Byrd Park’s temperance fountain: A wet monument to a dry cause

Prohibition wasn’t long for this world when the temperance fountain was erected in 1927 in Byrd Park, but its tribute has stood the test of time.

As those first few soft spring raindrops fell from the swollen clouds above Byrd Park, Sarah Hoge must have felt something deeper, more unsettling, than simple disappointment. In front of her were a few hundred people, mostly ladies in formal attire, there to celebrate the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union’s newest contribution to the “dry” movement. All were swiftly becoming drenched.

Behind her stood the newly unveiled focal point of their gathering. It offered the very substance that was at that moment sending her audience scrambling for the nearest shelter. Its script contained an erroneous date and an outrageous boast. Most strikingly, it looked like an oversized tombstone – which in a way it was. As her supporters continued to flee in droves, Hoge must have contemplated the mocking rain falling on Richmond’s newest water fountain and thought, if only for an instant, “Perhaps Prohibition won’t last forever after all.”

An undated photo of Sarah Hoge with husband Howard

May 14, 1927 was supposed to have been among the proudest days in Hoge’s remarkable tenure as president of the WCTU’s Virginia chapter. The Loudoun County native had held her position since 1898, and had seen her chapter’s membership grow from fewer than 1,000 to nearly 11,000 in 1920, thanks largely to her perseverance and passion.

“Every department, every approach to Prohibition, the various ways of keeping it, are familiar to her,” a colleague would recall. “As a Christian, a philanthropist, and as one devoted to her home life, Mrs. Hoge ranks with Virginia’s best.”

Her galvanizing efforts, which included organizing letter-writing campaigns and delivering impassioned speeches throughout the state, were instrumental in the Virginia legislature’s decision to go dry in November 1916, three years before Prohibition was adopted nationwide. As 1927 began, she could count herself among the most accomplished women in the state – but there was still one thing she hadn’t done.

A temperance fountain in Coudersport, PA

At the WCTU’s inaugural convention in 1874, national president Annie Turner Wittenmyer urged the delegates in attendance to return to their home towns and erect water fountains. Their purpose – which she ostensibly explained with a straight face – would be to discourage men from entering saloons to quench their thirst with booze. The apparent shortsightedness here is amplified by the fact that most running water at that time was of such dubious quality that alcoholic drinks were generally considered a healthier alternative.

But no matter. WCTU members tackled this new imperative with characteristic zeal, and before long most states could boast at least one fountain; Massachusetts alone had nine. For Hoge, that her home state hadn’t yet built one more than 50 years after being instructed to must have been a gnawing vexation.

Her members soon raised the funds for the Virginia fountain’s construction and elected to unveil it in the busiest park of its capital city on “Play Day,” an annual event for which Byrd Park would have been packed with citizens watching and participating in various amusements such as a fiddlers’ contest and a marbles competition.

