Good idea, bad idea: A Richmond Children’s Hospital

Bon Secours and VCU just walked away from the Grand Children’s Hospital Proposal of 2013. Nick Dawson tells us why this is good, and why it’s also bad.

Original — June 29, 2015

Paradoxically, there are sometimes ideas which are simultaneously good and bad at the same time. The cronut, the movie The Room, and any trip to Taco Bell are all simultaneously good and bad ideas. The same might be true of a standalone children’s hospital in Richmond. There, I said it. It’s a good idea and it might also be a bad idea. Both. At the same time.

Recently, the last two players, Bon Secours and VCU, picked up their cards and left the table. They left behind what might seem to many as a tremendous jackpot–a private philanthropy has dangled a multi-million dollar golden carrot in front of Richmond’s health system leaders. The catch? They have to all play together. It would seem like a no-brainer. Being pro kid’s health is the moral equivalent of being for lemonade on a hot day. You don’t have to even think for a second to know its something you want. So it’s a good idea, right?

Today, we’re engaged in national dialogue about health and how we deliver healthcare. While many of us have been touched by the most heroic, compassionate, and technically sophisticated parts of our health delivery system, a simple fact remains: we pay more than anyone else in the world and we don’t get what we pay for. Internationally, the United States ranks 41st among developed countries for quality. We are the highest in cost. What makes US healthcare expensive is complex. It’s also ripe for partisan and dogmatic banter. But, just like opening another Taco Bell late-night drive through, someone has to pay for the tacos or it’ll close.

The Good

Mmmmm tacos, let’s go get tacos!

There are, without doubt, many good reasons to build and support a local children’s hospital. Chief among those reasons are the unique culture of child health, the qualifications of people who specialize in caring for kids, and the emotional support of our community.

Richmond is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the country without a standalone children’s hospital. I’ve heard heart-hurting anecdotes of Richmond families making weekly trips to places like Duke, UVA, and Children’s National for years on end. They go because of the special culture and, more importantly, for the promise of high quality, specialized care. Tiny hearts require people who have practiced on them for years. Tiny tumors require special knowledge of pharmaceuticals. Physicians, nurses, and researchers at children’s hospitals have special training. Because children’s hospitals serve as epicenters of specialized care, they also tend to be safer, more advanced, and more capable settings.

Delicate families require more than just medical care. They deserve things like shared decision making, staff who know which rules to break, and the latest technologies. It’s increasingly common for children in hospital beds to video conference back into their classrooms, birthday parties, and field trips. Certainly, those are the kinds of compassionate, sophisticated services Richmond families deserve.

If you’ve ever been in a children’s hospital, you know they are special places. People who work in children’s hospitals exhibit all the best traits we want in healthcare providers. A dear friend is a former child life specialist–a role unique to children’s hospitals. In that role, he accompanied kids through the scariest parts of procedures. “If you want to kick and scream when the nurse puts the needle in, then you totally can,” he would tell frightened little patients.

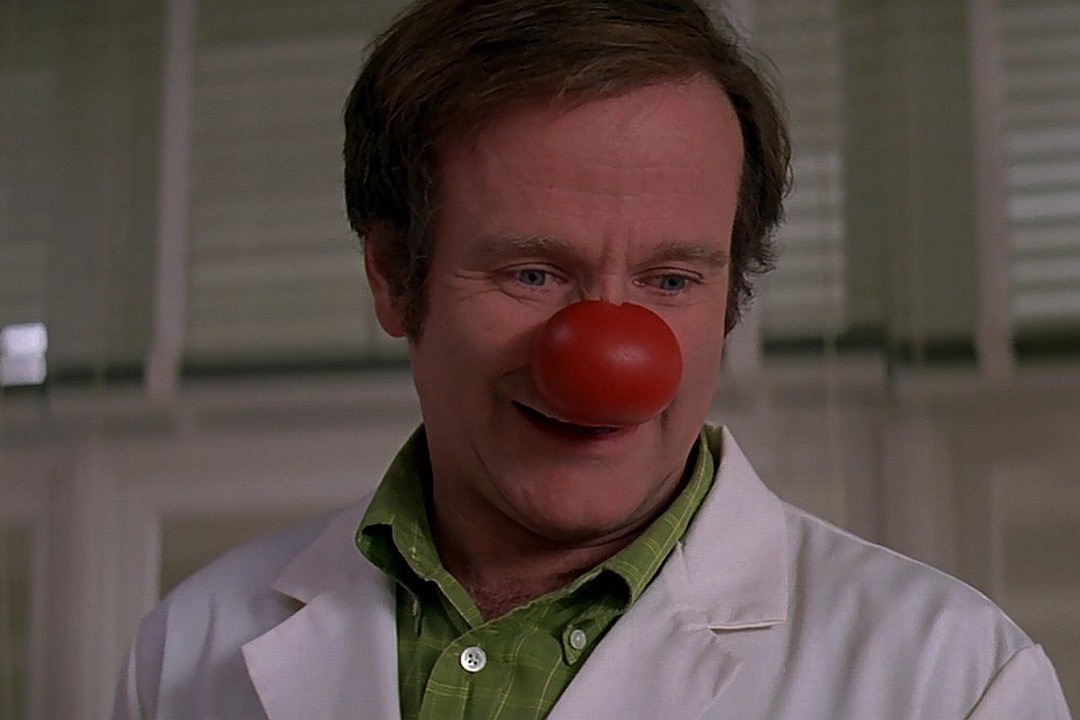

People who work in children’s hospitals fight tirelessly against every roadblock which comes between them and caring for children. They wear clown noses, sneak in puppies, and lay motionless in tiny beds holding someone a quarter of their size as chemotherapy drips slowly into their tiny arms. These are the emotionally compelling traits about children’s hospitals. They are unique and, while lamentably lacking in adult care, sacrosanct to caring for children.

