Civil War: A Breakthrough at Fort Stedman

In March of 1865, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee needed a miracle. And a bloody, tide-turning miracle he got…for about four hours. Then that tide turned right back around. It’s happening, y’all. The Civil War is about to end.

Take a moment and imagine what must have been going through Lee’s head in March of 1865. Waiting just a few hundred yards away was a Union army more than twice the size of his own–and now that winter was finally over, they were itching for a fight. Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had spent the first nine months of the siege trying to encircle Petersburg and cut off supply and escape routes from the city. But as Lee’s situation grew less favorable and Grant further strengthened and supplied his army, it wasn’t a question of if Grant was going to launch a full assault to break Lee’s weakened defensive lines, but when. An attack was coming, and it was bound to happen in March. Lee, knowing he was working with a very small window of time, only had a handful of options. None of them looked good.

First, he could choose to surrender to Grant, something he wasn’t ready to do yet. The second option was to abandon Petersburg (and thus Richmond) and meet up with forces in North Carolina to reinforce his weakened army. While it would mean saving his men, losing the Confederate capital would be a huge blow. The third choice was the riskiest and yet, the most natural for Lee. What if he could take the fight to Grant? Waiting for a Federal attack at Petersburg wasn’t giving him any advantage, but if he could break through the siege lines and throw Grant off-kilter, he had a shot at regaining the advantage and potentially gain access to Grant’s rich supply operation at City Point, Virginia.

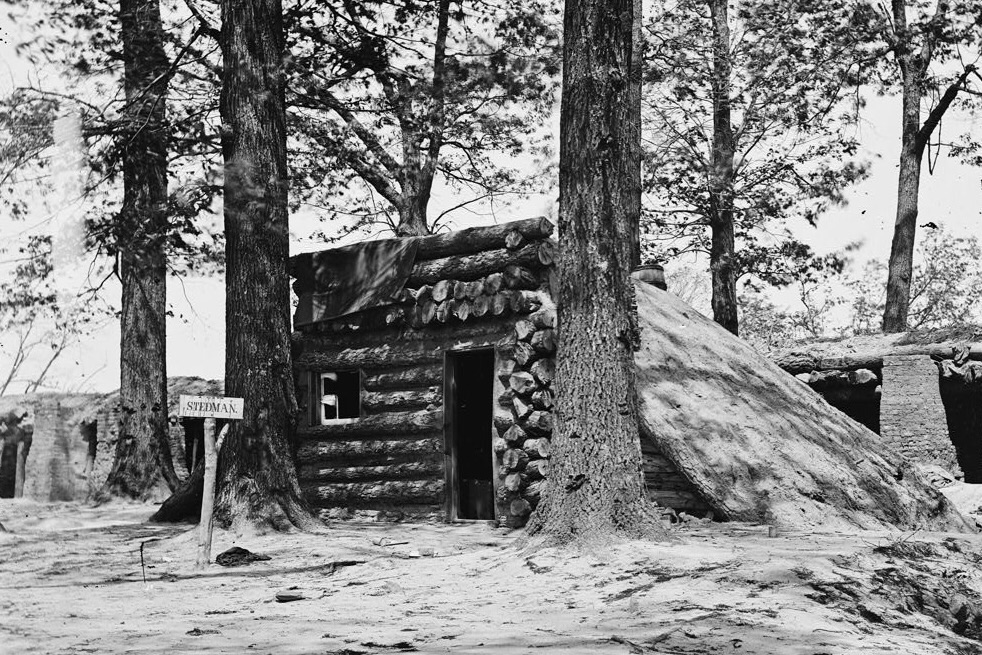

In early March, Lee tasked Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon to develop a plan for a surprise offensive against Grant. Gordon spent several weeks analyzing potential weaknesses in the Union siegeworks and returned with a plan on March 23rd. The plan centered on an assault on Fort Stedman, a strategically-located Union fortification that was close to Union supply lines. Confederate soldiers would take the fort, using it to base an attack along the Union line, creating a sizeable gap through which the main Confederate assault would take place. From there, the rebels would proceed all the way to the Union supply depot at City Point.

