De-Venerating Richmond’s Confederate symbols

Here’s a list of all the ways the City still honors individuals who symbolize hate to many, many people. What does it all mean, and how can we move forward from here?

By Susan Howson & Ross Catrow

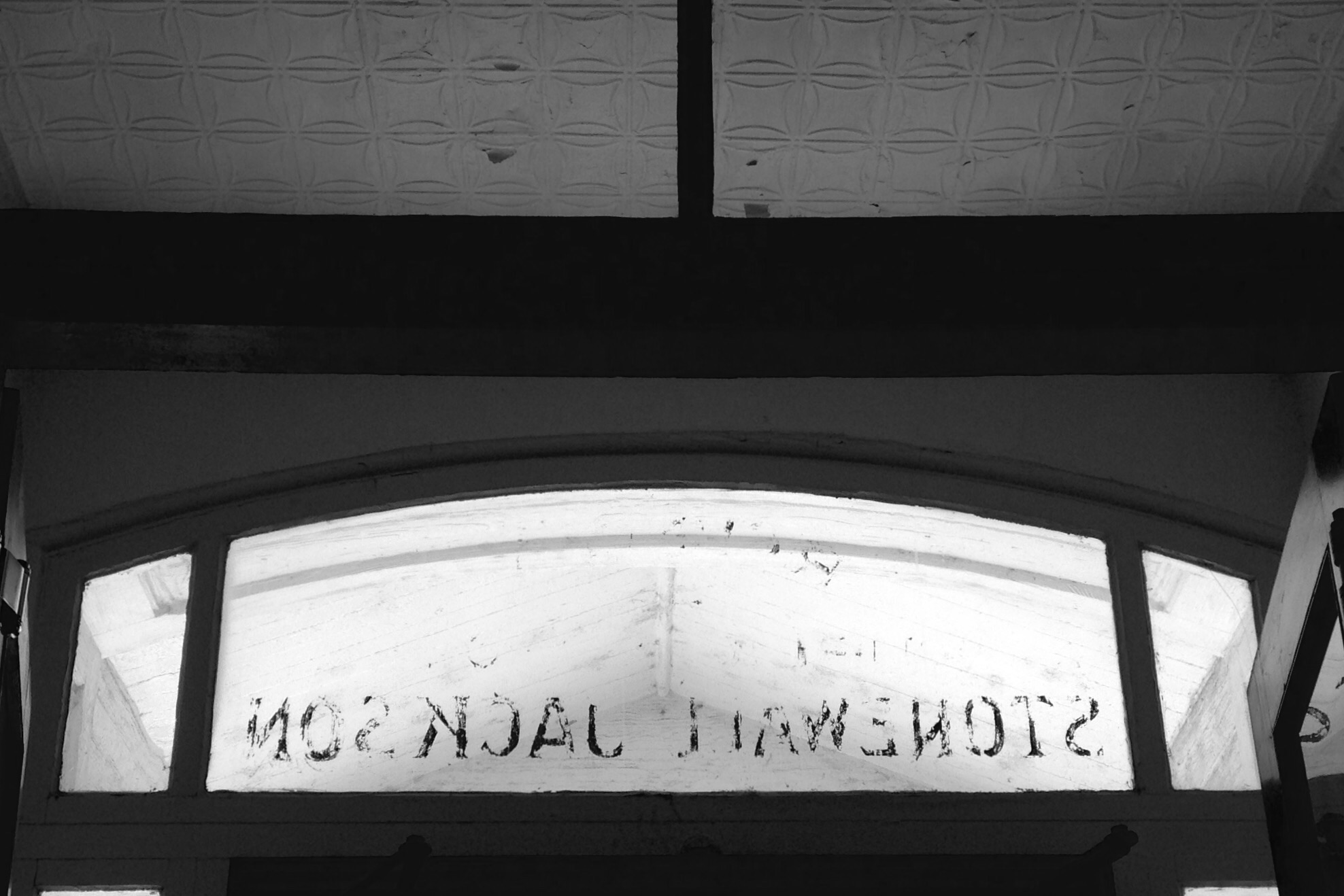

Every day, the RVANews staff climbs the steps to our office within the Stonewall Jackson Professional Building, which lies a few blocks from Stuart Circle, which lies a few blocks from…well, the list goes on and on. You could spend hours using a Richmond map to play connect-the-dots with places, streets, and, of course, statues that not just memorialize but honor a few individuals that literally and figuratively led the charge in favor of enslaving human beings.

