would only be a few weeks before the remaining Confederate armies in the field laid down their arms as well.

Back in Washington, things were contentious to say the least. Lincoln, who had a good handle on the “Radical Republicans” within his own party, was replaced by his vice president, Democrat and southerner Andrew Johnson. As president, Johnson struggled to implement Lincoln’s “with malice toward none” approach to reuniting the southern states with the Union. Republicans advocated for taking a harsher stance with the former Confederates and proposed laws that upended the aristocratic hierarchy of the south.

On the other side, Southern states quickly set in motion repressive laws that restricted the freedoms of its black population. State laws called “Black Codes” forbid interracial marriage and set the stage for the segregated south. We’ll never know how Reconstruction would have been different if Lincoln had lived to see his vision of reconciliation come to fruition, but it’s easy to imagine how his leadership and influence could have led to a better outcome. The decisions made during this fragile and tumultuous time after the end of the Civil War would echo for generations throughout our country–and still have impacts today.

— ∮∮∮ —

This is my last column for this four-year series documenting events in Richmond 150 years ago during the Civil War. I had no idea where this would lead when I started it, but it has been one hell of an interesting project and I’m so grateful that the fine folks of RVANews asked me to take it on. My hope is that I’ve helped bring an important part of this city’s history to life–and showed how much Richmond was shaped by the events of the Civil War. I also hope that I made Richmond’s history a little more accessible to people who don’t think touring battlefields is necessarily a fun way to spend a weekend.

Like it or not, the Civil War built and shaped this city. And as long as there are still statues standing on Monument Avenue, we’ll continue to be defined by it. Even now, despite so much progress, our city is still divided along racial lines. Debates over how we acknowledge our dark past as a center for the slave trade are on the front page of our newspapers. Protesters waving Confederate flags and signs still spend their Saturdays out in front of our state art museum. But we can make Richmond so much more than its history–even now, we are finding brand new ways to define ourselves. It’s a really exciting time to be here.

I love this city–who knows what the next 150 years will bring?

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 4 reader comments. Read them.