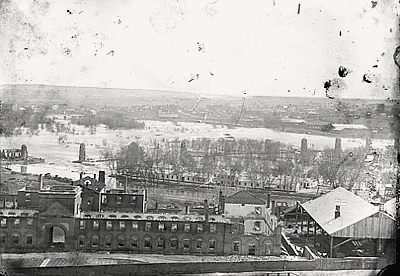

Civil War: An Explosion rocks Brown’s Island

On March 13th, 1863 a deadly explosion rocked Brown’s Island.

On Friday March 13th, 1863, eighteen-year-old Mary Ryan was at work at the Confederate States Laboratory on Brown’s Island. The small ammunition factory had several hundred employees, most of whom were young women between the ages of twelve and twenty. The work, which often required small hands, was vitally important to the Confederate war effort, which suffered often from shortages in the supply of ammunition.

The C.S. Laboratory was divided into six departments, and Mary Ryan worked in the last one. Seated at the end of a table with a handful of other employees, she was filling friction primers–the devices used to ignite gunpowder inside a cannon. This was dangerous work. In fact, the superintendent Captain Wesley N. Smith had reminded her of that during his routine inspection of the facility just fifteen minutes prior. Shortly after 11:00 AM, Mary noticed that the primer had gotten stuck and so she struck the table three times to dislodge the primer. Upon the third strike, the primer ignited and an explosion sent her flying upwards. The first explosion ignited other materials in the room, causing a second, much-larger explosion that destroyed the building completely.

The Richmond Examiner described the initial reactions around the city:

A dull, prolonged roar in the direction of Brown’s Island, across the James river from the foot of Seventh street, startled that portion of the city and directed attention to the island, on which is located the Confederate Laboratory works, for the manufacture of percussion caps and gun cartridges. – But similar sounding explosions, arising from the trial of ordnance at the Tredegar Iron Works, had been daily heard in that neighborhood, and it was some minutes before a dense smoke arising from the island apprised the citizens of the true cause of the explosion…

…A tide of human beings, among them the frantic mothers and kindred of the employees in the laboratory, immediately set towards the bridge leading to the island, but the Government authorities, soonest apprised of the disaster, had already taken possession of the bridge, and planting a guard of soldiers, allowed passage to none except the workmen summoned to rescue the dead and wounded from the ruins. Richmond Examiner, 3/14/1863

The scene awaiting the workmen at the scene of the explosion was truly horrific:

Some ten to twenty were taken from the ruins dead, and from twenty to thirty still alive, but suffering the most terrible agonies, blind from burns, with their hair burned from their heads, and the clothes hanging in burning shreds about their persons. Others less injured ran wailing frantically, and rushing wildly into the nearest arms for succor and relief. Mothers rushed about, throwing themselves upon the corpses of the dead, and the persons of the wounded.

The immediate treatment of the burned consisted in removing their clothing and covering the body thickly with flour and cotton, saturated with oil; chloroform was all administered. The sufferings of the wounded were alleviated by these means in the interval between their rescue and removal to their homes, or General Hospital No. 2, where many were taken. The returning ambulances carrying the sufferers were besieged by the friends and relations of the employees, and children clamored into the vehicles crying bitterly in their search after sisters and brothers. The distress among friends was aggravated by the fact that it was utterly impossible to recognize many of the wounded on account of their disfigurement, except by bits of clothing, shoes. Richmond Examiner, 3/14/1863

As you can imagine, the medical science around treatment of burns and prevention of infection at this time was limited at best. Most of those wounded would die in the weeks to come.

As the days following the event passed, more eyewitness accounts emerged. Some gave accounts of girls with their clothing on fire running into the James River to try to extinguish the flames. One such girl, Martha Burley, drowned in her attempt. Another girl whose clothes were on fire very nearly caused a much larger explosion when, in a blind panic, she ran toward another laboratory building where gunpowder was stored. A quick-thinking employee grabbed the girl and put out the flames just in the nick of time.

For a city that already knew and understood suffering during wartime, this was a new level of tragedy for Richmond. The city would spend the next several weeks awaiting news of those injured in the explosion and making efforts to raise money to support their care.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 2 reader comments. Read them.