Stealing home: Fulton as its residents knew it

Yesterday’s Fulton was reduced to rubble, but it’s not forgotten.

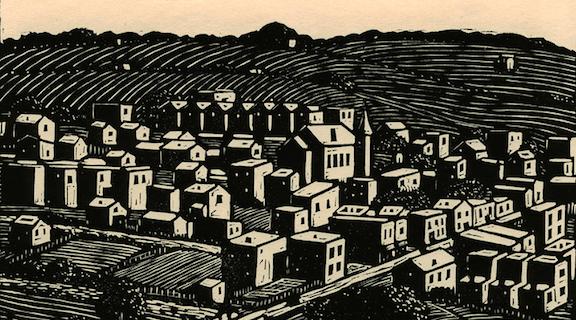

From a Charles W. Smith print, courtesy of the Valentine. View the original here.

The outfielders that summer afternoon were playing deep, and justifiably so. A ball hit between them might just roll all the way to the foot of Chimborazo Hill, and by the time one of them grabbed it and whirled to throw, why, the batter would’ve already turned his back to Richmond as he rounded third base and began sprinting home, toward the town of Fulton.

And as he ran that way he could’ve seen so much. To his left were the spires of the town’s two churches, aligned perfectly with home plate, like stars in a constellation. Straight ahead was the lazy slope of Powhatan Hill, where not three centuries earlier John Smith and Christopher Newport met with Chief Powhatan’s son and set into motion a chain effect of cruelty that would, some 80 years after this photograph was taken, tear down damn near every building in Fulton.

But if he’d looked to the right, just over the shoulders of his cheering teammates, he would have seen a bridge about 50 feet from the plate he was racing toward. It was about as humble as bridges get, spanning a trickling tributary of the James called Gillies Creek, 15 yards long and barely wide enough for two horse-drawn buggies to pass at the same time. The twin brick supports beneath that bridge, their gaptoothed yawns almost hidden by undergrowth today, remain Fulton’s oldest structures to survive the days when the bulldozers arrived and one of Richmond’s most obscene larcenies began.

Rosa Coleman remembers learning to smoke, under the careful tutelage of an older middle schooler, under the bridge in the late 1960s. By then the baseball field was long gone, but a new church–one of three that had been built in Fulton in the 20th century–cast a tented shadow over the bridge just beneath it.

Despite the new construction, however, much of Fulton had fallen into disrepair by the time Coleman first ventured beneath the bridge. Many of its rowhouses–which would have been built around the same time as those in nearby Church Hill, and looked similar–had begun to fall apart. Residents, nearly all of whom were low- to middle-class blacks, often lacked the resources necessary to repair them. Still, Coleman recalls with a smile, “there’s no place else in the world where I’d have rather grown up.”

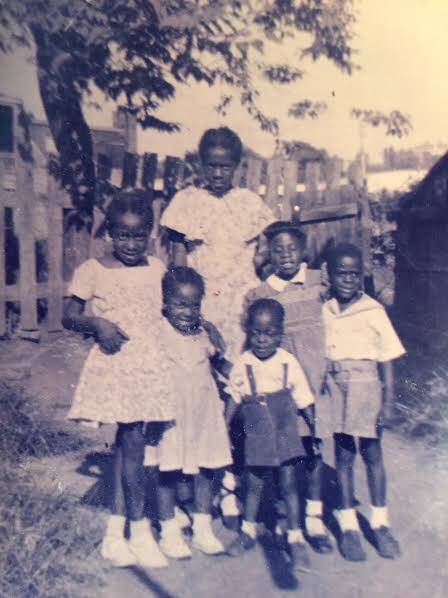

An undated photo of children in Fulton. Credit: Rosa Coleman. Used with permission.

The sentiment makes sense when you consider just how a town–technically a neighborhood, Fulton having been annexed by Richmond in 1905–so small could have supported so many churches. Fulton’s greatest offering to its residents wasn’t so much an outlet for their religious inclinations but instead something even deeper, something represented by those churches: Sanctuary. And was it ever needed.

A horrifying photo, published in the March 1960 edition of Life magazine, shows a 58-year-old black woman carried away from Thalhimers department store by two police officers, barking German Shepherd in tow. Ruth Nelson Tinsley would be arrested and later convicted on the charge of “refusing to move when told to do so by a police officer.” It was a reminder that 100 years earlier the Civil War hadn’t even begun, and that the intervening years had done little to change the prevailing attitudes of racism in the Confederate capital.

And yet–as sit-ins were staged at diners on Broad Street, and a young minister from Georgia began to emerge as a leader in what would be called the Civil Rights Movement–Coleman can’t remember ever once feeling victimized by discrimination. “We didn’t feel any of that in Fulton,” she says, pausing for emphasis. “It just didn’t exist where we lived.”

Part of this is due to simple geography. Hemmed in by Chimborazo Hill to the north, the James River to the west and Powhatan Hill to the east, Fulton was always destined to be somewhat insulated from the tumult and anger so evident in downtown Richmond.

Most of that feeling of sanctuary, however, was nurtured by Fulton’s self-sufficiency as a community. While thousands of Richmond’s blacks were uneasily adjusting to life in the newly built housing projects–cheerless and uninviting slums on the city’s periphery, where they remain conspicuously removed from meaningful municipal amenities–those in Fulton enjoyed all the resources and features of a fully realized community.

