Civil War: The winter drags on

For the Confederate soldiers and citizens of Petersburg behind siege lines, things grow more difficult and food becomes scarce.

As 1864 drew to a close, the Union and Confederate armies at Petersburg were both in their winter camps awaiting the inevitable arrival of spring and a return to major fighting. On the Union side, a vast supply operation based in City Point kept soldiers fed, clothed, and equipped for the winter months. For the Confederate soldiers and citizens of Petersburg on the other side of the siege lines, things had grown more difficult. For the past several months, Union General Ulysses S. Grant had attempted to cut off Petersburg from its few remaining supply lines. Despite their best efforts, a few still remained open, but the squeeze play had its desired effect of limiting travel (and thus, supplies) in and out of the city. Beyond Petersburg, Union General William T. Sherman waged a campaign of devastation across the fertile farmland of the South, causing food shortages that rippled throughout the entire Confederacy–but particularly in the besieged city and its neighbor, Richmond.

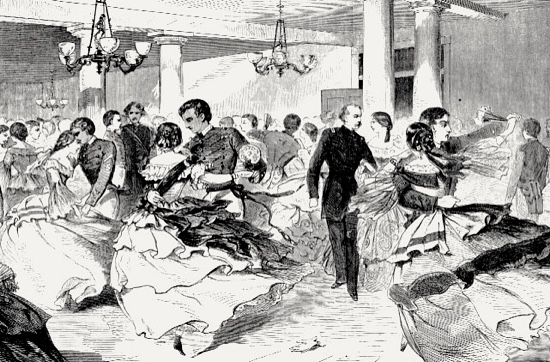

In the city itself, citizens were subject to massive price hikes on food and shortages on heating supplies. The problem was exacerbated by a steady stream of returning refugees into the city, who had evacuated the city during hostilities, but came back during the quieter winter months. Not ones to let a food shortage stop a good time, socialites in Petersburg and Richmond hosted “starvation parties” to distract from their woes. These parties were similar to the grand galas and dances held before the war, but without the benefit of food being served. Soldiers also intermingled in the social scene of Petersburg, attending starvation parties and finding other opportunities to distract them from life in camp. The winter of 1864 saw a number of somewhat hasty marriages between soldiers and the ladies of Petersburg. R.P. Scarborough wrote:

A great many of the soldiers are marrying around and in Petersburg, some for life, some for the war and some for one winter only.” Trudeau, Noah Andre • _The Last Citadel_

It’s hard to get an exact read on how Confederate soldiers fared during the winter of 1864. It was clear that the lack of supplies and food had an impact, but the effects seemed to vary depending on what unit you belonged to, and perhaps, the resourcefulness of your company’s quartermaster. In letters home, some soldiers reported having plenty to eat–including some who supplemented their rations with packages sent from home or food purchased in Petersburg. Other units reported a significant lack of food and suffering during the winter, telling stories of severely reduced rations and going several days without meat. The most common experience, it seems, was somewhere in the middle:

Before Christmas the official daily ration in the Army of Northern Virginia consisted of one point of beef or one-third pound of bacon, one pound of flour or meal, sixteen ounces of rice, and small quantities of vinegar, salt, and soap. Those troops on front line duty in the trenches received a bonus allotment of coffee and sugar. “‘Tis true,” observed an officer in the 27th North Carolina, “the rations we get are sometimes not such as a man with a good appetite could wish for, still we make out with them, and never really suffer for food.” Greene, A. Wilson • The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign

As the holidays approached, reports of the general lack of food and supplies for the soldiers on the front lines reached the public in Richmond, and a handful of citizens resolved to do something about it. They planned a grand gesture to show their gratitude for the soldiers and to help in whatever way they could. We’ll be telling the story of that gesture, and its impact on the soldiers, in just a few weeks.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.