Civil War: A high-stakes election

One of the turning points of the war: November 8th, 1864.

One of the benefits of looking back on the Civil War 150 years after the fact, is that we can see with 20/20 hindsight all those critical moments–decisions made in the fog of war, battles that could have gone one way or another–that had a pendulum-swinging effect on the war. November 8th was certainly one of those moments. On November 8th, 1864, Abraham Lincoln was re-elected for a second term as president to finish out the war he had started.

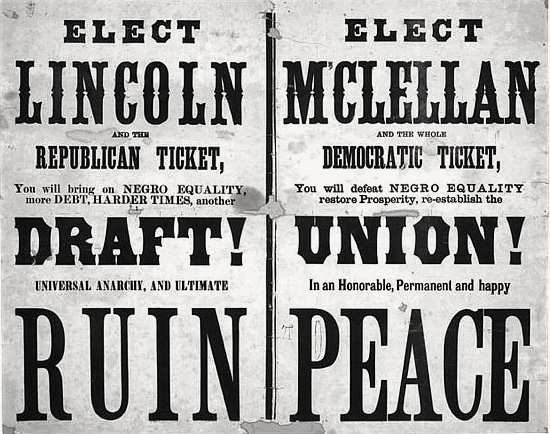

In the months leading up to the election, Lincoln had several reasons to doubt he would win. The last president to be re-elected was Andrew Jackson in 1832, the stalemate in the trenches outside Petersburg was entering its fifth month, and a general war fatigue had set in among the population. At the outset of the election, Lincoln barely had a consensus within his own party, with several of his fellow Republicans trying to push a less moderate nominee while still others called for impeachment. His Democrat opponent was a blast from the past: General George B. McClellan, former head of the Army of the Potomac, whom Lincoln removed from office after his over-cautiousness cost them victory during the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. McClellan was willing to negotiate a peace with the Confederacy to end the war and railed against Lincoln on many issues, particularly emancipation.

Confederate soldiers in the trenches of Petersburg waited for the outcome of the election with much anticipation. To them, four more years of Lincoln ensured four more years of war. McClellan represented a chance for peace and many wrote home encouraged by his chances. A private stationed outside Petersburg wrote back to his sister in North Carolina:

I heare a heap of talk heare about the army mistress [armistice] not to fight no more for a surten length of time. I hope they will have and army mistress [armistice], and it is hope they will come to some conclusion for an honorable peace. I am tired of this war. Power, J. Tracy. _Lee’s Miserables_

Others were not so optimistic, despite what they’d heard about McClellan and the Democratic platform as the “Peace Party.” One South Carolina soldier remarked that “the only peace party upon whom we can rely for any good to ourselves are our Armies in the field.”

Meanwhile, back in Washington, Lincoln himself doubted his chances just as much as anyone. He remarked to a fellow Republican, “You think I don’t know I am going to be beaten, but I do, and unless some great change takes place, beaten badly.” He even wrote a memorandum, outlining his thoughts on what should happen if he were to lose the office, and sealed it–to be opened in November.

Don’t let Lincoln’s pessimism fool you, though. Despite his doubts and fears, he was making every effort to shore up his support and increase his chances for victory. He even created a process to ensure that soldiers on the field of battle (some of his most ardent supporters) could vote, despite being far from home. Lincoln launched the first major effort to instate absentee balloting in 1864. While it was seen as a somewhat controversial move at the time, it’s now seen as a vital part of our electoral process.

If you follow politics today, pundits often talk about an “October surprise”–that unforeseen event that happens just prior to an election that can drastically shift the fortunes of the candidates. For Lincoln, his “October surprise” came a month early in the form of a telegram from General William Tecumseh Sherman. “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.” Sherman’s infamous “march to the sea”, had succeeded in toppling one of the Confederacy’s biggest cities. The fall of Atlanta, seen by the public as a major turning point, shifted support back to Lincoln, who was now fighting a “winnable” war again.

And, as it would turn out, Lincoln’s efforts to get out the vote to Union soldiers on the field played a huge role as well. When all the absentee ballots were counted on November 8th, 78% of Union soldiers who voted placed their vote for Lincoln. He ended up winning the popular vote by 55%–a margin of only 400,000 votes. Lincoln now had the mandate to finish the war on his terms: only through unconditional Confederate surrender and without compromising on emancipation.

It doesn’t take much to imagine the negative impact of a McClellan presidency in 1864. Our country as we know it today could have been completely different. A peace agreement surely would have extended the existence of the Confederacy and continued the practice of slavery for years to come, possibly even leading to the repeal of the Emancipation Proclamation. So when I say that November 8th, 1864 was one of those pendulum-swinging critical moments of the war, you can see why.

In the memorandum he composed and sealed in the event that he did not win reelection, Lincoln wrote that he would attempt to pour as many resources as he could into the war effort in the few months after the election. If he was forced to leave the office, he would make every attempt to finish the war before McClellan’s inauguration. In the end, he came remarkably close, with the final days of the war taking place only a month after the inauguration.

Fortunately, with his presidential victory secured, he was able to pursue the final months of the war without having to worry about the actions of his successor.

-

Recommend this

on Facebook -

Report an error

-

Subscribe to our

Weekly Digest

There is 1 reader comment. Read it.