Jackson Ward’s Lost Emperor: Charles Sidney Gilpin

Charles Sidney Gilpin was once a Broadway star and a stalwart detractor of African American stereotypes. What a bummer about his namesake, Gilpin Court.

Grant Martin, who’s been doing a lot of traveling this summer, has been sorely missed around these parts. In his absence, here’s a piece he did in October 2014 on his own website, OverlookedRVA.com about Charles Sidney Gilpin. Since Grant published this, there have been a number of really tragic events in Gilpin Court, which Michael Paul Williams from the RTD cites in this thought-provoking column.

Gilpin Court is not Richmond’s finest neighborhood. By many metrics, the 783-unit public housing complex–the city’s largest–is in fact the worst place to live within Richmond’s boundaries. Nearly 70% of its residents live below the poverty line; statistics released earlier this year by the Richmond Redevelopment & Housing Authority indicate its average annual household income is only $8,753. A search for its recent appearances in Richmond Times-Dispatch articles reveals its 60 acres to be perhaps the most dangerous anywhere in the city.

And then there are the units themselves. Several are in obvious disrepair, their thin plastic siding somehow sheared off to expose plywood walls beneath. The most striking aesthetic features of these homes, aside from their uniformly drab and cheerless color schemes, are ubiquitous mounds of concrete, which were long ago poured over boulders and today face the street resembling nothing so much as enormous unfinished sand castles (or perhaps the Flintstone residence). Their function, or how anyone could have found them an appealing alternative to grass, remains impossible to fathom. Simply put, Gilpin Court is no place to live, and its current condition is an embarrassment to the city.

In the middle of it all, almost hidden by trash cans, is a humble tribute to its prodigiously talented and heroically dignified namesake, Charles Sidney Gilpin.

Gilpin was the youngest of 14 children, born in 1878 to a nurse and a millworker living near present-day Gilpin Court in a home that would ultimately be demolished in the 1940s to make room for Interstate 95. Gilpin’s neighborhood, Jackson Ward, was a home to thousands of freed slaves and for decades after his birth would thrive as a hub of Black commerce and entertainment. (Its most famous son, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, was born six months before Gilpin, and would enjoy greater fame and prosperity than him for most of his life, for reasons we’ll explore shortly.) Gilpin dropped out of school at 12 to apprentice for three years at the Richmond Planet–during which time he would have worked closely with another Jackson Ward luminary, John Mitchell, Jr.–before leaving town in the mid-1890s to join a minstrel show, having discovered an aptitude for performing.

The details of Gilpin’s next 20 years are a bit sketchy, but from the jobs he’s known to have held and the traveling they would have entailed emerges a portrait of unbridled ambition and self-belief. He first went to Philadelphia, where he tried to resuscitate his journalism career as a printer for the Philadelphia Standard, but quit when White employees complained about his presence. He’d find subsequent employment there as a vaudeville entertainer, but would move to Chicago after being repeatedly denied more serious dramatic roles.

There, he received his first steady work as a legitimate actor–apparently turning his back for good on the minstrel and vaudevillian circuits in which Blacks were typically typecast and demeaned (and in which “Bojangles” was now thriving)–and even moved briefly to Ontario to perform plays in front of more accepting audiences. Along the way, he supported his ambition by finding intermittent work as a barber, Pullman porter, elevator operator, and even a boxing trainer. Finally confident in his abilities as a seasoned actor, he moved to New York City in 1915 and, almost overnight, proceeded to electrify the city with his talent.

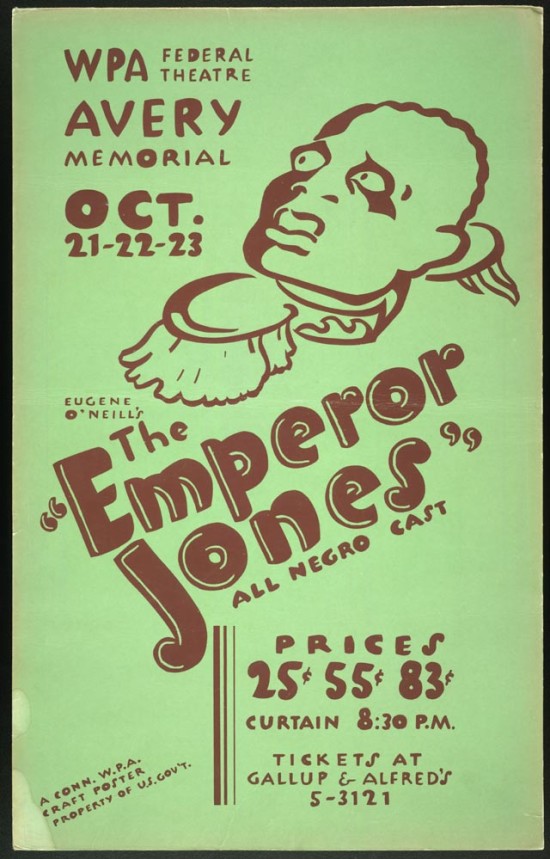

Within months, he was the lead actor of the Harlem-based Lafayette Theatre Players, performing in three well-received plays before leaving over a salary dispute. He’d soon be cast by British playwright John Drinkwater, playing former slave Rev. William Curtis in Abraham Lincoln, a heavy-handed and historically inaccurate depiction of Frederick Douglass’s influence on the 16th president. Pretty much the only thing critics agreed upon–other than the fact that the play itself was abysmal, though popular in its time–was that Gilpin’s performance was like nothing they’d seen before from a Black actor. A young, unknown playwright named Eugene O’Neill was in attendance for one of the play’s performances one evening and thought so much of Gilpin that he promptly cast him as the lead in an experimental play he’d just completed called The Emperor Jones.