Yet several months ago, we (along with so many others) decried the existence of an anti-gay billboard. We opposed the erection of a giant Confederate battle flag over I-95, and we are always, always quick to point out sexism wherever and whenever we can.

But here we are, in the Stonewall Jackson Professional Building, thinking we’re pretty progressive.

Have we just become used to the sight of these streets on a map, these schools in our neighborhoods, and these statues we drive around? Do we really want them mixed in with the pride we take in our city? Or are they valuable because they start conversations about our oft-problematic history, as many have argued?

For these aren’t just meaningless names of schools or streets. Nobody shrugged their shoulders and said “Semmes, that sounds like a cool name.” No, they said “We should honor Raphael Semmes, Confederate naval superstar, by naming this street after him.” These were conscious decisions, often made in other times of troubling racial tension, to make statements. They reached back into the past and brought forward a guy who stood for something instead of lots of other guys and gals who stood for lots of other things. Semmes Avenue is intentional. Stonewall Jackson’s monument is intentional. J.E.B. Stuart Elementary School is intentional.

If in 2015, we wouldn’t erect a monument, name a street, or christen a building in honor of a man whose name is synonymous with hate and racial violence, why do we allow those names to remain honored in 2015? Perhaps it’s because we associate them with the other things we love about the South–peach pies, sweet tea, chirping crickets, our river, our pace, our way of life. And those things are amazing. But they will still exist no matter what Jefferson Davis Highway is called.

As media, we face another dilemma. In our industry, it’s good timing right now to cover this issue. Charleston is on everyone’s minds, and our job is to give national news a platform on which we relate it to Richmond, and we want to talk about what Richmonders want to read about. But it’s also bad timing because we run the risk of contributing to the problem that’s incensing people we respect, like Marc Cheatham–we can’t just take down Confederate flags and pat ourselves on the back for having dealt with the race question once and for all.

But does that mean we should appear–and emphasis on “appear” here–to celebrate these symbols? Is that the face we want to show the world? Or, maybe more importantly, is it how we want our fellow Richmond citizens to think about each other?

We’re positive it’s not. So what can we do to make sure we don’t project that image? Add more good, new things to try to outnumber the old? Move the offensive stuff to a museum? Get rid of it entirely? Sit in our living room with a blanket over our head and try to pretend like none of it’s happening? We personally just don’t know.

We’re working on some practical steps on our end. For instance, we’ll no longer select Picture of the Day or Instagram of the Day submissions that include anything that honors a Confederate figure. That’s just glorifying a glorification, which we’re not into.

Maybe as a community, we could consider petitioning the School Board to change J.E.B. Stuart Elementary School’s name or asking the City Council to change some street names (it could happen without altering any laws, see below). Perhaps we could petition our landlords to change the names of our buildings–we’ll start with ours. You never know, maybe he’ll be into it.

What will you do to help make sure this isn’t how the world sees us, and it isn’t how we see ourselves?

Below you’ll find an inventory of sorts of our city’s physical Confederate baggage. It’s not a complete list, but it’s instructive to see what exists and where. Below that you’ll find some quotes from people who are black, white, male, female, of different ages, origins, and professions. All that matters is that they’re Richmonders, and these are their thoughts on the matter.

Our Confederate inventory

J.E.B. Stuart Elementary School

Established in 1921, J.E.B. Elementary School on the North Side seems like low-hanging fruit on the name-changing tree.

Roads

Of Confederate-named roadways, we’ve got about eight that make up 16.1 miles of City’s 1,320 miles–that’s 1.2% of mileage With commonplace names like Stuart, Lee, and Davis, it’s hard to know which roads are named for which guy. For example: Mosby Street may not be named after John S. Mosby and Stuart Avenue might be named for J.E.B. Stuart.

