The sobering, sad story of the Irish in Richmond

Not to bum you out or anything, but Grant Martin’s piece from last year about the fate of the Irish in Richmond was enthralling. Refresh your memory for St. Patrick’s Day.

They would walk up the steps wearily, with backs bent by the weight of newly forged iron, and in boots blackened by the dark river mud. They had made their way from ramshackle tenements, past mistrusting eyes and gloating jeers, all the way into the center of the doomed city. Finally, as the sunlight stretched their kneeling shadows across the coarse wooden floor of the church, Richmond’s Irish immigrants would close their eyes and begin to pray.

— ∮∮∮ —

Between 1830 and 1860, the Irish outnumbered any other immigrant group in Richmond. They were never here in particularly high numbers–records don’t indicate a local Irish population ever exceeding 2,500–but then, Richmond wasn’t an especially desirable place for immigrants to live. The kind of unskilled jobs new Americans relied upon in the Northeast were filled largely in Richmond by slaves, which resulted in deplorable working conditions and barely any pay.

But the Irish were undaunted. They’d fled their country to escape poverty, disease, and later famine; it’s not that they’d become accustomed to the unforgiving life Richmond promised–they had simply never known anything else.

Still, their decision to move here was a calculated risk. In the northern ports in which their overcrowded ships had landed–especially Boston, New York, and Baltimore–there were thriving Irish neighborhoods, with attendant familiarity and security. To move to Richmond was to place blind faith in its burgeoning mills and factories, to gamble on the city’s future in the vague hope that the fabled Irish luck would prevail.

Such faith was also reflected in their Catholicism, which they practiced fervently despite the low regard in which it was held by many in Richmond. Father Timothy O’Brien, the city’s first Catholic priest, arrived in Richmond in 1832 and immediately noted “little sympathy” among the public for his new congregation, describing those of his faith as “a degraded caste in one of the most aristocratic towns in the world.”

O’Brien realized that Richmond’s Catholics might derive some pride from a more impressive place of worship–they’d been using a humble wooden chapel on Fourth Street for their services–and began raising funds for the construction of a new church. Within two years, he’d scrounged up more than $4,000 to buy a lot, which he proudly described to the Archbishop of Baltimore as “in the genteelest part of the city and within a few yards of the western gate of the Capitol.”

What he didn’t express in that letter was the fact that the western side of the state capitol was seen as inferior; far more desirable would have been a site nearer the aristocracy in Church Hill. But there was simply no way the public would tolerate a Catholic church for low-born foreigners on the fairer side of the capitol. At the time there were no mansions along Monument Avenue (the road itself hadn’t yet been built), and so to the west of the capitol were relegated unsavory additions such as the jail, paupers’ cemeteries, and–in 1834, on the northeastern corner of 8th and Grace streets1–St. Peter’s Church, for Richmond’s Irish.

It was a lovely addition to the city. Modeled after the Church of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule in Paris, St. Peter’s boasted an elegant pedimented entrance between paired Doric columns, underneath a small but striking copper dome. It was built only of stuccoed brick–marble being a bit beyond O’Brien’s budget–but would have seemed a glittering palace to the Irish who attended its dedication on Sunday, May 25th.

“Those gathered in the new church that day were for the most part from life’s humble walks,” James Henry Bailey wrote in his history of the church, noting that the congregants were largely unable to share any money as the collection plate was passed during the service. But what they lacked materially they more than made up for in the pride they must have felt as they sat in the pews that day and gaped at the handsome windows and gleaming paint.

Beyond those walls, however, life was becoming increasingly difficult.

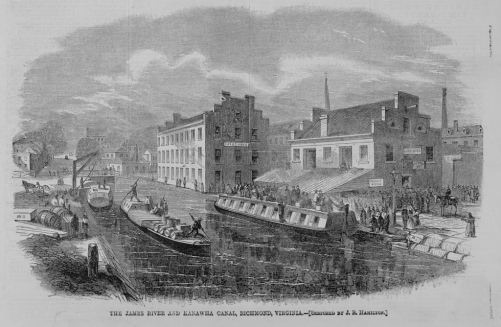

The Kanawha Canal in 1865

Most Irish men in the 1830s worked to construct the Kanawha Canal, which had been conceived a half-century earlier by George Washington as a means of transporting people and freight from Richmond to the coast. This would have been incomprehensibly grueling labor. The Irish worked alongside slaves to dig deep channels through the hard red clay, knee-deep in mud and at the mercy of the mosquitoes that would have thrived in the stagnant filth. Yellow fever, malaria, and cholera were rampant. After a particularly hot summer in 1838 during which several workers died of exhaustion, about 200 Irish immigrants fled Richmond to seek safer work in the North.

Their labor wasn’t merely dangerous–it was also completely pointless. The Kanawha Canal was never even completed, as its overseers came to the collective realization in the mid-19th century that trains could serve Washington’s purpose far more efficiently than boats. Work on the canal in Richmond was essentially abandoned by 1850. All of the workers’ effort had been for nothing.

The Irish would find new work in Richmond’s iron industry, which had been growing steadily in the 1840s and 1850s before exploding in 1860 to meet Confederate demand for munitions during the Civil War. It’s doubtful that the Irish philosophically supported the Southern cause, as they were in constant competition for work with slaves, whose emancipation would have given leverage to a labor class that had been ruthlessly subjugated for decades. Meanwhile, it would have been thankless and treacherous work amid the foundry furnaces, where injuries and deaths were not uncommon.

Many Irish were buried in Bishop’s Burial Ground, just downhill today from the Whitcomb Court housing project near the old city jail. It’s been abandoned for more than a century; the only clues that it was ever more than overgrown shrubs and trees are a pair of brick pillars, which would have once marked the entrance but are now knocked over and partly swallowed by undergrowth. There are no grave markers to be found anywhere. So after building a canal that no one needed, and producing weapons for an army that none of them supported, many of Richmond’s Irish were buried in graves that no one maintained.

How then, as the city burned during the evacuation in April 1865, could the remaining Irish have felt anything but relief? There was no longer any reason to stay in a place that had made a cruel mockery of the ambitions that had brought them there. When the war ended, nearly all of Richmond’s Irish moved to northern cities to seek better, more deserving fates than what they’d endured here.

Virtually all that’s left of their time in Richmond are several miles of an unfinished canal, a few sad tombstones in Shockoe Hill Cemetery, and one beautiful church.

— ∮∮∮ —

St. Peter’s Church spends much of its days now in shadow, dwarfed by towering apartment and office complexes built alongside it in the 20th century. Its majesty had begun to diminish as early as 1845, when a much larger and more ornate church–St. Paul’s Episcopal Church–was constructed on the other side of the street. But there’s something poetic in this architectural degradation, something both perfect and heartbreaking, something that those who were similarly devalued and humiliated could appreciate.

As the decades passed, a brilliant patina began to coat the church’s copper dome, and today its color might even bring a rare smile to those who prayed beneath it so many years ago.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 7 reader comments. Read them.