They had their own bank and their own gas station. If they needed groceries, they could shop at Grubb’s or the A&P. There were three barber shops, two movie theaters, and a hardware store. They could go to Allen’s Shoe Shine Parlor while they waited for their clothes to be ready for pickup at the Nu-Way Cleaners. Students went to Webster Davis Elementary and when it snowed would slide down Powhatan Hill on cardboard boxes found behind Evan’s Supermarket or J.A. Black & Sons’ furniture store, or on car hoods hastily snatched from Fogg’s junk yard. For less wholesome diversions, there was even a pool hall and what one former resident described as “plenty of nip joints.”

And then, of course, there were the residents themselves. The nobly conceived and exquisitely researched Historic Fulton Oral History Project is filled with disparate memories from former residents that coalesce like a Pointillist painting into a portrait of an unbelievably proud and tight-knit community. There were neither strangers nor secrets in Fulton, and so it wasn’t unusual for parents to host uninvited kids for dinner – or discipline others upon catching them misbehaving. Coleman remembers a handful of times when she’d return home with a bruised bottom from a friend’s house only to discover that word of her misdeeds had already beaten her there. “Second whoopings,” she remembers, “were a part of growing up in Fulton.”

Now president of the Greater Fulton Civic Association, Coleman speaks even more ruefully of the day her parents accepted the city’s relocation package in the early 1970s; Fulton’s homeowners were offered $15,000 and a new home elsewhere. “We were heartbroken, because it broke us up as a family,” she says, speaking of her neighbors who similarly scattered across the city. It’s a choice her family should never have been forced to make.

Much of Fulton’s gradual descent into its condition in the 1960s is attributable to its oversight and neglect by city officials. In citing rampant structural dilapidation after decades of failure to enforce building codes as the primary motive for Fulton’s dissolution, Richmond authorities acted no better than callous slumlords, and the resultant neighborhood they built once the bulldozers finally left is nearly as disgraceful.

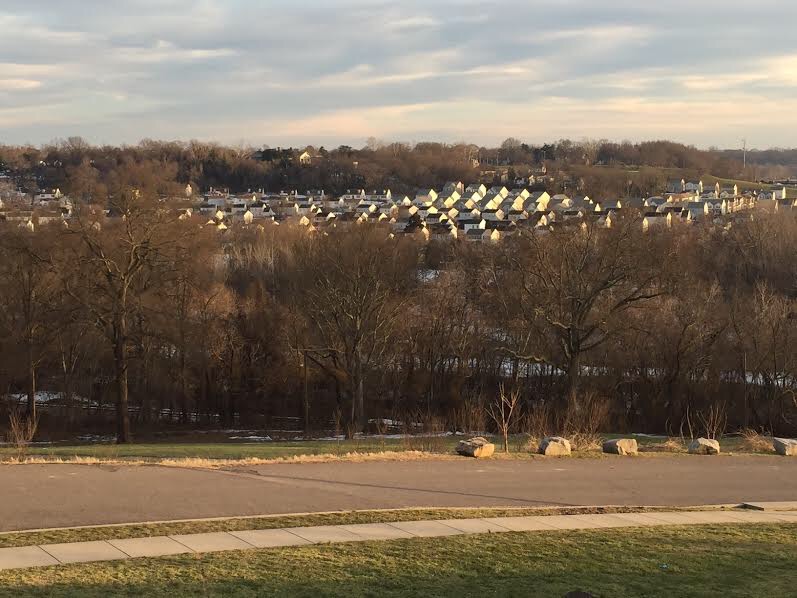

Fulton from Chimborazo Hill in 2016.

Gone are the rowhouses, replaced by cheaply produced and tightly bunched homes of such eerily uniform design as to call to mind something from a Ray Bradbury story. Gone is the grid system, replaced by an utterly illogical abundance of cul-de-sacs, effectively discouraging the easy interaction the neighborhood’s residents once so freely enjoyed. And gone, most sadly, is every tangible landmark that might help newer generations understand how Fulton used to look, back when the neighborhood was a rare beacon of pride during a tragically dark time for Richmond’s black community.

Every landmark, that is, but one, connecting not just banks of a creek but eras in Richmond history.

Looking at the full version of this photo of Fulton taken sometime in the 1890s, every old landmark falls into place once you’re able to locate the bridge. The largest church–the one with the beautiful open bell tower–was directly on what’s now a field used by River City Sports football and kickball leagues. The newer church, built next to the bridge, is where the horseshoe pits are today. That ramshackle white house, with four huge windows facing the baseball field, is exactly where the basket on the sixth hole of the Gillies Creek disc golf course stands today.

And the old baseball field itself? The city built Stony Run Road through its left field, and some scrubby trees have taken root behind second base and in shallow right field, but its basic infield dimensions are retained today by a weedy sand pit. It apparently used to be a pair of volleyball courts–there are two pairs of rotting 12-foot wooden beams near its middle, but the nets connecting them have long vanished–and whether the workers who constructed it were at all aware of what that expanse used to be remains impossible to ascertain.

What’s certain, however, is that the loss of this baseball field is nothing compared to the loss of a neighborhood so rich in character, so cherished by its residents. It’s easy to feel anger over its razing, or over what’s replaced it–but it’s perhaps better to feel gratitude that such a place existed at all. And still better is the thought of being in attendance that summer afternoon, perhaps with your feet dangling off a nearby bridge, watching a baseball player rounding third and running toward Fulton, running toward home.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 7 reader comments. Read them.