Postcard of Byrd Park, ca. 1920s

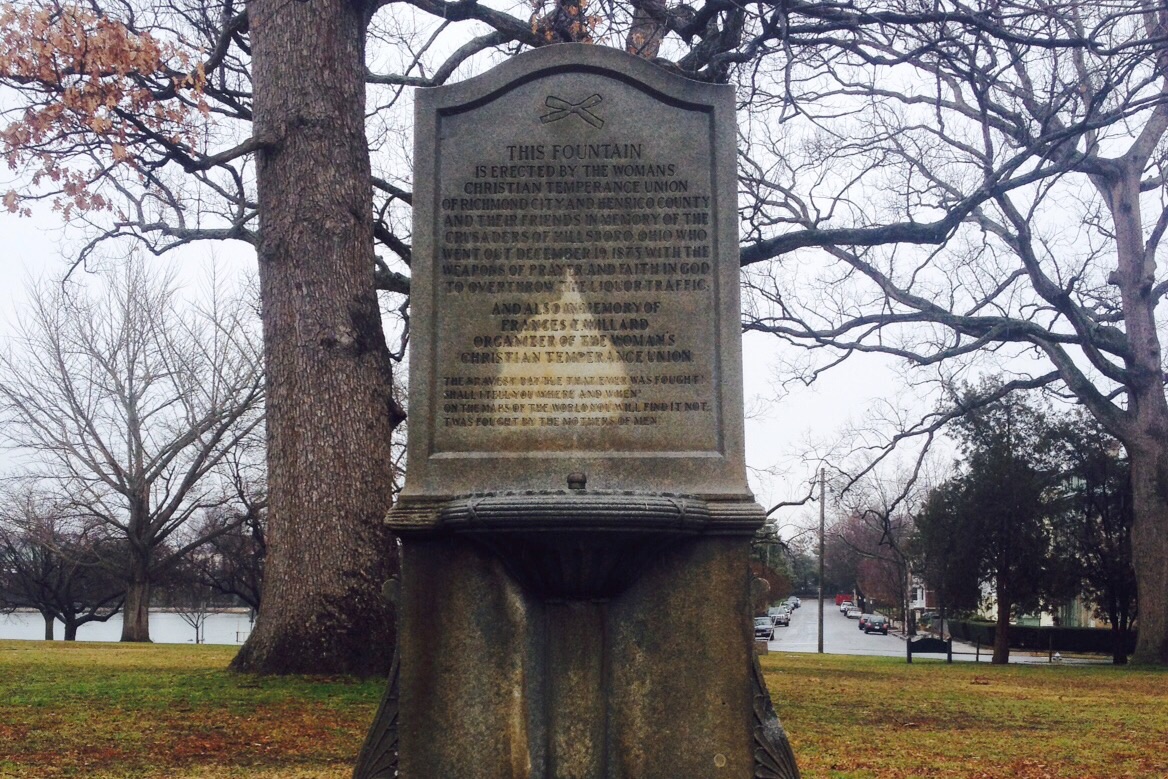

Those in attendance for the unveiling would have likely, upon leaning forward and squinting to read the curiously small script on the fountain, been bemused by what they saw. Beneath the WCTU’s symbolic white ribbon, the marker reads:

THIS FOUNTAIN IS ERECTED BY THE WOMANS CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION OF RICHMOND CITY AND HENRICO COUNTY AND THEIR FRIENDS IN MEMORY OF THE CRUSADERS OF HILLSBORO, OHIO WHO WENT OUT DECEMBER 19, 1873 WITH THE WEAPONS OF PRAYER AND FAITH IN GOD TO OVERTHROW THE LIQUOR TRAFFIC:

AND ALSO IN MEMORY OF FRANCES E. WILLARD ORGANIZER OF THE WOMAN’S CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION

THE BRAVEST BATTLE THAT EVER WAS FOUGHT? SHALL I TELL YOU WHERE AND WHEN? ON THE MAPS OF THE WORLD YOU’LL FIND IT NOT, ‘TWAS FOUGHT BY THE MOTHERS OF MEN!

The omission of the apostrophe in “Woman’s” isn’t even the most inexplicable typo of the first section. By all historical accounts, the Hillsboro protest occurred on December 23. On that night, some 70 women–inspired by a speech they’d just heard from temperance activist and certifiable nut job Diocletian Lewis–prayed inside each of Hillboro’s saloons until their respective owners decided to close business for the night, presumably filling the frosty air with four-letter words as they locked their doors.

A print depicting the night of December 23, 1873

This event marked the unofficial beginning of the temperance movement, and its date would almost certainly have been committed to memory by a leader as devoted to her cause as Hoge. Whether she was unable to proofread the text before it was etched or had simply misplaced her trust in one of her subordinates to get the job done correctly remains unknown. What’s certain, however, is that her reaction as the veil was lifted would have been the most GIF-able moment of 1927’s Play Day.

Then there’s the matter of the poem at the bottom of the marker. It reads as hyperbole today, and could well have seemed downright tasteless by many in 1927. For the WCTU to deem its crusade “the bravest battle that was ever fought” on a statue in Richmond, former capital of a Confederacy for which hundreds of thousands had lost their lives, seems particularly galling. The poem wasn’t original–it had been penned decades earlier by a man named Joaquin Miller, and it wasn’t even about the temperance movement–and should probably have been left off the fountain altogether.

The truth is, Hoge had to have sensed the impending end of Prohibition even before the rain forced the ceremony’s abrupt cancellation that day. By 1927, drinking both in Virginia and nationwide appears to have been at or even in excess of its popularity a decade earlier, and its prohibition had allowed organized crime and illegal bootlegging operations to thrive. Support for the temperance movement had peaked years earlier; membership in the Virginia chapter of the WCTU had been steadily decreasing since 1920. Hoge would remain president of that chapter until 1938 – five years after the 21st Amendment ended the Prohibition era she’d worked so hard to bring about – waging her unwinnable war for as long as she could. She died the following year at 82.

There’s no more fitting home for Hoge’s fountain than here in Richmond, surrounded by so many other monuments to those who fought bravely in their own unwinnable wars. According to the city’s Parks Department, its water supply was shut off more than four decades ago when its underground piping began to deteriorate. That no one in the department could pinpoint the exact year in which the water was cut off speaks to how little attention that decision must have generated at the time, and how few in Byrd Park must have noticed the change.

But the fountain remains, reminding us of a forgotten fight and its failure, and looking especially beautiful when it rains.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 3 reader comments. Read them.