- Jefferson Davis Highway

- Maury Street

- Semmes Avenue

- Mosby Street

- Stonewall Avenue

- Davis Avenue

- Confederate Avenue

- Stuart Circle

Beautiful map and data by Taber Andrew Bain.

If we wanted to get some of the names of streets and schools and buildings changed, the city code outlines the requirements. Note that “discriminatory or derogatory names from the point of view of race, sex, color, creed, political affiliation or other social factors, shall be avoided.”

Monuments

Most of this list was pulled from the super useful and super interesting Richmond on the James Blog where Phil Riggan has done yeoman’s work cataloging our city’s statues–Confederate or otherwise.

- Stonewall Jackson — Capitol Square (1875)

- Robert E. Lee — Monument & Allen (1890)

- William Carter Wickham — Monroe Park (1891)

- A.P. Hill — Laburnum & Hermitage (1892)

- Richmond Howitzers (1892)

- William “Extra Billy” Smith — Capitol Square (1906)

- J.E.B. Stuart — Monument & Lombardy (1907)

- Jefferson Davis — Monument & Davis (1907)

- Stonewall Jackson — Monument & Boulevard (1919)

- Matthew Fontaine Maury — Monument & Belmont (1929)

- Fitzhugh Lee — Monroe Park (1955)

What Some Richmonders Think

These views belong to each individual, personally, and do not necessarily represent those of their organization.

Evandra Catherine, VCU Department of African-American Studies

At the end of the day, we have to understand our history so we can grow from it and heal. The history of blacks was told from a different perspective, but what we get is a situation where we’re only getting one side of the story, and that story is very painful, and that’s really because the extra piece of history isn’t there…

Getting rid of these monuments and symbols is problematic because if it’s not there and you don’t see it, it might not spark conversation. It needs to be a healing that happens together. Blacks healing together, whites healing together. How can we heal together if we don’t come around these symbols and things and talk about them? How did this person’s presence impact all people? …

Let’s have a dialogue, let’s talk about these things, come on. Let’s talk about it together and understand each other. Let me not think that because you have a Confederate flag on your shirt that you think I’m inferior to you, but maybe that you wear it because you have a great-grandfather who lost his life in the war…

I don’t want to get to a point in this country where we take all these symbols down and stop having conversations about them.

Ana Edwards, Defenders of Freedom, Justice, and Equality

I was born and raised in LA, but in my ancestry, my people did come out of Virginia. In fact, we were part of the enslaved population that was sold out of Virginia. Living a contemporary life as an African-American person–I’ve been here 27 years–my first impressions coming here were that I felt like I was stepping into a movie that was based in the Civil War era. Driving around the city of Richmond, it’s been reinforced over and over again by people who have moved here form other places, in conversation with other black people. Richmond is a Confederate memorial…

Richmond’s history is vast, it’s rich, it’s deep, it’s complicated, and we are so much more than that. The heart of the conflict of the entire American story can been told here…

To me, there’s elements of both sadness and hope. We would like Richmond to reflect much more of this history, [right now,] it’s a very very narrow perspective. The fact that it’s literally the central landscape of the UCI race–this is what they’re showing off!…

What’s happened in Charleston most recently is not the only example, but it has provided the catalyst be willing to be vocal.

We should be considering moving these symbols into archival and museum places.

It’s very easy to use the thing that creates the most response in the public. In a way, I totally understand and am sympathetic, you have all these public officials who are finally ready to pull down the flag and stop selling memorabilia, and they’re not going to take the same energy to look at how we address racism in our communities. That legacy has been the economic and social disenfranchisement of black people in this country. Those concrete institutionalized problems have to be addressed.