After reviewing Gordon’s plan, Lee put it into action almost immediately.

The attack began in the pre-dawn hours of March 25th. Under cover of darkness, Gordon sent sharpshooters across the “no man’s land” between the lines. In order to confuse the sentinels posted at the fort, the sharpshooters impersonated Confederate deserters, a common sight during the overnight hours.

The guards didn’t realize their mistake until the rebels were on top of them, and were quickly overtaken without shots fired–in fact, those first Confederates were ordered to attack with unloaded rifles because they couldn’t risk an accidental misfire alerting the other Union soldiers. Once the guards were neutralized, many more Confederates crossed into the fort. Since most Union soldiers inside were asleep or caught unaware, Fort Stedman was quickly taken.

In the scuffle, some artillery shots were fired by a nearby battery, but that was soon overrun by rebels as well. Gordon had taken the fort so quickly that they still had 45 minutes until sunrise. Thanks to some cut telegraph wires, the Union command were unaware of the attack until much later.

The Union general in charge of that section of the line (and Fort Stedman), Gen. Napoleon B. McLaughlen, was awoken by the noise of the attack, quickly dressed himself, and rode out to nearby Fort Haskell. He was informed that Confederates had overtaken a nearby battery, and he ordered an artillery attack on it. Unaware of the scale of the assault, McLaughlen headed directly to Fort Stedman to assess the situation there.

Upon arriving, he saw soldiers, who he assumed to be Union picketers returning to the fort, coming over the breastworks. McLaughlen shouted orders, which they quickly obeyed. He was soon dismayed to discover that the soldiers he’d been ordering around in the dark were actually Confederates. Just as quickly, the rebels realized his identity as well, and McLaughlen was quickly captured and forced to surrender the fort to Gordon.

Maj. Gen. Gordon knew time was of the essence–troops were sent left and right along the Union lines to capture whatever batteries and forts they could, while Confederate artillerists worked to turn captured Union artillery guns in the opposite direction. Meanwhile, Confederate infantry streamed into the gap that was opened by the surprise attack. Things could not have been going better for Gordon, who would later write that the attack had “exceeded my most sanguine expectations.”

As morning light broke, however, things started to turn in the other direction.

It wasn’t long before Gordon began receiving reports of heavy Union resistance from the Confederate troops he’d sent out to capture additional forts. Soon after, a punishing artillery fire from nearby forts started to rain down on Fort Stedman. In addition, word reached him that the reinforcements he had been counting on to strengthen the main assault had been delayed.

Now with the aid of sunlight, a more formal Union counterattack began to form. The Union confusion and panic that Gordon had counted on now evaporated with the night’s darkness. It became clear that the Confederates would not be able to hold the fort for much longer. Gordon ordered a full evacuation back across the no man’s land to Confederate lines. As they ran back across the open ground between the lines, they were subject to blistering musket fire from the Union soldiers, who could now pick them off easily in the daylight. A Union observer wrote:

My mind sickens at the memory of it–a real tragedy in war–for the victims had ceased fighting, and were now struggling between imprisonment and death or home.1

Four hours after it was taken, Fort Stedman was safely back in Union hands. The offensive had failed, and Lee, who had lost over 4,000 soldiers in the assault, knew his position at Petersburg was no longer tenable. In a week, Grant would launch a Union offensive that would break the Confederate lines and end the Petersburg siege, creating a rapid series of events that would lead to the fall of Richmond, the surrender of Lee, and the end of the Confederacy.

The long bloody war was finally coming to an end.

— ∮∮∮ —

April will be the final month of this Civil War series–much of the important stuff happened right here in Richmond! Check back often for the last few real-time installments of our four-year-long series!

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864 – April 1865. pg. 354 ↩

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.