Civil War: The winter of desertion

They were committed to their Cause. They were angry at the other half of their nation. They were willing to fight to the death! Until a winter of not being paid, clothed, fed, or sheltered made them all peace out. And with dang good reason.

For today’s column, I thought it would be good to pause and remind everyone where we are. It’s January of 1865 and the siege of Petersburg, which started in July of 1864, is now in its seventh month, with the two armies more or less staring at each other across deeply-dug trench lines. On the Union side, a war machine the likes of which the nation has never seen is steadily resupplying, reinforcing, and strengthening the army of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. On the Confederate side, Gen. Robert E. Lee has been stuck in a defensive position he never wanted to be in, with a smaller army, supply and ration shortages, and a steadily decreasing number of escape/resupply routes.

To top it all off, it’s fucking winter. And it’s been pretty cold and miserable.

So, imagine for a moment that you are a Confederate soldier on the front lines. Your rations have been reduced significantly for a few months, you haven’t been paid in awhile, and news from back home and camp rumors all suggest that the Confederacy is in trouble. Unless you are particularly honorable and duty-bound, you might entertain the thought of finding a way to get the hell out of Petersburg and back to your home. And, in the winter of 1864-1865, in record numbers, that’s what a lot of soldiers did.

The issue of desertion was so prevalent that winter that Robert E. Lee regularly addressed it with the War Department back in Richmond:

I have the honor to call your attention to the alarming frequency of desertions from this army. I have endeavored to ascertain the causes, and I think that the insufficiency of food, and non-payment of the troops, have most to do with the dissatisfaction. There is suffering for want of food. The ration is too small for men who have to undergo so much exposure and labor.

Over the next several weeks, Lee would remain focused on trying to address the issue of desertion within his army. In addition to trying to secure more food and supplies for his soldiers, he also entertained some outside the box ideas. He wrote to Jefferson Davis to suggest a 30-day grace period for all deserters to return to their units without punishment, in an attempt to repair some of the damage that had been done.

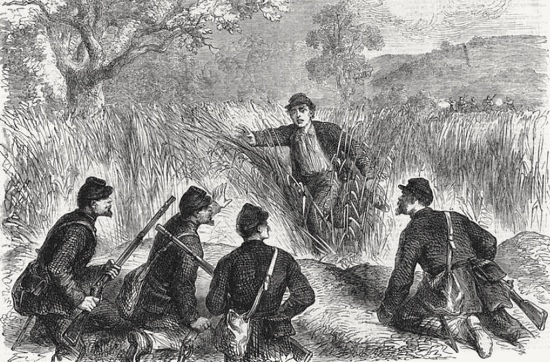

In the first few months of 1865, thousands of rebel soldiers crossed the picket lines to desert, either to return home or surrender to Federal troops (often in hopes of better rations as a prisoner). Some reports indicated as many as one hundred Confederates deserted per day. On the Union breastworks, soldiers built a wooden arch entryway facing the Confederate lines. The arch was lit each night with lanterns to reveal a message written upon it: “While the lamp holds out to burn, the vilest rebel may return.” (Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, Vol. 7) This simple invitation to cross the lines, a bit of psychological warfare, had its desired effect.

Now that we’ve painted a pretty dire picture of the Confederate army’s situation, it may surprise you to hear that the Union army had a desertion problem as well. While not as significant in number as the Confederates, thousands of Union soldiers also crossed the lines to escape duty in the army. While Confederate desertions were driven by hunger and demoralization, it appears Union desertions were more a result of the many fresh recruits brought in to reinforce the Union army during the last year of the war. Many of these soldiers were not battle-tested whatsoever, joining the army for the large cash payment upon signing up and then quickly deciding army life was not to their liking. While Lee and the Confederate government were weighing the idea of a lenient approach to woo back deserted soldiers, the Union army was decidedly more strict in this matter. Hangings and shootings of Union deserters were a regular occurrence during the winter. “We are treated to a hanging exhibition every Friday,” wrote a soldier, “and the men have grown to enjoy the spectacle. We lose all human feelings towards such dastards and traitors.” (Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel. pg. 295)

So, we’ve got a demoralized Confederate army hemorrhaging soldiers, unable to supply and feed itself, and a war that is about to resume hostilities in the spring. It kinda feels like the wheels are about to come off the Confederacy, right? Adding to that is the fact that Lee is about to get hit with another blow when, thinking there was still several more weeks left of quiet winter, a surprise period of warmer weather in February gives Grant a window in which to launch his first attack of 1865.

The last few months of the war are upon us–and it only gets crazier from here! Stay tuned.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There are 3 reader comments. Read them.