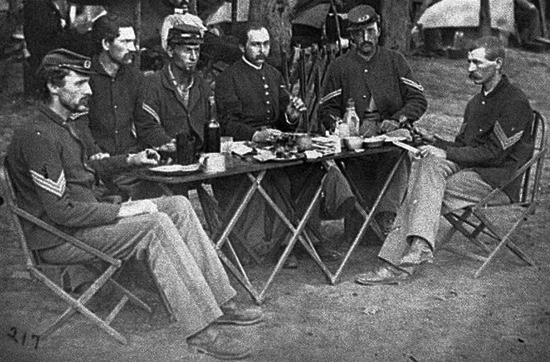

Civil War: A New Year’s Day “feast”

150 years ago, the holidays were a deluge of rain and mud. Sound familiar? Oh well, at least we won’t have New Years stuck in the trenches of Petersburg.

Let’s face it. It sucks to be away from family and friends during the holidays. Whether it’s due to travel complications, your work schedule, or it’s 1865 and you’re stuck in a cold, miserable, muddy trench outside Petersburg surrounded by your fellow dirty soldiers–it’s no fun. For both Union and Confederate soldiers alike, the holidays and thoughts of home just compounded what was already a pretty bleak situation.

‘Tis Christmas. Yet how differently do we feel this damp morning, huddled around our camp-fires, from what we were wont to enjoy four years ago — before fanaticism had driven us from our pleasant homes to battle for freedom’s cause. However, we do not complain. Letter to the Editor, Richmond Dispatch • 1/2/1865

As the holidays neared, citizens of Richmond decided to band together to do something to help the Confederate troops. Their plan was to coordinate a large Christmas feast (which later turned into a New Years feast) for the soldiers in order to thank them for their months of hard work protecting the Confederate capital during the Petersburg siege. News of the charitable effort reached the Richmond newspapers, who quickly helped to promote it for several weeks in order to drive donations of food. Donations poured in from across the city. Word soon reached the soldiers, and the Confederate camps were abuzz over the impending feast. South Carolinian John Coleman wrote in his diary:

Christmas Day, and very very cold. Have been moving about some of late, but are again in our old quarters, We have had very unpleasant weather for several weeks. The rain had almost washed us away. The whole country around about here appears to be under water it is almost impossible to get about at all. All military movements will have to stop until the roads improve, It is said that Ladies of Richmond intend giving us a New Years dinner hope it may prove true would like right will to get something good to eat.

The feast would take place on January 2nd, 1865 since New Year’s Day fell on a Sunday. In Richmond, the days leading up to the event was a flurry of cooking and preparation:

This is the last day in which to prepare for the dinner intended for the soldiers of General Lee’s army on New-Year’s day. The collection of cooked and uncooked fowls and meats, up to yesterday afternoon, at the Ballard House, was such as but few persons ever witnessed before, and yet, in the opinion of those in charge, a further supply will be needed. The Treasurer, Mr. John J. Wilson, calls for a continuance of contributions in money and provisions. Richmond Dispatch • 12/31/1864

That note about “a further supply would be needed” is a critical one. It’s not clear if the organizers significantly underestimated the amount of food needed to feed an entire army, had trouble getting enough donations, or had some mismanagement from suppliers along the way, but the fact of the matter is that when it came time to distribute the feast to the soldiers, there was barely enough for a bite of food per soldier. Coleman wrote in his diary a few days later:

The long talked of Christmas dinner has come at last. Three turkeys, two ducks, one chicken and about ninety loves, for three hundred and fifty soldiers. Not a mouth full apiece where has it all gone too, where [did] it go? The commisser or quarter masters no doubt got. May the Lord have mercy on the poor soldiers.

There are many similar stories of discontent from the New Year’s dinner in soldiers’ diaries and letters home in January of 1865. It’s hard to imagine how crushing this must have been for the soldiers, who had been subsisting on substandard rations and anticipating this event for weeks. A correspondent for the Dispatch wrote “The New Year’s dinner has come and gone, or rather, gone, without coming” (City Under Siege • Mike Wright) If Confederate morale was struggling before this, they’d just found a new low point.

Richmonders were quick to try to distance themselves from the debacle, and the Richmond Enquirer was quick to backpedal from any involvement:

The manager of the Enquirer desires to state to his friends in the army that he had nothing to do with the distribution of the New Year’s Dinner. Richmond Enquirer • 1/3/1865

Perhaps the failed New Year’s dinner was a fitting start to 1865 for the Confederate capital. The Confederacy only had a few short months left to live, and each month would bring dwindling resources and ever-decreasing odds against a larger, more-powerful foe. Safe for the short term in the last remaining weeks of cold weather, things weren’t going to hold much longer in Petersburg. On the other side of the trenches, General Ulysses S. Grant and his better-fed and better-equipped Union army anxiously awaited the opportunity to resume fighting and bring the Civil War to a decisive close.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.