It’s not that I’m advocating for the utter removal of all traces of this history–in a way, we’re talking about a balance. In Richmond, the dominant landscape is that landscape. We believe that there’s that emphasis, and we believe in thinking of Richmond’s identity as much larger than that…

Richmond is overdue, we need to do it. We’re doing it now. We have a unique opportunity, if, during an event like the Worlds race, that we can show Richmond that not only are we acknowledging that this needs to be relegated to history. We should expand how we show our history to include the origins of the development of the US or our relationship to Indian history. If we can show that to the world during the UCI bike race, then we can show the world that we are a smart, compassionate, progressive city.

Anedra Bourne, Tourism Coordinator for the City of Richmond

I do think that Richmond is known for history of various periods, not solely of Civil War history, but obviously with the sesquicentennial coming to an end, that conversation has been elevated in a very real, comprehensive way to be more inclusive of a true American history that related to the northern perspective, the African-American history.

I think people have been able to embrace the other sides of history that they had not had before–the good, the bad, the ugly.

I think people take [the symbolism and imagery] for what it is and are eager to learn more about portions of any kind of history…

Would that change the conversation [if certain moveable symbols were moved to a museum]? The history behind them still exists. Would that really change the conversation? I don’t know.

But I think Richmond is an evolving city. History’s almost more the backdrop now to the up-and-coming pieces of what we have to offer the destination. Until items of national significance come about to rehash or reevaluate the history, I don’t think it’s as much a part of our daily dialogue [as it used to be].

Bill Martin, Director, The Valentine Museum

Places like the Valentine and VHS and American History museum and National Parks are where those conversations should happen, and Richmond has these great institutions to help in that conversation. We’ve got great collections that would support the conversations and the research that inform our opinions. All of us have an important responsibility and role in how we portray conversations about our history.

Tag Christof, Art Director – Editorial — Need Supply

I’m from an old Spanish family in New Mexico, a place with its own deep scars from regional conflict and a strange relationship with American culture at large–through battles and annexations, we not only lost our “country,” we lost our language and most of our identity in the process. So, in some way, I empathize with the deep sense of cultural loss that permeates discourse about the South among some Southerners.

However, I believe that veneration of the Confederacy in 2015 is unequivocally wrong. It is impossible to separate even the most romantic ideas about it from an endorsement of slavery and racism, and with rising racial tensions across the country there is very little room to interpret honoring staunch “Confederate guys” as anything other than grossly insensitive. Even Robert E. Lee became a pragmatist after the war.

Instead of clinging to a cause that once united the South for antiquated reasons, many of which are appalling in retrospect, one would hope that it is time for new symbols and new common causes that celebrate and unite its deep, rich culture in much more inclusive ways.

Tiffany Jana, Founder & CEO — TMI Consulting

I grew up in Germany, and we had to learn about the Holocaust every single year. We visited concentration camps annually and even as small children, we were not shielded from the horrific reality of genocide. When I returned to the US school system, slavery was about one paragraph in a history class–and it didn’t sound all that bad. We have yet to have an open, honest national dialogue about the reality of our painful history and the implications on contemporary society.

Confederate symbols serve as a reminder that the racial disparities that plague every health, wealth, and progress indicator of a civilized society–are all out of balance by design. We live in the United States of its founders’ creation. I am all for honoring history and heritage, but not at the expense of the already marginalized. I suggest relocating all of the confederate trophies and symbols from Monument Avenue and elsewhere to a contained district where they can be memorialized and visited by people who wish to honor their heritage, and out of sight from the general population. I do not believe that Richmond, or any other US city, benefits from glorifying any part of our history that we cannot be universally proud of. These symbols divide us at a time when we need unity more than ever.

What some non-Richmonders think

Barack Obama, President of the United States

Progress is real, we have to take hope from that progress, but what is also real is that the march isn’t over, and the work is not yet completed. And then our job is, in very concrete ways, to try and figure out what more can we do?

Jeb Bush, 2016 Presidential Candidate, via his Facebook page

My position on how to address the Confederate flag is clear. In Florida, we acted, moving the flag from the state grounds to a museum where it belonged.

Michael Jackson, King of Pop

I’m starting with the man in the mirror. I’m asking him to change his ways. And no message could have been any clearer. If you want to make the world a better place. Take a look at yourself and then make that change!

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 33 reader comments. Read them.