Virginia Holocaust Museum continues to show just how far hate and violence can go

Both the Auschwitz/Oswiecim exhibit and director Waitman Beorn are new to the Virginia Holocaust Museum this year, and both will help strengthen the museum’s mission.

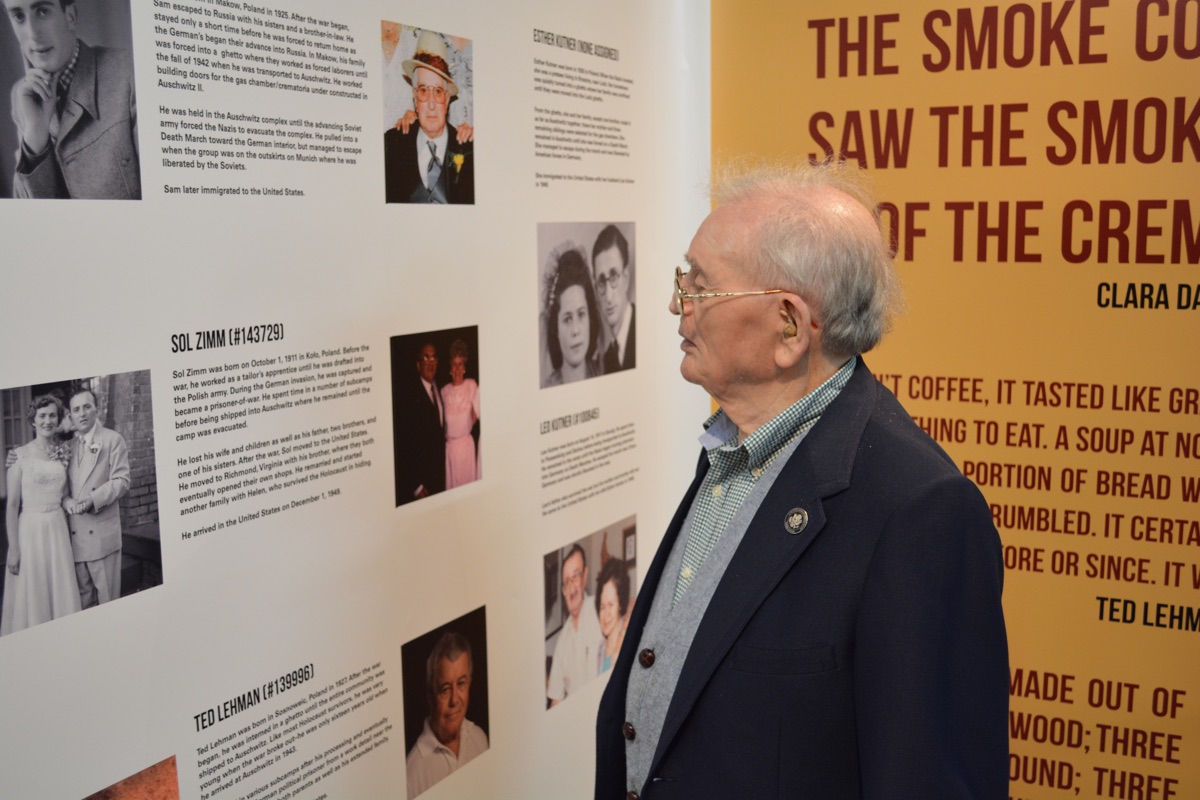

Above: Local Survivor Alan Zimm examines the survivor panel in the Auschwitz exhibit. Alan’s brother, Sol, is one of the featured Auschwitz Survivors whose story is told throughout the exhibit.

The Virginia Holocaust Museum welcomes two new additions this year–the temporary Auschwitz/Oswiecim exhibit and new director Waitman Beorn.

Both have had a chance to settle into their respective roles in the weeks and months since they’ve moved into the building. The former will be the first that the museum has sent out into the world as a traveling exhibit, and the latter is making his first foray into museum administration from the world of academia, where he specialized in genocidal studies.

So of course it’ll never be a cheerful place, but hopes are high at the VHM that everything will continue to look up for this beautiful, haunting space tucked right up against the Canal Wall in a neighborhood that had its own struggles with white supremacism and racial violence a century before World War II began.

Why Auschwitz and Why Now?

While the name “Auschwitz” is arguably the most recognizable of all of the names of the Nazi labor and/or extermination camps, most of our photographs come from Dachau and Buchenwald, where U.S. troops did the liberating. Auschwitz, much closer to the Eastern front, was liberated by Russian troops instead. This year marks the 70th anniversary of that event.

From the museum’s website:

Auschwitz I: illustrates the inhumanities developed by the SS and their inmate trustees for the persecution of political and religious prisoners, and the codified sadistic brutalities inflicted on the non-Jewish ethnic and national victims brought to Auschwitz from all over Europe.

Auschwitz II: was the extermination camp at the nearby crossroads at Birkenau, which was built in stages of continuous expansion from March 1941 until September 1944 to carry out the rationally planned, systematic mass murder of Jews and other racial enemies on a truly industrialized scale;

Auschwitz III: represents the brutalities of exploitation in slave labor and industrial violence in the Nazi cosmos of persecution and murder were nowhere more terrible than at Auschwitz III, or Monowitz, the site of the gigantic synthetic rubber production plant that was the joint venture of I.G. Farben and the SS — at the time to be the largest partnership between German big business and Himmler’s SS empire.

