Civil War: The fight for Northside

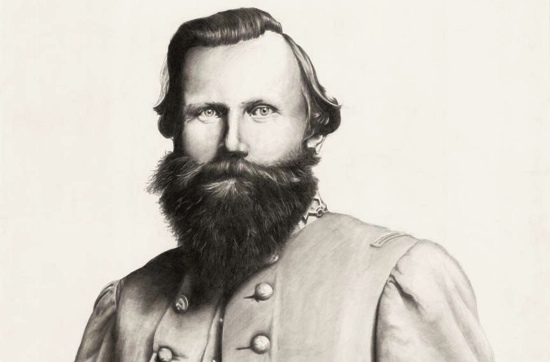

150 years ago today, General J.E.B. Stuart died in downtown Richmond.

After an intense fight at the Battle of the Wilderness, Union General Ulysses S. Grant headed south toward Richmond in an attempt to wedge his army between Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the capital city, cutting off his supply lines. Anticipating this move, Lee quickly headed southeast and positioned himself at a place called Spotsylvania Court House. There, the Union and Confederate armies would collide repeatedly for two weeks.

While this battle dragged on, another smaller cavalry force, led by Union Gen. Philip Sheridan headed south to find Confederate Gen. J.E.B. Stuart and engage him in battle–something Sheridan had been itching to do for some time.

In the Union army, cavalry was typically used to screen troop movements and perform reconnaissance, but Sheridan longed to take his cavalry out on independent missions. He believed that, if given the chance, he could eliminate J.E.B. Stuart and threaten Richmond without being encumbered by the rest of the army. When he proposed this action, Meade initially rejected it, but Grant basically said, “OK, let’s see what you can do.”

So Sheridan set out south to find Stuart on May 9th with 10,000 troops. He made no effort to disguise his movements, attacking a supply depot and railroad lines along the way, so it was only a matter of time before Stuart’s cavalry showed up to intercept him on his way south. That fateful meeting would take place on May 11th at a place called Yellow Tavern. Today, that spot is located just north of the city near Virginia Center Commons Mall. Stuart and Sheridan battled it out for the afternoon, but Sheridan’s cavalry force outnumbered Stuart’s nearly two to one, and reinforcements were too far away to reach the Confederates in time.

In order to shore up his lines, Stuart rode along the front and encouraged his men to push forward. As they drove back a Union assault, a retreating Union sharpshooter named John Huff took an opportunity to fire at Stuart with his pistol, hitting him with a mortal bullet wound in the side. When one of his aides reached him, he said quietly “I’m afraid they’ve killed me.” As Stuart was pulled off the field, Gen. Fitzhugh Lee (Robert E. Lee’s nephew) took command of the Confederates and fought off Sheridan for another hour before they were forced to retreat.

With Stuart out of commission and his army in retreat, Sheridan pushed on south down a road called Brook Turnpike (better known today as Brook Road). On May 12th, he easily passed through Richmond’s outer-most defenses which were unmanned at the time and found himself at the modern day intersection of Brook Road and Azalea Avenue. The defenses he saw ahead of him were fully manned, and he was soon attacked from the rear by elements of Stuart’s cavalry led by Col. James B. Gordon. A fight quickly ensued and Sheridan made the decision to escape to safety rather than continue forward to Richmond. He headed east to cross the Chickahominy River and joined up with a force commanded by Gen. Benjamin Butler.

While Richmond’s inner defenses to the north are gone today and replaced by residential streets, there’s a plaque marking their original location just south of the intersection of Brook and Laburnum. Remnants of Richmond’s outer defenses can still be seen in a rather unexpected place: the Martin’s grocery store parking lot just off of Brook Road.

Meanwhile, back in Richmond, J.E.B. Stuart lay dying in the house of his brother-in-law, Dr. Charles Brewer. The house was located on W. Grace Street between Madison and Jefferson Streets, right near where the police station stands today. Throughout the day of May 12th he saw numerous visitors at the Brewer house including President Jefferson Davis. But most of all, he longed to see his wife Flora who was away in the countryside and hastily summoned to the house. Stuart’s final hours were documented in the Southern Historical Society Papers:

During the evening he asked Dr. Brewer how long he thought he could live, and whether it was possible for him to survive through the night. The Doctor, knowing he did not desire to be buoyed by false hopes, told him frankly that death, that last enemy, was rapidly approaching. The General nodded and said, “I am resigned if it be God’s will; but I would like to see my wife. But God’s will be done.” Several times he roused up and asked if she had come.

To the Doctor, who sat holding his wrist and counting the fleeting, weakening pulse, he remarked, “Doctor, I suppose I am going fast now. It will soon be over. But God’s will be done. I hope I have fulfilled my destiny to my country and my duty to God.”

At half past seven o’clock it was evident to the physicians that death was setting its clammy seal upon the brave, open brow of the General, and told him so; asked if he had any last messages to give. The General, with a mind perfectly clear and possessed, then made dispositions of his staff and personal effects. To Mrs. General R.E. Lee he directed that his golden spurs be given as a dying memento of his love and esteem of her husband. To his staff officers he gave his horses. So particular was he in small things, even in the dying hour, that he emphatically exhibited and illustrated the ruling passion strong in death. To one of his staff, who was a heavy built man, he said, “You had better take the larger horse; he will carry you better.” Other mementoes he disposed of in a similar manner. To his young son he left his glorious sword.

His worldly matters closed, the eternal interest of his soul engaged his mind. Turning to the Rev. Mr. Peterkin, of the Episcopal Church, and of which he was an exemplary member, he asked him to sing the hymn commencing —

“Rock of ages cleft for me, Let me hide myself in thee,” he joining in with all the voice his strength would permit. He then joined in prayer with the ministers. To the Doctor he again said, “I am going fast now; I am resigned; God’s will done.”

Thus died General J.E.B. Stuart.

Sadly, his wife Flora arrived a few hours too late to say goodbye to her fallen husband while he was still alive. She would wear black in mourning for the remainder of her life and would never remarried. When news of his death reached Lee in Spotsylvania, he remarked “I can scarcely think of him without weeping.” Stuart’s funeral, held the following day on May 13th, was a quiet affair without music or marching soldiers to accompany the casket on its path to Hollywood Cemetery. With Richmond still in danger from Sheridan’s cavalry, the City Battalion was unable to spare any soldiers. For the flamboyant and larger-than-life cavalry commander, it seems an ill-fitting end for someone who would have appreciated the pomp and circumstance of a grand state funeral.

These days, Stuart can be found watching over Monument Avenue along with the other Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson. If you’re interested in a slightly lesser-known monument to Stuart, head north on Brook Road just after it intersects with I-295 and you’ll see signs leading you to a monument at the spot where he was mortally wounded. Tucked away in a quiet residential street, the monument stands nearly forgotten aside from the occasional trinkets and flags left by past visitors.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.