It was a role that would send Gilpin to an untimely and tragic death, but not before making him the most famous and esteemed Black actor the country had ever seen.

The play, which opened on Broadway in November 1920, also made a star of O’Neill for its creative and unorthodox structure. It consisted of eight scenes, all of which but the first and last consisted of extended, artistically-demanding monologues from Gilpin’s character, Brutus Jones. The plot, which described covered the escape of Jones, a convicted Black American murderer, from prison to an unnamed Caribbean nation, where he would establish himself as ruler before dying in a rebellion–was a caustic parody of recent military intervention in Haiti. Its subversive nature attracted audiences in droves.

What audiences were treated to, by all accounts, was a singularly transcendent performance by Charles Gilpin. Within weeks of the play’s opening, it had moved to a larger venue to accommodate an ever-increasing audience. Months later, it would move again for the same reason. In 1921, he was the undisputed star of Broadway.

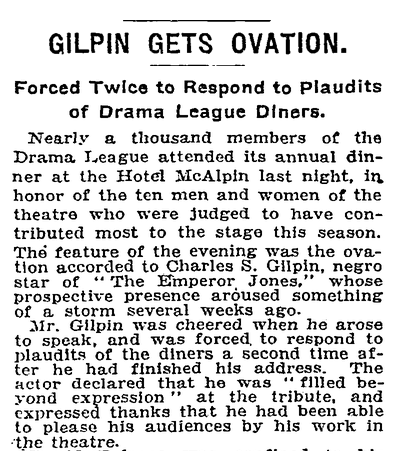

Accolades and awards came quickly. In 1921, Gilpin received the prestigious Spingarn Medal from the NAACP for exceptional contributions to his race. As context, the medal’s 1920 recipient was none other than W.E.B. DuBois, and two years later it would be awarded to George Washington Carver. Later in 1921, Gilpin became the first Black American ever to be named one of the year’s ten most significant contributors to theater by the Drama League of New York. This announcement spurred significant protests and fears of retribution, but the Drama League refused to retract its invitation to Gilpin for the awards banquet. He attended, and was the unequivocal darling of the evening:

Still later in 1921, he accepted President Warren G. Harding’s invitation to be honored in Washington. Gilpin’s unprecedented rise from Jackson Ward to the White House was complete. It would prove to be the last major public recognition he’d ever receive.

Gilpin’s downfall was triggered by his objection to the screenplay of The Emperor Jones, which used language that was–even for that relatively unenlightened era–wildly offensive. It forced him to say the word “nigger” no fewer than 35 times each performance, and to speak in O’Neill’s condescending conception of African-American dialect throughout. Here’s a representative sample, taken verbatim from the screenplay(PDF):

Lawd, I done wrong! And down heah whar dese fool bush niggers raised me up to the seat o’ de mighty, I steals all I could grab. Lawd, I done wrong! I knows it! I’se sorry! Forgive me, Lawd! Forgive dis po’ sinner!

For three years as the play enjoyed unabated success, O’Neill listened impassively to Gilpin’s concerns, and dismissed them each time. The lines and Jones’s depiction were racist, he agreed, but consistent with his dramatic intent. The rift between them deepened when Gilpin would substitute “Black babies” or “my people” for the racial epithet during performances, and by 1924 that rift had become irreparable. Gilpin, ever a man of principle, told O’Neill he would not perform his signature role for the play’s scheduled performances in London that year during what would have been his first ever trip to Europe. Unfazed, O’Neill cast an unheralded football player and aspiring lawyer named Paul Robeson in Gilpin’s part. The play enjoyed continued success abroad, and marked the first major role in what would turn out to be a remarkable career for Robeson.

That same role would turn out to be Gilpin’s last. Disillusioned with the industry he’d sought so long to enter, he moved to Cleveland in 1924 and started a small theater company offering dramatic opportunities to Black actors. He began drinking heavily and returned to more menial jobs such as operating hotel elevators to get by. In 1925, he was offered a final lifeline–the chance to make a “moving picture” in a small but steadily growing town called Hollywood, where he would play the title role in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Gilpin turned it down when he was told he’d have to perform the part in a stereotypical, demeaning manner.

Gilpin moved to New Jersey in the late 1920s, his drinking worsening each year. In 1929, he permanently lost his voice; a particularly cruel affliction for someone who’d used that same voice so eloquently only eight years earlier to make a speech of thanks to the Drama League of New York. He died, penniless, the next year, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Today, his name is not even on the cemetery website’s list of notable people buried there. Gilpin Court would open 13 years later.

If there’s a single attribute Gilpin demonstrated as brilliantly he did his talent for acting, it’s his incorruptible dignity. Each step he took toward the role that would make him a guest of honor in the White House–as well as each that drove him ever farther away from that audacious pinnacle–was forged by his uncompromising convictions. He rejected the simplest path to success for Black entertainers at the time–the kind of self-parody in which “Bojangles,” it must be said, trafficked almost exclusively–to pursue a more noble and principled one.

To have that path derailed by those very principles must have produced a pain we can’t pretend to understand. It’s heartbreaking enough to see Gilpin’s name attached today to an eyesore so unsafe and so unworthy. No, our imaginations are better served by the thought of Jackson Ward’s forgotten emperor listening with what must have been gratitude, watching with what must have been vindication, as the ballroom crowd in New York stood and began to applaud for a second time.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

Notice: Comments that are not conducive to an interesting and thoughtful conversation may be removed at the editor’s discretion.

Thank you for this — I learned something completely new about it. I never knew of Gilpin Court’s namesake at all.