As World War II ground on and the Holocaust proceeded relentlessly Auschwitz came to serve the SS as the centralized hub, and the experimental crossroads for each phase and virtually every aspect of the Holocaust. In each of the three main Auschwitz camps virtually every inhumanity inflicted by the SS upon its victims was introduced, refined, and expanded into a lethal calculus that transformed Auschwitz into the single most important site of the European Nazi Holocaust. In its most expanded form, at some point in 1944, the inmate population in the three main camps combined exceeded 200,000, making Auschwitz into a Nazi city of suffering, and a place where, along with the crammed death traps that were the ghettos in Warsaw and Lodz, the Holocaust exacted its greatest toll.

Tim Hensley, who spearheaded the curation of the Auschwitz/Oswiecim exhibit, was able to get his hands on some photos from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C. But he also realized that the personal stories of the camp’s survivors who currently live in Richmond could be just as–if not more–powerful.

“We decided [the exhibit] could have a simplistic narrative framework and describe [the camp’s] importance in the Nazi system,” says Hensley. “Also, we had to talk about how Auschwitz was this unique hybrid camp, both killing center and concentration camp with slave labor.”

Of the 30 or so local Holocaust survivors still living in Richmond (the number used to be around 100), about a third of them spent time in Auschwitz. The museum had already recorded some oral histories and began to comb back through them and pull out the individual narratives. Fortified with photos, the exhibit asks you to really dig into the personal experiences of these individuals. The stories are disturbing, and they’re very real, which is sometimes hard to remember the more the Holocaust is depicted in fiction. And, of course, the fewer survivors exist.

Perhaps one of the greatest and most bizarre windows into life at Auschwitz, as viewed from the vantage point of privilege, is the so-called “Lili Meier Album,” which contains 193 photographs taken by an unidentified SS officer. (I highly recommend clicking the link for the nearly incredible story of how the album got its nickname.)

Auschwitz Survivor Clara Daniels speaks at the exhibit opening. All photos courtesy of the Virginia Holocaust Museum.

The album belongs to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Israel, with whom the VHM was lucky enough to access through the national museum. Not only are the photographs done by a talented photographer, and not only do the pictures provide a rare perspective, but it adds another aspect of despair to the entire situation–a reminder that there were human being just looking on, taking pictures, going home to their families at night, living life. It’s crazy.

“To my knowledge it is the only chronicle of the process itself–the train pulling up, the officers going through men and women, the prisoners being split up and going to work details, what happened during work detail, and the entire process of those that were selected for gassing (in this case it was gas crematorium #4),” explains Hensley. “They’re vivid and stark, taken by a guy who’s clearly got a vantage point that nobody else has.”

The opening of the exhibit on April 19th brought survivors together to face the museum’s representation of their personal stories. With 19 seven-foot panels of text and photographs, a past they were grateful to leave behind is suddenly there, ready to seep into our nightmares.

But they’ll know that it’s all for a good cause. The Virginia Holocaust Museum is free for a reason–they believe that everyone should have unfettered access to these horrific images, artifacts, and stories. “Part of our job is to show that the Holocaust is relevant today,” says Waitman Beorn. “We still experience racism, sexism, homophobia, and whatever else. Holocaust and genocide are extreme outcomes of these beliefs if they’re left unchecked.

“The Holocaust didn’t happen overnight. It took twelve years of HItler and his government actively checking in with the German people to see if they were crossing a line [with them]. And they kept finding out that they never did on their path to radicalization.”

Local Survivor Helen Zimm examines the survivor panel in our Auschwitz exhibit. Helen’s late husband, Sol, is one of the featured Auschwitz Survivors whose story is told throughout the exhibit.

A “cautionary tale” is too cute-sounding of a phrase. “Grisly warning” is better. Some Holocaust museums shy away from showing a lot of the most gruesome images lest they be viewed as gratuitous. The VHC, for the most part, resides on the other side of the fence.

“My point of view is that, properly framed and introduced, it does a disservice to the Holocaust to leave out the horror,” Beorn explains. “There are pictures you can choose and pictures you can not choose. You can get some absolutely awful pictures, but you can also get some slightly awful pictures. The words of both the perpetrators and the victims can be sometimes equally or more awful than those pictures…The question is always, does this desensitize the viewer or does it impact the viewer.”

Voyeurism is certainly a concern–and Beorn came across his share of it while a professor of genocidal studies at University of Nebraska Omaha. Students would have a fascination with learning about the Nazis themselves, and Beorn would find himself steering them towards studying the victims instead. Now, he helps to keep the museum from providing a voyeuristic outlet while still maintaining the real horror of the experience so that we as a global population can make an informed vow never to let this happen again. It’s a tricky job, he and Hensley agree.

“Every image you see, we have thought through,” says Beorn.

As has been so tragically and dramatically demonstrated within just this past week, senseless acts of racism-fueled violence have yet to die out, which is why museums like this one are so necessary. A large portion of the VHM’s visitorship is students, who desperately need to realize that the whole thing wasn’t just the plot of many successful movies. Real people did this to other real people, and they can do it again if we’re not vigilant.

“Because all these ‘-isms’ exist in the Holocaust, it’s easy for teachers to make those connections–the raft of anti-Jewish laws between 1933-1939 with Jim Crow laws…Not only can we speak of the community that we’re trying to represent, we can also provide tie-ins to something that is probably being intentionally avoided on some political or racial level,” Beorn says.

Until the day that these reminders are no longer needed, the Virginia Holocaust Museum will be free to the public.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are no reader comments. Add yours.