The Bad

Oh dear Jeebus, why did I eat those tacos at 1:00 AM??

There are three compelling reasons by which I’ll suggest a standalone children’s hospital may not be a great idea: economics, quality, and what we might, for lack of a better term, call cooperation fatigue.

The Richmond proposal hinges on a philanthropic gift which requires local health systems to cooperate and build something independent. Most children’s hospitals are affiliated or even affixed to large academic medical centers. These are the places where researchers and doctors find breakthroughs. Because academic centers serve as beacons for advanced care, they also see high numbers of rare cases. That high volume should translate into proficiency. A recent CNN exposé revealed how an under-skilled surgeon in Florida was operating on children when he didn’t have the training and volume to do so safely. That surgeon’s results are heartbreakingly catastrophic.

A question, which remains unanswered (at least satisfactorily) is if Richmond and the surrounding community have enough health needs to support the volume to keep specialists proficiently in practice. Does the Richmond area have enough need to attract the best of the best? Every parent faced with a child with a gut-wrenching diagnosis should ask: “How many of these surgeries has this doctor done? Has the doctor at UVA or Children’s National or St. Jude done more?” In non-surgical cases, the same questioning applies: “How many kids with this rare disease has this doctor treated? Are her outcomes as good as the physician an hour or two away?”

Similarly, doctors at the top of their game have a choice about where they practice. They want to be where the cases are–where they can affect the most lives. Is their opportunity for the next breakthrough at Boston Children’s, Masonic in Minneapolis, or will a new hospital in Richmond bring them in?

The delivery of healthcare in the United States is expensive. The average primary care doctor, including pediatricians, comes out of medical school and residency with $120,000 in debt and the average earning potential of about $160,000 a year. It’s a hard life. Pediatricians see, on average, 18 patients a day or about three patients an hour. A pediatric specialist–like a heart surgeon or someone with specific knowledge of rare diseases–may make two or three times that amount. On average, you need three to five members of support staff (nurses, clinical assistants, clerical staff) for every physician. The costs start to add up quickly.

100% of healthcare costs are passed onto the public. Most costs seem to be borne by insurance companies. But, it’s important to remember that the pot of money used by insurance companies comes, mostly, from employers. Those employers withhold the cost of healthcare from the paychecks of employees. In other words, you’d get paid more if your company wasn’t buying insurance on your behalf. And, while I wouldn’t suggest this is something we should change, it’s important to see that anyone employed by a company which provides health insurance is, in fact, paying for the cost of the healthcare even if they don’t consume it.

The second largest payor of healthcare services is the government. This one is simple: our taxes fund the pool of money used to pay for healthcare services. Lastly, when those without insurance seek healthcare, it is (thankfully and mercifully) provided to them. Generally, the way hospitals cover the cost of uninsured patients is to bake that expense in to the cost of care for everyone else. Bottom line: almost all of us pay 100% of the cost of healthcare in the US. We just don’t see it as a single line item in our checkbook.

Whew! Economics interlude over! But it matters. Why? Because if we add more Taco Bell drive-throughs, someone has to pay for the tacos. Today, Richmond has about 11 licensed hospitals. Each hospital has the staff expenses outlined above. Each one, today, gets paid when sick patients come through the door. If we build another hospital and hire doctors, nurses, staff, technologists, administrators, and fundraisers, then we have cost. The golden carrot might pay for some or all of the building costs. More than likely a portion will be used to underwrite a bond for a foundation and the rest will accrue interest as the bedrock of the foundation with the sustainability of the new organization coming from patient service revenue–that’s the industry term for getting paid to take care of sick people.

There are, nonetheless, some new emerging operating models for hospitals. The most prominent is the idea of an accountable care organization or ACO. An ACO gets paid, or most often pays itself, when the health of a given population is maintained or increases. That’s a great model for a fully integrated health system. But it’s a bit challenging when you care for a specialized population like children. So a new children’s hospital would likely have to contract with one or more ACOs to be a for-contract provider for the children covered by those plans. Needless to say, that further challenges the expensive operating model of a freestanding children’s hospital.

And maybe it’s not about the tacos at all.

So…?

Why are we even up at 1:00 AM?

If you tell me tomorrow that Richmond will get a children’s hospital, I’ll likely be happy. I’ll continue to believe it is both a good idea and a bad idea at the same time. But by and large, the special culture of children’s hospitals probably deposit more emotionally into a community than they withdraw. But there’s still a major part of this idea which would remain a concern for me.

What does it say about the state of healthcare when altruism and the care of sick kids cannot cut through bureaucratic red tape, finances, and organizational egos? Even if the Richmond-area health systems find a way to cooperate, will they really have their hearts in it?

— ∮∮∮ —

Nick Dawson, MHA spends his days trying to make healthcare better, more equitable and available to everyone. He is the Executive Director of the Johns Hopkins Sibley Innovation Hub, a founding board member of Stanford Medicine X and the current president of the Society for Participatory Medicine. Nick credits his many years as an employee of Bon Secours with showing him how healthcare can be compassionate, mission-driven and community-oriented.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 3 reader comments. Read them.