10 x 10 Week 3: Performing Statistics

Mark Strandquist’s Performing Statistics tackles criminal justice reform in a way that involves, well, everyone.

Every time Mark Strandquist’s name comes up, it’s in relation to some sort of art that’s both incredibly cool and socially impactful1.

With Strandquist at the helm of Week 3 of 1708’s 10 x 10 Project, Performing Statistics, the issue in the limelight is criminal justice.

His VCU undergrad work on a project called “Windows to Prison” put him in direct contact with incarcerated individuals through creative writing workshops. He would ask, “If you could have a window in your cell to a place in your past, what would it look out to?”

“And then I’d go to that exact location and photograph it for them,” Strandquist says, like it’s no big deal.

The messed-up numbers surrounding the incarcerated in our town, our state, and our country have haunted him since–and the very idea that each of those numbers is a human being is often lost on the majority of the population.

As part of the Windows From Prison workshop with TJHS, prisoners came up for “performances” for the workshop participants to do at their requested location. This went from throwing a crab leg into a lake for a woman’s deceased father, to long moments of silence, to here, where the participants were asked to look at a home that had been a site of pain for the incarcerated woman, spin around and around, then walk and never look back. Thomas Jefferson HS students who helped create the photos also drew illustrations as a form of documentation. They were given to the incarcerated participants along with their image.

Windows to Prison expanded nationally, and after a couple of years working with VCU’s Open Minds program, Strandquist was starting to have more ideas. “We came up with this concept of how prison reform would differ if it were led by those that were incarcerated. What if we could use art as a way to show what people who are most affected by these issues think?”

Performing Statistics deals primarily with youth, who leave their detention facility to work with lawyers (they’ve engaged Legal Aid for this part), designers, artists, and trauma care specialists to create art, get advice, and spur media campaigns. “Basically, the goal is to spend the summer creating this media and then tour with Legal Aid around the state to really promote awareness,” Strandquist says. “The teens are really creating media to support criminal justice reform.”

