Biograph Times: The Devils & the Details

Note: February 11 is a special date for me; here is why: My first good look at what was to become Richmond’s version of a repertory cinema, the Biograph Theatre, was in July of 1971. At that point it was a few cinderblocks in a hole in the ground. Having gotten a tip the DeeCee owners […]

Note: February 11 is a special date for me; here is why:

My first good look at what was to become Richmond’s version of a repertory cinema, the Biograph Theatre, was in July of 1971. At that point it was a few cinderblocks in a hole in the ground. Having gotten a tip the DeeCee owners were considering hiring a local manager, I went to the construction site chasing the opportunity.

A couple of months later I was offered what seemed then to be the best job in the Fan District. The adventure that followed went far beyond any expectations I might have had, at age 23, about becoming the manager of the Biograph Theatre.

On the evening of February 11, 1972, the new venture at 814 West Grace Street was launched with a gem of a party. The local press was all over it. The first feature presented was a delightful French war-mocking comedy — “King of Hearts” (1966). On Richmond’s newest silver screen, Genevieve Bujold was dazzling opposite the droll Alan Bates. In the lobby, as flashbulbs popped the dry champagne flowed steadily.

During the ‘60s, college film societies thrived. Knowing film was cool; it could get you laid. By the ‘70s, many of the kids who had grown up on television worshiped classic movies, some had become connoisseurs of the moving image. Popular culture, in general, was becoming a subject for serious study on campus for the first time.

So it was the fashion of the day elevated many foreign movies, certain American classics, and selected underground films above their more accessible, current-release, Hollywood counterparts. In that pre-cable TV age, much of the mainstream domestic product was viewed by the film buff in-crowd as laughingly naive or hopelessly corrupt.

Although none of them had any prior experience in Show Biz a group of five men, then in their mid-30s, opened Georgetown’s Biograph Theatre (1967-96) in 1967. They were trendy, smart guys and at least one of them knew a lot about foreign films and film history. They caught a wave. A few years later those same young owners were successful, confident and looking to expand. In Richmond’s Fan District they thought they had found a perfect situation for a second repertory-style cinema, another Biograph.

Local players, filthy rich Morgan Massey and deal-maker Graham “Squirrel” Pembrooke, built the Biograph building from scratch for the Georgetown group. Significantly, Pembroke managed to get a 20-year lease for $3,000-a-month rent guaranteed by a federal program for at-risk neighborhoods, in case the edgy concept didn’t fly and the operators went belly up. Thus, when the Biograph closed in 1987 the building’s owners were then able to collect the rent from Uncle Sam until 1992.

Knowing they could walk away easily, if the business fizzled, the Biograph’s creators — chiefly David Levy (who later owned The Key on Wisconsin in Georgetown) and Alan Rubin — inked the deal and borrowed money to buy a load of very used seats and projection booth equipment, which included ancient Peerless carbon arc lamps to back up a pair of rugged Simplex 35 mm projectors.

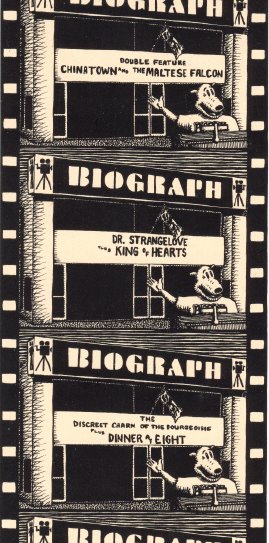

Biograph programs, printed schedules with film notes, covered about six weeks each. Double features were the staple. Program No. 1 was heavy on documentaries, featuring the work of de Antonio and Pennebaker, among others. Also on that program were several films by revered European directors, including Antonioni, Costa-Gavras, Fellini, and Polanski.

After the opening flurry, with long lines to every show, it was somewhat surprising and disappointing when the crowds shrank dramatically in the third and fourth months of operation. As VCU students were a substantial portion of theater’s initial crowd, the slump was chalked off to exams and summer vacation.

In that context, the first summer of operation was opened to experimentation aimed at drawing customers from beyond the borders of the immediate neighborhood. The brightest light in the mix of celluloid offerings was just such an experiment that caught on — Friday and Saturday midnight shows. (more…)

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

This article has been closed to further comments.