Civil War: A tightening grip on Richmond

150 years ago, the siege of Petersburg continues, despite the best efforts of the Union General Ulysses S. Grant.

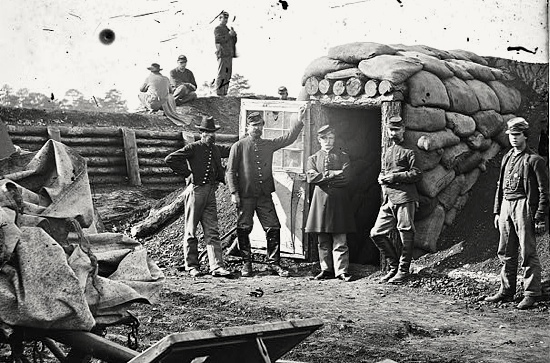

Civil War: A Tightening Grip on RichmondBy October of 1864, the siege of Petersburg was into its fourth month. During the summer, the Union army had focused on cutting off Petersburg (and thus Richmond) from key Confederate supply lines located west of the city. But by October, a handful of roads and railroad lines still delivered supplies and reinforcements to the Confederate defenders manning the trenches. Union General Ulysses S. Grant had made some progress by summer’s end, but had yet to cut off the city completely, which he knew could bring the war to a quick close.

One reason for the Union’s slow progress that summer was the quick movement of troops in Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Every time an assault was imminent, Lee concentrated his meager troops to counter the Union blow. In September, Grant had a plan to deliver a one-two punch to Lee’s forces. He would send troops under Gen. Benjamin Butler along the far right flank to coordinate a surprise attack north across the James River, threatening Richmond. Then, once Lee reallocated his troops to fortify his Richmond defenses, he would send another assault against the far left flank to the west of Petersburg. By attacking the Petersburg and Richmond defenses simultaneously, he felt he had the best chance to dislodge the Confederates and take both cities. If either one fell, it would be simple to take the other.

The first assault started at dawn on September 29th. Union forces under Butler attacked at a place called New Market Heights and later at Fort Harrison. As with any attack on a fortified position, losses were heavy, especially among United States Colored Troop (U.S.C.T.) units, who played a pivotal role in the charge that day. Northern newspapers were quick to praise them for their courage:

“The behavior of the negro troops…was of the most gallant character,” William H. Merriam of the Herald affirmed. “Who dare say, after this, that negroes will not fight?” the Times’s Winser asked his readers. “To-day their praises have been on every tongue, and too much cannot be said in appreciation of their courage.” Trudeau, Noah Andre.The Last Citadel. pg. 208

The U.S.C.T. was finally getting a chance to show their mettle in the last year of the war. As the fighting continued, Union soldiers took control of the poorly-defended Fort Harrison. From there they continued both north and south of the fort in an attempt to capture more of the rebel defensive lines, but were repulsed by Confederates who rallied to the defense. Satisfied with taking the fort, and realizing the strategic benefit of its location, Union forces dug in there and began fortifying it for their benefit. The following day, Confederate forces, commanded by Lee himself, attempted to take Fort Harrison back, but were unsuccessful. The fort would remain in Union hands for the remainder of the war.1

Meanwhile, just as Lee was counterattacking at Fort Harrison, things were heating up on the far left flank west of Petersburg. Just as Grant expected, Lee had pulled several reserves from the defensive lines there to help shore up the fight outside of Richmond. Still, there were rebels to contend with, specifically at a defensive point known as Fort Archer, where the two armies clashed. Herald correspondent L.A. Hendrick was an eyewitness to the charge:

“The order being given to charge, the skirmish battle lines soon advanced across the open ground. The charging column pressed steadily, earnestly, persistently forward… ‘A commission to him who first mounts the parapet of that redoubt,’ shouted Col. Welch of the Sixteenth Michigan, to his men. He was the first to mount the parapet, where he waved his sword. In an instant a rebel bullet penetrated his brain, and he lay dead…” Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel. pg. 213

Soon after, the Confederates fell back, yielding the fort to the Federals. Over the course of the next several days, the Union forces continued to try to push their flank further to threaten critical supply routes, but were repulsed by a renewed presence of Confederate reinforcements. On both flanks, Confederates simply dug into new positions, pushed back a little further, but still unbroken. If Grant thought he could deliver the crushing blow before winter, he was surely disappointed. The fighting around Petersburg and Richmond in 1864 continued to be a battle of incremental gains and losses–a “monumental” victory would remain elusive for quite some time.

- As a side note, for those interested, Fort Harrison is one of the best-preserved Civil War sites near Richmond and well worth a visit. It’s located yards away from Hadad’s Lake, most recently known as the home of the Gwar-BQ. An afternoon spent listening to GWAR and exploring old Civil War forts–what could be more Richmond? ↩

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

Notice: Comments that are not conducive to an interesting and thoughtful conversation may be removed at the editor’s discretion.

Thanks for writing this article.

It is in the Overland Campaign and at Petersburg that Lee’s brilliance really shines. He was grossly outnumbered and outequipped and by the late fall of 1864 his army was starving. Grant was able to throw large numbers at Lee’s dwindling forces, yet Lee was able to forecast those attacks and have reserves stationed close by. He shifted forces constantly, propping up one segment of the front at the expense of another, and almost always able to ensure sufficient forces were present to prevent a break through. By this stage of the war, his men called him the “Ace of Spades” since he made them get their shovels and dig trenches constantly — it was this preparation that enabled them to stay in the field as long as they did.

Good article which sheds light on a little known episode of the Siege of Petersburg. I respectfully disagree somewhat with JSmith’s assessment.

Lee continued to be a good general, but his officer corps had been decimated from corps command down to company command. Captains were in charge of regiments, colonels in charge of brigades, etc.

In addition, the Confederate command situation north of the James River was fragmented. Richard Ewell was in command of the troops from the Department of Richmond, while Field was in command of his division from the First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia. In the end, Fort Harrison was barely guarded by some artillerists, part of Johnson’s TN Brigade, and Virginia reserves. It is what allowed the Army of the James to take what was a formidable work rather easily. Lee wasn’t present in person and it took time to get more ANV brigades to the scene. By then it was too late.

On September 30, Lee took charge in person, but the piecemeal assaults by various brigades of Hoke’s and Field’s divisions ended in a bloody repulse.

Lastly, I do not recall ever reading about Lee being called “King (not Ace) of Spades in 1864. That sobriquet was applied in 1862, when Lee’s decision to fortify the lines east of Richmond so he could launch his massive and audacious assaults during the Seven Days.

Thanks. I didn’t discuss his other officers, and thank you for making that point. Captains in charge of regiments were not commonplace, at least as far as I have seen. Colonels in charge of brigades were commonplace, but that was true throughout the war.

You are right about King of Spades. Thanks.