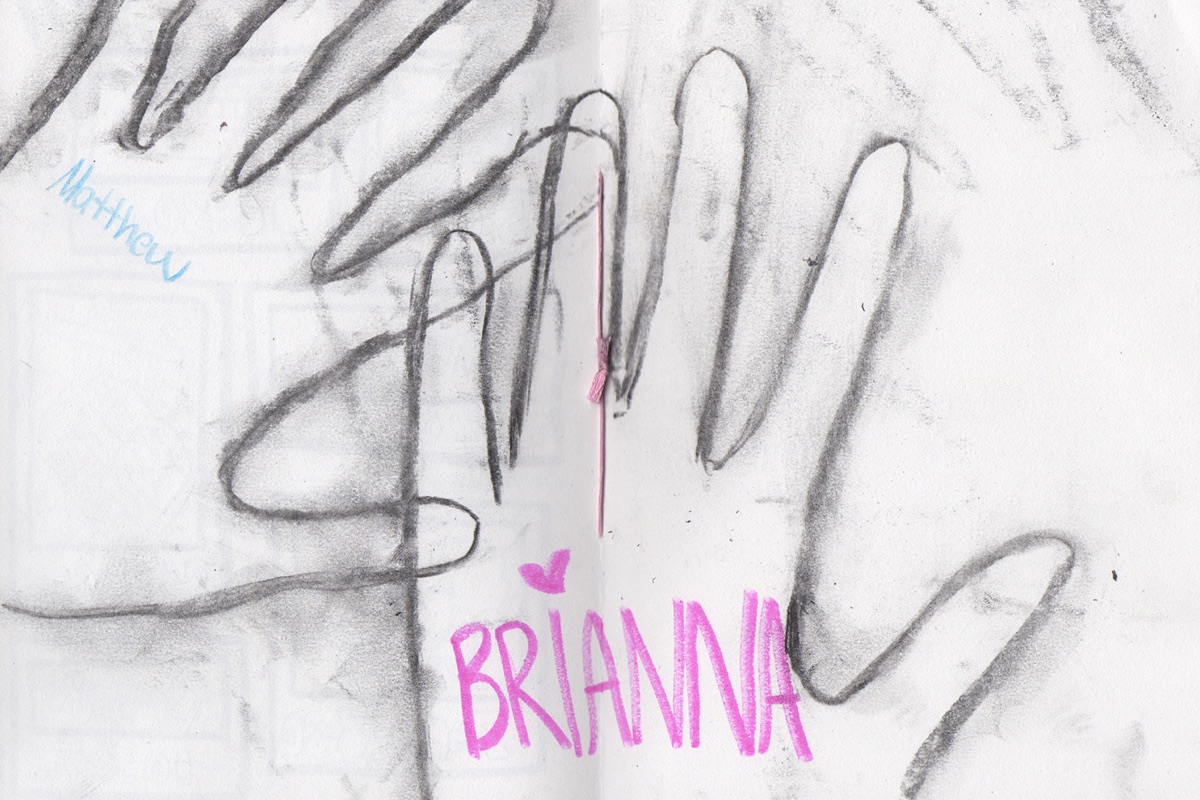

Strandquist shows me a journal kept by a Thomas Jefferson High student and an incarcerated youth–the two exchanged back and forth, writing about themselves, getting to know each other, and eventually each drawing a handprint that overlapped. “It really brings all these people together to bring humanistic entry points into complicated and systemic issues,” he says. “Art gives them a vehicle for sharing their experience and histories, but also for amplifying those voices.” In other words, if you don’t know how to say how you feel, maybe you can express it visually.

Scan from one of the collaborative journals that went back and forth between art students at Thomas Jefferson High School and incarcerated men and women at Richmond City Justice Center. The book exchange ended with each author charcoaling the outside of one of their hands symbolizing the connection the book has made across boundaries and beyond walls.

Art 180 is hosting the ongoing programming, where a different artist comes every week, identified by Strandquist, accompanied by lawyers from Legal Aid to help everyone frame their issues most impactfully.

“Art can transform exclusionary legal language into really humanistic language too. And we need the lawyers to make our work be more than symbolic and more than just representational of the experience of being incarcerated.”

As part of the exhibit, artist Mark Strandquist organized a Windows From Prison workshop where students, professional photographers, VCU art ed students and many others came together to create photographs requested by incarcerated men and women. The participants went to the exact location each prisoner requested, made the image, and then printed the photo for each incarcerated participant.

Because Strandquist isn’t really into just revealing what life inside is like–there are plenty of people doing that. He wants to know what those who are incarcerated want to express, and what that means about our own criminal justice system.

“Personally, I think it’s a human rights issue of my generation,” says Strandquist when I ask him what keeps drawing him back to criminal justice reform. “I would say that any issue that I’m frustrated by or passionate about can be found in the criminal justice system, whether it’s racism, socioeconomic inequality, food justice, trauma, informed care–it’s all made exponentially worse by the criminal justice system. So by engaging with it allows me to feel like i’m engaging with these issues as well.

“When you hear these numbers, like that there are 2.3 million behind bars, that’s more than the entire population of France! It’s a social crisis and a social emergency, and I think artists have an important role.”

Art 180 teens working to create their human scale model of the school to prison pipeline.

All week, you can head to 1708 and view some alarming visually represented numbers, including a life-sized timeline of cradle-to-cell existence by the amazing teens at Art 180, a cell gallery, some photographs, some art, and a bunch of special programming, beginning tonight.

- Tuesday, June 16th • 6:00 PM, Public Announcement and Panel with Project Partners

- Wednesday, June 17th • 12:00 PM, Windows From Prison workshop (led by Mark Strandquist)

- Wednesday, June 17th • 6:00 PM, Fierce Love: Style and Words as Revolution (led by Open Minds and Sanctuary RVA)

- Thursday, June 18th, • 3:00 PM, Ending the School to Prison Pipeline: Strategies for Youth Navigating the School & Juvenile Justice Systems (led by Legal Aid Justice Center)

- Thursday, June 18th • 6:00 PM, Youth roundtable with Richmond City Police Dept.

- Friday, June 19th • 6:00 PM, Hallways to Handcuffs: Conversations about the criminalization of our youth (led by ART 180 Teen Leaders)

- Please see The People’s Library. ↩

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

Notice: Comments that are not conducive to an interesting and thoughtful conversation may be removed at the editor’s discretion.